Professor Mark Turnbull earns John A. Timm Award

The highest honor given by the New England Association of Chemistry Teachers is the John A. Timm Award, which recognizes “an individual who has made exceptional contributions to the education of young people in chemistry.”

Clark University chemistry students, current and former, will hardly be surprised to learn Professor Mark Turnbull received the award at NEACT’s summer conference. His reputation is to hold his students to exacting standards in the lab and classroom while also guiding them to master difficult concepts and solve complex problems. His daughter introduced Turnbull to the website Rate My Professor, which he’d never visited, and he appreciated one student comment appearing beneath his name that read: “Don’t take his course for the grade. Take it to learn something.”

“I don’t want to discover the cure for cancer, I want one of my students to.”

His own career was inspired by great teachers, among them Dr. Lawrence Benjamin, a former DuPont chemist who left the corporate world to become an AP chemistry teacher. Benjamin’s expertise, insight and motivation helped launch Mark and fellow students into the field.

Turnbull earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in chemistry from the University of New Hampshire, and taught at a high school in Londonderry, N.H., before attaining his Ph.D. from Brandeis. He joined Clark’s faculty in the fall of 1986 and came under the welcome tutelage of Karen Erickson, Al Jones and the legendary Ed Trachtenberg, whose organic chemistry class inspired equal parts awe and fear in his students.

Turnbull and his longtime research partner, Chris Landee, professor of physics, conduct research into molecular magnetism. “The guiding principle is to use our understanding of structure, bonding and geometry to control the bulk magnetic properties of a material at the molecular level,” Turnbull notes on his Clark research profile. The professors collaborate with international teams of organic and inorganic chemists, theoreticians and condensed physicists.

His favorite part of the job is “watching the headlights go on” — that moment when a student masters a particularly vexing problem. “Something happens,” he says. “Suddenly, the student says, ‘Oh. Why didn’t you tell me it was that easy?’”

He is continually impressed by the caliber of Clark students. “Our average student is a good, solid scientist who is capable of doing anything,” he says. “And our best students I would put up against anyone’s students.”

However, he laments a noticeable decline in basic math skills among incoming students in recent years. The professor notes the stunned faces looking back at him when he informs his students that calculators will not be allowed on his exams. “I don’t like the overreliance on devices,” he says. “These are tools, not a replacement for thinking. If you can’t do the math yourself, then you can’t recognize a ridiculous answer when you get one.”

Turnbull introduces his students early to the rigors of peer-reviewed publication — five of his undergraduate students are working on manuscripts for submission. It’s a world he knows well. He has authored 200 published papers, edited a book, and is co-editor of the Journal of Coordination Chemistry.

His reputation for engaging students extends beyond the Arthur M. Sackler Sciences Center. Turnbull is a familiar presence at Clark performances and sports events, and he regards it an honor to serve soon-to-be graduates at the annual Senior Class Brunch.

“Professor Turnbull was my professor for both Intro and Organic Chemistry, and he really pushed me to be a better student,” says Courtney Pharr ’17, a pre-med student and member of the varsity volleyball team. “I don’t think I would have learned as much or enjoyed chemistry as much if I hadn’t had him as a professor. And he is so supportive of all of his students outside the classroom. The fact that he went to most of my home volleyball games really just goes to show how much he cares about his students.”

Mark Turnbull is fond of a saying that he attributes to his wife, Susan, in which she summed up his teaching philosophy: “I don’t want to discover the cure for cancer, I want one of my students to.” At the very least he will continue to make his students’ headlights shine as they grapple with the intricacies of the chemical universe.

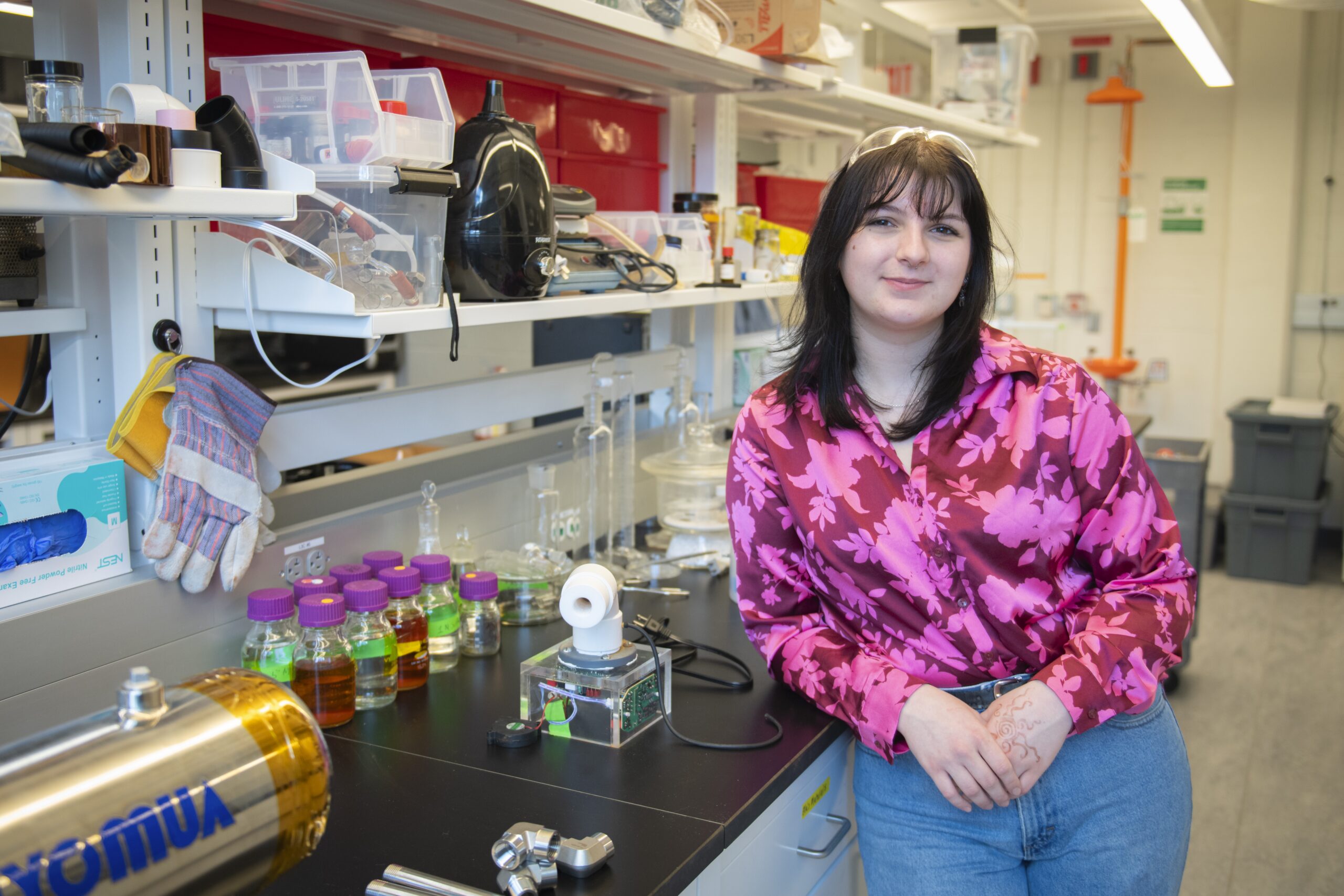

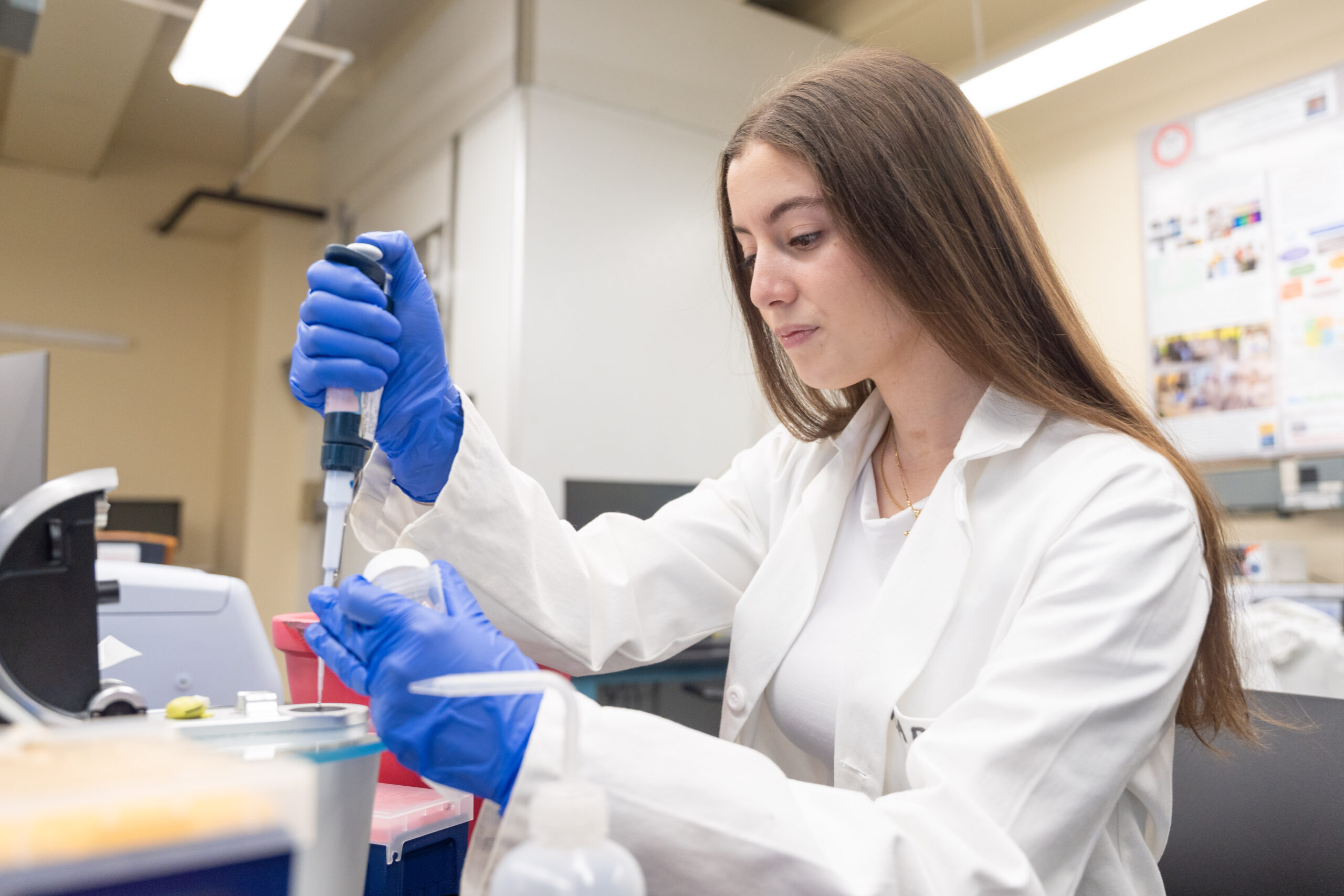

Top: Prof. Mark Turnbull, center, works with students in his office at the Arthur M. Sackler Sciences Center.