Dr. Fred Kron ’75 delivers strong medicine for physicians’ ailing bedside manners

It’s a scene that could play out at any hospital, any day: A young doctor nervously struggles to give a patient bad news.

practice giving bad news to a patient.

“Robin, you have leukemia,” he informs the johnny-clad woman. She sputters her disbelief, but his response is not comforting. “I think you need some time to yourself — I’m going to step out now.”

She angrily rebukes him, then demands to leave the hospital.

“I’m sorry to hear that, but it’s your choice,” the doctor says. The uncomfortable exchange ends, but Robin doesn’t exit the room. Instead, she fades to black, her image disappearing from the computer screen that sits on a desk facing the physician.

Robin is a virtual human, programmed to see and hear the doctor, and to respond with a span of emotions. The doctor is in training to improve his ability to communicate vital information and reassure a patient who has been staggered by a difficult diagnosis.

As the session concludes, the doctor receives a diagnosis of his own: He needs more work.

MPathic-VR is a computer training program designed to build trust and empathy in the doctor-patient relationship — the brainchild of Dr. Fred Kron ’75, who has been on both sides of these uncomfortable conversations. When he was 16, his mother passed away after a battle with lung cancer. He also has survived two bouts with cancer, including one immediately following his graduation from Clark. As a patient, he learned how discouraging it can be when your doctor seems to ignore your concerns.

Kron first realized how little value is placed on doctor-patient interactions when he was a medical student in the late 1970s.

“Professional skills like communication and the ability to observe, understand, and reflect on a situation are the foundation of medical practice,” Kron says. If communication training isn’t done right in the earliest stages “it’s not going to be done after you have your medical degree, and it’s certainly not going to be done after postgraduate [specialty] training. Generally, nobody looks over their shoulders again.”

Studies have shown that the very first piece of the doctor-patient meeting — “the patient interview” — is the most important part of any patient’s visit, Kron says. What a doctor learns in the interview is crucial to everything that follows. “The physical exam, the tests you order, the conclusions you draw are all based on developing trust and building a rapport with a person, who then may reveal to you their authentic reason for the visit, or complicating issues or problems,” he explains. Good communication also enables the physician to appreciate a patient’s diversity, background, fears, even hopes and dreams, “so you can treat the patient as a person, with kindness and respect.”

An incomplete patient history or simply a lack of personal connection can lead to an unsatisfactory doctor-patient relationship, or worse. Poor communication is consistently a top contributor to the medical errors that result in about 400,000 deaths and up to eight million cases of “preventable harm” per year, according to a 2016 study by Johns Hopkins researchers, published in the British Medical Journal.

Medical schools, hospital groups and even health insurers want to improve the status quo for a very practical reason, Kron says. Physician communication drives patient satisfaction. “If the doctor communicates well with a patient, that patient will give you top marks in a survey. And what does that mean to a health care organization? It gets higher reimbursements. Further, poor doctor-patient communication is the single best predictor of malpractice lawsuits.”

For many years, major foundations and national certifying bodies have pushed for better communication training for doctors. Although training requirements are now in place, the methods currently used have not been successful. “The challenge is to develop a novel method that provides learners with the ‘why’ of learning — as in, why do I have to know this stuff? — and that will actually change people’s behaviors in practice,” Kron says.

Enter Robin.

•••

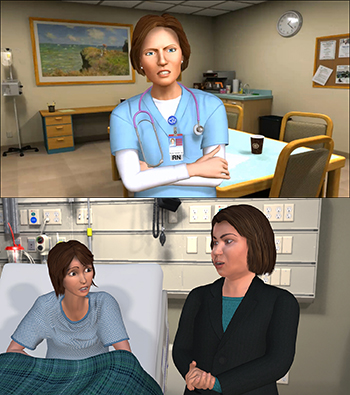

an oncology nurse (top) and leukemia

patient Robin and her mother, Delmy

Robin is one of the three virtual human characters created by Kron and his writing partner, D.C. Fontana, perhaps best known as the author of a dozen scripts for the original “Star Trek” series and for “Star Trek: the Next Generation.” The Robin scenario lets users work on breaking bad news. The other two characters are Delmy (Robin’s mother), from El Salvador, whose old-world values illustrate the need for cultural sensitivity; and Nicole, an oncology nurse, whose discovery of an intern’s blunder provides training in resolving interpersonal conflicts.

“We’re trying to give students the ability to gain experience in safe, virtual environments, with ‘conversational agents’ that look like people and with the ability to interact using the same range of verbal and nonverbal behaviors you would expect in conversation with another human,” Kron says.

MPathic-VR, a product of Kron’s company Medical Cyberworlds Inc., is a real-time, “bidirectional” system where the computer is able to determine the user’s cognitive strategy and read facial expressions and body language. The on-screen characters react in real time, according to the doctor’s behavior in various situations. The program interprets the doctor’s performance based on “grading” criteria on many user inputs.

Robin and her fellow MPathic-VR characters underscore the importance of learning to talk with and understand different types of people through realistic interactions, reflection and deliberate practice, a departure from traditional medical school communication training via lectures and workshops and “standardized patients,” people who have been trained to portray certain types of patient roles.

A doctor once told Kron that he learned more about working with patients and colleagues by watching the TV comedy “Scrubs” than he did in all four years of medical school. Kron wasn’t surprised: The “Scrubs” narrative allows viewers to engage with the characters and care about them. That’s why he and Fontana created a story arc for their training system, writing and evaluating it as if they were developing a television program — only instead of episodes, they created a series of richly drawn characters and thematically linked modules, each designed to highlight a different learning competency.

Medical Cyberworlds recently completed a trial with 421 second-year students at three medical schools. The students who went through the MPathic program were tested against a control group of students who had received traditional training.

“We proved with statistical significance that on global communication, the MPathic group did better,” Kron says. “What the students learned in doing the program stayed with them, and it was incorporated into their manner of communication. The most pronounced effect was in nonverbal communication — and that is the hardest thing to train.”

The MPathic group also reported that they appreciated the lessons more and had a better understanding of why the knowledge was valuable. Kron summarizes the findings in simple terms: “It works.”

•••

How does a physician in Madison, Wis., recruit a “Star Trek” writer to generate characters and stories for an interactive medical student training tool? It helps to be a part of the “Star Trek” universe. Since the late 1980s, Kron has been a television script writer with credits that range from “The Smurfs” to “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” which Fontana helped launch.

While doing an Air Force residency in radiology, Kron began questioning whether he wanted to stay in medicine. A friend encouraged him to pursue something that he really wanted to do: write for television.

Kron’s toddler daughter was a fan of the “The Smurfs.” During his free time, he drafted a “Smurfs” script and sent it to the story editor, who was amazed that “a doctor, Air Force major, radiology guy” would want to write for a Saturday morning cartoon — and that he was better than most of the writers working on the show.

Kron began landing more assignments and eventually worked on three different shows while still a radiology resident. Offered a promotion to chief resident, he declined so that he could continue writing, while practicing general medicine in Orange County, Calif.

Despite uncertainty about his future, Kron found it hard to let go of his medical career. Things turned around when his supervisor offered him the chance to attend a year-long course at the University of California, Irvine on doctor-patient communication. While there, he was interviewed by a TV news reporter intrigued by his status as doctor-writer.

That’s when he experienced his “a-ha” moment.

Kron told the reporter that writing isn’t much different than communicating with patients. “If you’re a good writer you understand drama, conflict, your characters, their backstory, what drives them, their fears, their hopes, desires. You understand universality of theme, how to talk to people to get a message across in a way they can understand. Why is it any different in a doctor’s office, where there basically are two characters playing out a scene?”

•••

“If I say, ‘I’m developing a program to help doctors talk with greater kindness and empathy to patients, and show them greater respect. What do you think about that?’ — a story will pop up.”

Kron finally decided to complete training in family medicine, and was accepted into residency at the University of Michigan. When he became a resident again in his 40s he quickly realized that while technology had improved, one significant aspect of the profession had not. “People still didn’t know how to talk to others, and still had no clue about why it was important.”

Kron began considering the possibility of using simulation and game-based technology to shape situations that register as authentic with both students and accomplished physicians. By interacting in these situations learners would develop a “toolbox of skills” that they could use in practice.

To engineer realistic “virtual humans” he consulted prominent psychologist Paul Ekman, a pioneer in the study of emotions and their relation to facial expressions.

Ekman told Kron that when he served on the faculty at the University of California San Francisco Medical School, he was denied a chance to lecture to medical students. Finally, he was given one hour to lecture students on recognizing patients’ nonverbal behavior and facial expressions. “That’s one hour out of four years of medical school,” Kron stresses.

Ekman joined a core group of people to work with Kron — professionals from medicine, entertainment, high-tech psychology and simulation. Interestingly, each had tales to share about medical interactions gone wrong.

“That’s not unusual,” Kron says. “All I have to do is tell someone what I do. If I say, ‘I’m developing a program to help doctors talk with greater kindness and empathy to patients, and show them greater respect. What do you think about that?’ — a story will pop up.”

Like the one about a doctor who wouldn’t prescribe palliative care for a dying friend because it would be a waste of time. Or the surgeon who blithely dismissed a patient’s anxiety about a procedure. Or the patient who woke from exploratory surgery to be brusquely told by his doctor that one of his testicles had been cancerous and was removed. The doctor then walked away without a word of explanation or comfort for his stunned patient.

•••

Kron is now considering marketing the MPathic-VR system for use in fields other than medicine.

“The strongest suggestion we get is that it can be a tool to look at how people act differently according to race or gender,” Kron says, noting that implicit biases create problems in medicine and many other areas of society. At the end of each scenario, the system provides an after-action review. “You see yourself in conversation and receive feedback based on what the system sees you doing. The computer is set up to look for specific things in an unbiased way, and you can’t cheat it or argue with it. It asks you to reflect on your performance then go back and try again.”

Kron credits former Clark professors Ed Trachtenberg, Rudy Nunnemacher and John Reynolds for nurturing his ability to reflect on his actions. “They really made me stop and think about who I was, what I was doing, and took an interest in me personally,” he says. “Years later, a lot of the things they said came home and I began to understand them. It was tremendously helpful.”

Also helpful was an on-campus job at Physical Plant. One of his supervisors was “a real gentleman, a great guy. As a student, I didn’t appreciate it, but looking back he taught me about self-sufficiency, learning how to do even such basic things as cleaning up after myself. I think of him every time I scrub a floor, every time I polish and dust, every time I wring out a mop.”

His own experience, Kron says, is just one example of how Clark students learn to develop creative, innovative ways of solving problems. And that’s not only because of the University’s excellent professors, he adds — it’s the “Clark milieu” that challenges students to use knowledge in the pursuit of self-actualization and altruistic goals.

•••

Those who have used the MPathic-VR program report that its dramatic situations give them a low-stakes way to practice handling high-stakes conversations, Kron says.

“It brings the students into the encounter so they are empathetically engaged with the patients. The story is also important: They want to complete a module to discover what happens next.”

The beginning, middle, and end are written, but Kron isn’t revealing any spoilers about Robin’s fate.

He will say that no matter how many times she expresses fear or anger, or threatens to walk out, there will be an opportunity for the doctor to help Robin understand she has an ally. Done right, the message is as simple as two words: I care.

This story originally was published in CLARK alumni magazine, fall 2016