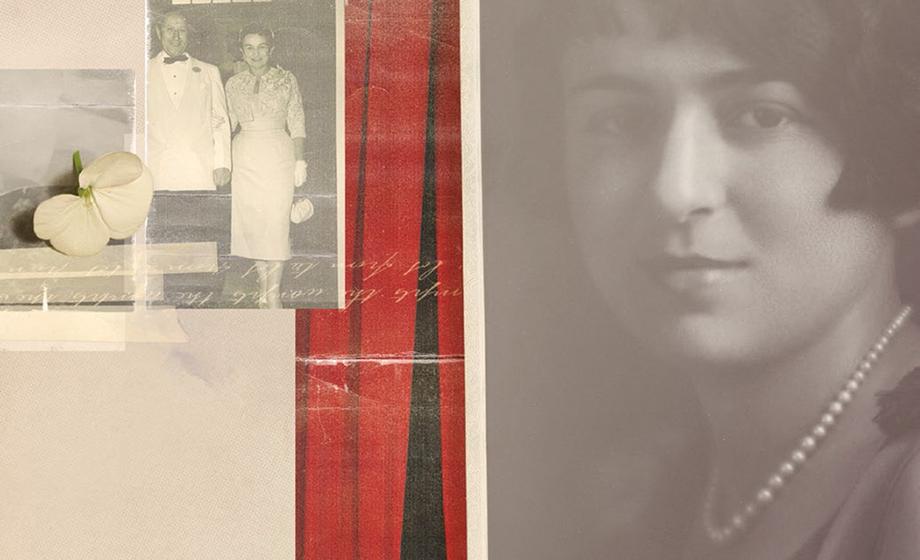

Goldie Michelson’s history is our history

Above all else, Goldie Michelson relished a good walk.

She walked for health. She walked to think. She walked because she hated driving. One of her greatest joys, she once recalled, was the day she sold her car.

Her devotion to forward momentum never ceased. Well into her 90s, she was walking a few miles a day in her Worcester neighborhood. In the winter, she’d march up and down the stairs of her house. And when she grew too old to climb, she crossed the floor of her living room every hour or so with the assistance of a health aide.

Goldie only stopped walking when her legs insisted, “No more.” She died on July 8, 2016, at the age of 113 years and 335 days, the oldest person in the United States, the oldest Jew in the world, and surely the oldest Clark University graduate (M.A. ’36) there has ever been. Her life spanned all but 15 years of this institution’s 129-year history.

Yet while her body has been stilled, her story continues to evolve through the generous donations she made to Clark and in the many lives that intersected with hers. For these reasons, it’s worth taking one more walk with Goldie.

⇔

Clark in 1936.

Two-year-old Goldie Corash, her mother and two brothers emigrated from Russia’s Pale of Settlement to Worcester in 1904. They joined her father, Max Corash, who’d come to the U.S. six months earlier and opened a dry goods store in the city’s Water Street section, home to a thriving Jewish immigrant community.

The Corashes lived a comfortable and relatively privileged life, thanks to their work ethic. Goldie would acknowledge her good fortune, and its attendant responsibilities, in an interview published in the 2001 Worcester Foundation for Biomedical Research annual report, in which she recalled her father’s words: “He always said that this country had been so good to him; that those of us who are lucky should look out for those who have less.”

Goldie threw herself into the theater while attending Worcester’s schools, whether it was acting, finding costumes or working the lights. Her zest for people was noted early. Goldie’s senior-year profile in Worcester’s Classical High School 1919 yearbook described “little Goldfish” as “witty, clever and jolly, and so agreeable that wherever she goes she has a host of friends. … She has an inexhaustible store of jokes which could make the coldest person laugh.”

Her yearbook from the Women’s College (later Pembroke College) of Brown University, where she earned her bachelor’s degree in sociology in 1924, depicted a similar persona: “Not a blonde, as her name would suggest, nor from New York, as her style suggests, nor does she vamp professors as her eyes suggest. In more ways than one, Goldie suggests one thing, and does another. Could anyone else dance so unceasingly, step out so often, yet be the pride of her professors’ hearts? No, say we emphatically. Goldie’s ambition lies in the field of social service work.”

After graduation, she returned to Worcester and secured a $25-a-week job at Worcester State Hospital. When she informed her father about her newfound employment, he took $25 from his pocket and told Goldie that he would pay his “little girl” the same sum if she didn’t accept the position. “My father was old-fashioned in that respect,” Goldie told CLARK alumni magazine in 2012. “He was not happy that the job was at the state hospital, and that it was mostly men working there. He didn’t think it was a proper place for a girl.” Goldie eventually turned down the job, and her father’s money.

One night during her first summer out of school, her brother Harry Corash ’21 brought home a friend for dinner. David Michelson had been working in Worcester and was scheduled to return to his home state of New Jersey the next day. Then he met Goldie.

“He said when he saw me walk down the stairs he had to get to a phone because his plans had changed,” Goldie recalled in the 2012 interview. “He knew he wasn’t going home.”

In 1926, Goldie become the first bride to walk down the aisle at Worcester’s just-built Temple Emanuel with her new husband. That same year, Clark’s own Robert Goddard ushered in the Space Age with the launch of his liquid-fueled rocket. The next year, Babe Ruth hit a staggering 60 home runs, Charles Lindbergh flew solo across the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis, and “The Jazz Singer,” Hollywood’s first feature-length “talkie,” was released.

Daughter Renee was born in 1931, and in September 1935 Goldie re-entered Clark (she’d earlier taken sociology courses there) to complete her master’s degree, the same month in which Adolph Hitler enacted the Nuremberg Laws in Germany that excluded German Jews from citizenship in the Reich. Her thesis would be titled “A Citizenship Survey of Worcester Jewry,” which examined why Jewish immigrants were reluctant to pursue U.S. citizenship.

She would not be the last in her family to attend Clark University. Seventy-seven years after Goldie earned her degree, her great-granddaughter, Deanna Minsky ’13, graduated from Clark.

⇔

Goldie’s compassion for others drove her to volunteer with numerous community service agencies, helping those who needed a hand. She had her personal tragedies — her beloved mother was killed in a car accident — and she experienced the sadness that went with outliving her brothers and longtime friends. And, as a life member of the women’s Zionist organization Hadassah, she was not one to ignore the horrors that beset Jews in other parts of the world.

Nonetheless, Goldie lived life with appreciation and optimism, gratitude and energy, personal discipline and curiosity.

Rabbi Seth Bernstein, who served at Worcester’s Temple Emanuel Sinai from 1986 to 2011, visited Goldie regularly from the time she was in her mid-80s to just a few years before she died. He recalls Goldie once asking him, “Rabbi, have you ever seen a cherry blossom like those on my tree? It’s the most beautiful cherry tree in the world.”

“Talk about carpe diem. That was one woman who seized every day,” Bernstein says. “She only saw the joy in it.”

Goldie had a gift for turning strangers into friends, says Sima Kustanovich, a concert pianist who has been with Clark’s music program for many years. A Russian Jew who, with her husband and son, moved from Leningrad to Worcester in 1979, Kustanovich was among the many immigrants whom Goldie took under her wing. “She was the first person who spoke to me in English, even though I didn’t know it at all,” Kustanovich told Chabad.org. “She did amazing things to help me many times in my life. Our close relationship was more than friendship — she was like family to me.”

Natalie Palley, who teaches English as a Second Language at Clark’s American Language and Culture Institute, shared a friendship with Goldie for more than 20 years. They often lunched at Goldie’s home to exchange news about what was going on in their own and their families’ lives.

The two women first met at a morning Midrash (Biblestudy group) led by Rabbi Bernstein. On that day, Palley had brought along her toddler, and the little boy was busily playing when Palley drew him aside to meet Goldie. “He just stared at her, and then a long rush of drool came out of his mouth,” Palley recalls. “Goldie beamed back at him, saying ‘I’m in love.’”

Goldie’s passion for theater manifested itself in the regular pilgrimages she and David made to New York City for Broadway marathons — seeing as many as four plays in a single weekend. She became a well-known actress, director and teacher in the Worcester area, bringing theater to children and adults in schools, clubs and area nursing homes. Goldie and David even retrofitted their basement into a theater — complete with stage and footlights — where she taught neighborhood children the elements of drama and music, and how to perform without fear and anxiety. The laundry room doubled as a dressing room, with a star on the door, of course.

When she had trouble finding performance venues, Clark offered her unfettered access to Daniels Theater in Atwood Hall.

“I can’t remember when I wasn’t coaching a play,” she once said. “That’s when I was happiest — when I had my hands on a production.”

Toward the end of her life, Paul Martin ’66 helped Goldie with small household projects and drove her where her legs couldn’t take her. The two spent many hours chatting, especially when he transported Goldie to and from her daughter’s and granddaughter’s homes in Maine. On those trips, she would sit beside him in the passenger seat and they would chat the entire time.

“We always had things to talk about,” he says. “Sometimes when I’d stop by she’d say, ‘Paul, you got a minute?’ and she’d start reciting Shakespeare. It was unbelievable the way she was reciting this stuff.”

Martin was not the only person to marvel at Goldie’s powers of recall. Bernstein tells how she was filmed for a course at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. When the videographer asked her to quote something from a play, she asked which one. “Hamlet,” he replied. “Well, what act? What scene?” Goldie asked. She then launched into a soliloquy, Bernstein remembers, “and the guy’s jaw just dropped.”

⇔

Tom Dolan ’62, M.A.Ed. ’63, a longtime fixture in the Clark administration, figures he knew Goldie for about 45 years, having met her through her brother Harry, with whom Dolan enjoyed frequent tennis matches (Harry endowed Clark’s Corash Tennis Courts). Dolan describes Goldie as a “Renaissance person. She was au courant on any subject — didn’t make any difference what you wanted to talk about.”

Her intellectual curiosity was fueled by the smorgasbord of political, social, economic, artistic and technological developments in the 20th century, surely one of the most rapidly changing epochs in human history. Her long life gave her the opportunity to ponder and respond to not just the beginning or end of important events, but entire cycles of change: the rise and fall of Germany (twice) and of the Soviet Union; the entire span of Chairman Mao’s reign in China; World Wars I and II, and wars in Vietnam, Korea and the Persian Gulf; the struggles over apartheid in South Africa and the turmoil of our own civil rights movement.

A play about Goldie’s life in the 1920s and ’30s might depict her as an emerging adult against a backdrop of the Jazz Age, Prohibition, the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl and FDR’s New Deal. She saw, in 1920, women in the U.S. gain the right to vote in federal elections. And a year later across the Atlantic — while Goldie was pursuing her bachelor’s degree and acting with the Komians, an all-women’s theater group at Pembroke College — Michael Collins signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty creating the Irish Free State.

Goldie witnessed the dawn of the nuclear age and the digital age, and, in between, the Age of Aquarius. Though she passed away before the election of a new president, she could have compared the administrations of 19 U.S. presidents who held office during her lifetime, from Theodore Roosevelt to Barack Obama.

⇔

Not surprisingly, some of Goldie’s most special philanthropic bequests married her love of theater with her devotion to Clark.

She endowed the David and Goldie Michelson Drama Fund, which supports many Clark theater initiatives.

“I cannot tell you how important this fund is to Clark’s theater program,” says Professor Gino DiIorio ’83, program director for theater arts since 2000. “It’s allowed our program to grow and thrive. We use it to support guest artists, classes, workshops — I can’t list all the things we’ve used it for.”

“Goldie would always come to shows and watch students work. She never wanted a big deal to be made for her,” he says. “Goldie was that kind of benefactor, the kind of person who enjoyed watching students thrive on their own. Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote: ‘An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man.’ Clark’s theater program is the lengthened shadow of one very special woman, Goldie Michelson.”

In 2009, Goldie made a generous gift to refurbish and rebuild the Little Center, including its black box performance space, which was renamed Michelson Theater. The marquee bearing her name provides visibility to the theater and announces current productions.

Goldie’s remarkable achievement of living past the century mark began to attract notice when she was about 108 and still going strong. Maine’s Senator Susan Collins sent her an American flag that had flown over the White House, which Goldie proudly displayed in her living room. And after qualifying as a supercentenarian at the age of 110, she received a photograph and congratulatory letter from President Obama (she sent him a thank-you note).

For two brief months this spring and summer, when she was officially the oldest person in the United States, media outlets from around the world flocked to publicize Goldie’s story. She died quietly at home, two floors above her basement theater — the final step on her wonderful walk.

“It never occurred to me that I would live this long,” Goldie once told an interviewer. “I just went on and on, and I’ve loved it.”