First, the view.

economic development for the

Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

in conversation at his Boston office.

Massachusetts Secretary of Housing and Economic Development Robert “Jay” Ash ’83 occupies the corner office on the 21st floor of Boston’s John W. McCormack Building. Panning from due west to southwest, his windows offer an unobstructed view of the Longfellow Bridge, the entirety of riverfront Cambridge and the Boston Common. The office of his boss, Governor Charlie Baker, is just a short walk away, under the golden dome of the Massachusetts State House.

Ash, 56, remembers his first time in this office two decades ago when he worked as chief aide to State Representative Richard Voke. Upon returning from a meeting, the legislator asked Ash for a recap.

“I said, ‘Richie, I have no idea,’ ” Ash laughs. “I was enamored by the view.”

In ways both subtle and direct, some within his control and some beyond, and often spurred by his Clark experiences, Ash has made his way to this office with the skyline seemingly at arm’s reach. As the longtime city manager of his hometown of Chelsea — just north of Boston — he earned a reputation as a tireless innovator who pulled the embattled blue-collar city out of receivership and set it on a hopeful course for renewal. In his current position he is again receiving high marks, most recently for his part in the negotiations that lured General Electric to relocate corporate headquarters from Fairfield, Conn., to downtown Boston.

His mission is to balance the economic equation in the best interests of all Massachusetts residents, from the deep-pocketed who seek investment opportunities in the state, to those with nothing to their name, including a permanent address. He has known tough times himself — the kind you call upon when making difficult decisions; the kind that thicken your skin but hopefully don’t harden your heart.

Indeed, the key to Jay Ash’s success may lie in the fact that this view from the 21st floor was so hard-earned, and light years from the view he started with.

♦♦♦♦♦

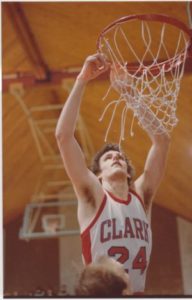

when Clark reached the NCAA

Elite Eight.

Ash jumped into politics as a 10-year-old living in Chelsea when he worked on school committee candidate Richard Clayman’s campaign. (“Richie Clayman, down the street,” Ash explains, as if everyone knows the guy. This, one assumes, is a Chelsea thing.) In 1976, Ash’s sophomore year of high school, he scoped out the local candidate for Congress, and after assessing the guy had no shot he went to work on Massachusetts Sen. Edward Markey’s first victorious run for federal office.

Less than two years later, Ash arrived at Clark, knowing only that he wanted to find a career in government and, in the meantime, play basketball.

Basketball sorted itself out quickly. Ash, who stands 6 feet 7 inches, was a forward who also played a lot of center since the team’s starter often found himself in foul trouble. The Clark teams of the early 1980s were some of the best in the school’s history — they had size, speed and success. Ash led the Cougars to the NCAA Division III Elite Eight during his senior season, averaging 13.5 points a game for a team that amassed a 23-4 record. He earned the honor of captain, won the Fred C. Herbert Trophy and finished his career with a 54.2 percent field goal percentage after 73 games, currently good for eighth all-time at Clark.

“Jay was a consummate team player. His role was to rebound and defend,” recalls his coach, Wally Halas ’73, M.P.A. ’93. “When he had the perfect shot from within 16 feet he was supposed to take it. Jay’s attitude was, ‘Whatever you think is best for me and in the long run will help the team, that’s what I’ll do.’ He worked hard for what he earned, and he never took a bad shot.”

There was more than basketball at Clark. Jay met his future wife, Susan Carney ’83 (the couple have two sons). He was so committed to the University that he returned as a trustee for several years, departing the board when he accepted his state appointment.

“For me, coming out of Chelsea, I wasn’t sure who I was, but I knew I wasn’t like everybody else,” Ash says. “Clark really helped nurture the man I turned out to be.”

Part of this nurturing was provided by Sharon Krefetz, professor of political science, who taught Ash in her Urban Politics course and with whom he still remains in contact. (Ash returned to Krefetz’s classroom as a guest lecturer a number of times before her retirement last year.) Krefetz’s class steered Ash toward an understanding of government that extended beyond electoral politics and embraced the idea of public service. “I give Sharon Krefetz the most credit for getting me to understand the public policy side of it,” he says.

Urban Politics famously ended each semester with a debate in which students argued between two forms of local governance: one led by an elected mayor and the other by an appointed city manager who handles the day-to-day tasks of running a city. Krefetz recalls Ash choosing to lead the manager side of the argument.

For me, coming out of Chelsea, I wasn’t sure who I was, but I knew I wasn’t like everybody else. Clark really helped nurture the man I turned out to be.

No one could have guessed that he would spend 15 years at Chelsea’s helm, orchestrating the renaissance of a city so battered by political corruption and entrenched poverty that the state had seized control of all its municipal functions for much of the 1990s. Under Ash’s leadership from 2000 to 2014, according to The Boston Globe, nearly $1 billion was invested in Chelsea, including more than 2,000 market-rate residential units and an influx of companies like Home Depot, Starbucks and Market Basket. When Ash left the job, $500 million in projects were being planned, including four hotels and a $100-million FBI regional headquarters.

A study conducted by Northeastern University and the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston analyzed 20 of the state’s poorest communities, and found that Chelsea had experienced the biggest job growth, nearly 11 percent, from 2001 to 2013. This was at a time when statewide job growth hovered at less than 1 percent. Among those visiting Chelsea to see how the Ash administration accomplished it was Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen. Northeastern economics professor Barry Bluestone told the Globe, “Jay may know more about economic development and business attraction than almost anyone else in the Commonwealth.”

“He did such an amazing job that he caught the attention of people like Baker,” Krefetz says of her former student. “It’s really close to a miracle that Chelsea is in the decent shape that it’s in, instead of receivership.”

♦♦♦♦♦

as a Clark University trustee.

Ash approaches his oversight of housing from a rare personal perspective: as a teenager he endured periods of homelessness.

“We never slept out on the street, never slept out in a car, but when my parents split up we went to my mother’s friend’s house,” he says. For a while, Jay, his mom and his brother lived under the same roof with a family of seven. By the standards set by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, “I was homeless as a kid.”

Periods of “housing insecurity,” as Ash calls it, persisted into his adult life when his mother fell behind on rent and found herself losing her home. Ash, now solidly into his Clark academic and basketball career, informed Wally Halas that he would have to leave school to find a job. Halas convinced his player to make some phone calls, one of them to a parish priest, who found housing for his mom. Ash could stay at Clark.

Since he took charge of housing and economic development for the state in January 2015, Ash has connected the two seemingly disparate silos through “economic self-sufficiency,” the notion that a person with a home, a job and an education not only benefits on a personal level, but is a contributor to the common good.

“When I talk about economic security, there’s my case,” he says, referring to his near departure from Clark. “My earning capacity would have been greatly reduced.”

We both agree that having families spend weeks, months and in some cases over a year in hotels is not good for the family unit. I think a common bond we share, the Republican governor and Democratic secretary, is that we see the things that government has historically done haven’t always worked, and yet people haven’t been able to get away from what hasn’t worked.

But he cautions people from oversimplifying his political beliefs based on his backstory.

“You might read into it that I’m more likely to believe there should be more ample affordable housing. I’m not sure it does mean that,” he says. “The other side to that story is my mom was in affordable-subsidized housing the rest of her life, which was maybe 25 years, and I’m not sure that’s meant to be the way either.”

He adds, “There should have been something along the way to help her leave the public system.”

Even though Ash, a Democrat who personally experienced homelessness, and Republican Governor Baker, the son of a former U.S. deputy undersecretary of Health and Human Services, come from contrasting economic backgrounds, they seem to agree more often than not on the housing aspect of Ash’s job. Baker’s latest budget has changed the funding mechanism for assisting homeless families, and overall funding has increased.

“We both agree that having families spend weeks, months and in some cases over a year in hotels is not good for the family unit,” Ash says. “I think a common bond we share, the Republican governor and Democratic secretary, is that we see the things that government has historically done haven’t always worked, and yet people haven’t been able to get away from what hasn’t worked.”

Baker and Ash have cultivated their relationship over two and a half decades. Ash was working as Chelsea’s executive director of planning and development in 1991 when the city filed for bankruptcy and the state placed the community under receivership. Baker, who at the time was secretary of administration and finance for then-Gov. William Weld, made budget decisions that both impacted Chelsea and brought him in contact with local government employees.

The two grew closer over the years, and spoke regularly during Baker’s 2014 campaign for governor. Publicly, Ash could hardly keep his support quiet, even when asked to do so by the Chelsea City Council. He recalls a Boston Globe reporter asking him whom he’d support in the general election, to which Ash responded, “I’m not allowed to endorse anyone, but I’m looking forward to the Baker administration.”

Ash attended Baker’s election-night party, “sweating it out” as Baker beat then-Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley by 40,000 votes. Baker called Ash a few days later, making the Clark grad his first cabinet appointment.

♦♦♦♦♦

Ash has attacked his first year with vigor. Colorful Post-it notes cover his office walls and dot the free-standing boards that bear charts and reports. Studies and other documents form piles on any available flat surface. He drives himself to each of his public events and proudly claims to have covered 9,000 miles in visits to more than 100 communities.

You have to keep your eye on the long term, but long term is in four-year increments here.

The position oversees a broad swath of government, distilled into three parts: economic development, affordable and low-income housing, and consumer affairs, which includes business licensing and banking and insurance regulations.

Baker scored political points for reaching across the aisle, but those familiar with the job, and with Ash, credit the governor with more than just fulfilling campaign-trail promises of bipartisanship. Greg Bialecki, Massachusetts’ previous secretary of housing and economic development, sees a distinct commonality between Baker and Ash. “It’s the style of both of them that they are pragmatic and focused on solving problems,” he says.

Bialecki believes Ash’s experience steering Chelsea through rough waters brings needed perspective to the policies coming out of the State House, because he understands that while Massachusetts has made gains with economic development and housing, success is “unevenly distributed across the state.”

Ash uses the analogy of a relay race to describe his role: he inherited the baton from Bialecki and will pass it on to someone else later, but for now he gets to run with it.

“You have to keep your eye on the long term,” he says “but long term is in four-year increments here.”

Krefetz, for one, has long suspected Ash will run for elected office someday. “He really has excellent political instincts,” she says, and “he won’t compromise his principles.”

It’s a line of thinking echoed by others who believe Jay Ash’s public profile will only rise. Asked about his aspirations, Ash smiles, and offers a response of equal inscrutability to the one he gave the Globe reporter fishing for his endorsement for governor.

“I get concerned with low ceilings so I’m always looking for higher ceilings, and we’ll leave it at that.”

The view, it seems, might be endless.

Top: Gov. Charlie Baker (l.) and Jay Ash (center) visit a Massachusetts clockmaker.

This story originally appeared in the spring 2016 issue of CLARK alumni magazine.