In a recent lecture at Clark University, Ousmane Power-Greene, professor of history, put words to the African-American struggle against “King Cotton” and the desire to find a homeland — and a place to build community.

The Graduate School of Geography hosted Power-Greene on Sept. 14 as the first speaker in the school’s Fall 2016 Colloquium Speaker Series. His talk, titled “King Cotton’s Exiles: Slavery, Abolition and the Making of the African American Diaspora,” presented research for his next book and posed several questions about the concepts of cotton as “king” in the American South and the African-American diaspora.

“These black American exiles often acknowledged their flight in political terms that resonated with other political exiles living in places such as London during the 1850s,” Power-Greene said. “Other black Americans formed refugee communities in Canada, Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa. They settled down and built communities in these places even while they were being deeply connected to political events at home and at times planned to return to their families if and when slavery ended.

“As such, this continuity and dislocation challenged black American exiles to, on the one hand, imagine a community, a ‘promised land,’ while they acknowledged the United States as their home.”

Power-Greene said he and other scholars “still have yet to identify how the rise of King Cotton shaped the form and the content of the abolition movement.” His current and future research seeks answers to this and other questions surrounding the diaspora.

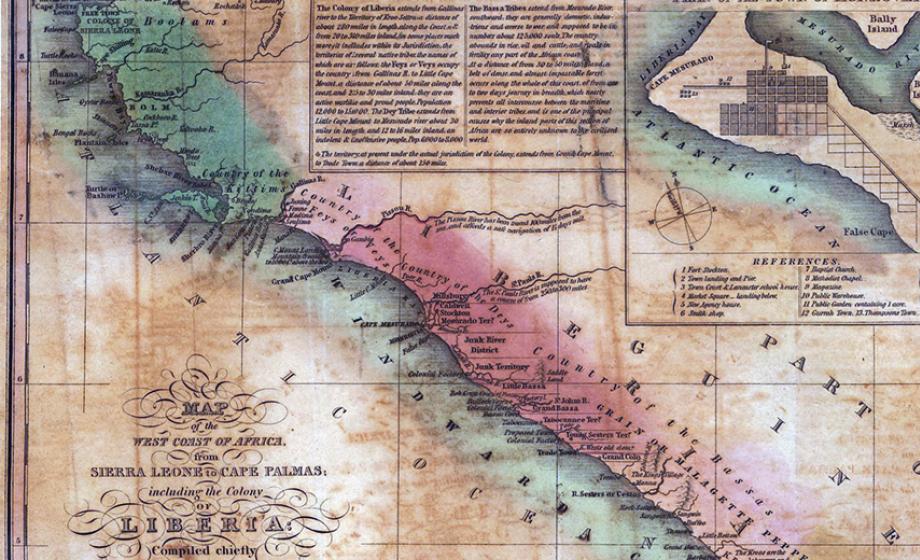

His recent book, “Against Wind and Tide: The African American Struggle Against the Colonization Movement,” tells the story of African-Americans’ battle against the American Colonization Society (ACS), founded in 1816 with the intention to return free blacks to Liberia. Although ACS members considered free black colonization in Africa a benevolent enterprise, most black leaders rejected the society, fearing that the organization sought forced removal. As Power-Greene’s story shows, these African-American anti-colonizationists did not believe Liberia would ever be a true “black American homeland.”

Yet, he writes, despite the anti-colonization movement, “black Americans would time and time again consider leaving their communities or even the country when white racial hostility reached unimaginable levels of barbarity.” In the years after the collapse of Reconstruction, many African-Americans considered “emigration to Haiti or colonization to Liberia as a last resort.”

The American Historical Review called Ousmane-Greene’s 2014 book “well-written and cogently argued … a must-read for scholars interested in the African Colonization Movement.”

Above, a 19th-century map of the colony of Liberia (courtesy of the Library of Congress)