Red beanies, good friends and the shadow of war

It’s been more than three quarters of a century since the Class of 1941 first assembled on the campus to hear a talk by Dean Homer P. Little and to get our classroom assignments. That was in September 1937, a notable day in our lives. Clark then had five buildings — Jonas Clark on Woodland Street, the old chemistry building on Maywood Street, the library building on Downing Street, the geography building on Main Street, and Estabrook at Woodland and Charlotte streets. Atwood Hall was built the following year when we were sophomores.

In the days ahead, we would grow accustomed to the neighborhood and to the quaint Clark customs of the time. We freshmen were issued our red “beanies” and warned to wear them at all times when on campus lest we be nabbed by some sophomore vigilante. We took our revenge on the sophomores later on when we dragged them through the cold water of the pond at Crystal Park in the annual rope pull contest. We won the pull the following year, too. Class of 1941, undefeated forever.

Clark then was a small place — maybe 200 undergrads and 100 grads. No females, save for the occasional woman from one of the graduate schools. Tuition was $100 a semester — or was it $150? Seventy-eight years on, the memory sometimes slips a cog. There were three fraternities — one for Catholics, one for Protestants, one for Jews. Clark provided us a reasonably good education by the standards of the time. Of course, the astonishing increase in knowledge of the past 75 years, particularly in the sciences, has left the colleges of that era — not just Clark — looking quaint.

For example, Clark’s president was Wallace Atwood, a well-known geographer. The dean was Homer Little, a trained geologist. I took geology and I listened to Atwood’s occasional lectures. They knowledgably discussed the physical world — mountains, glaciers, deserts, oceans, volcanoes, earthquakes. All very interesting. But what I now realize is that they really didn’t have a clue about the dynamics of our whirling, rumbling planet. The whole field of plate tectonics lay years in the future.

And that goes for the whole universe that Einstein and Hubble uncovered. Quantum entanglement, Higgs bosons, the Big Bang, quarks, neutrinos, dark matter, dark energy — I doubt any of them was even thought of in the old chem. lab. The humanities, my bailiwick, were somewhat better off. I got good instruction in Shakespeare’s plays, Greek civilization, European history and classical music. Subjects like that have not been overrun by events.

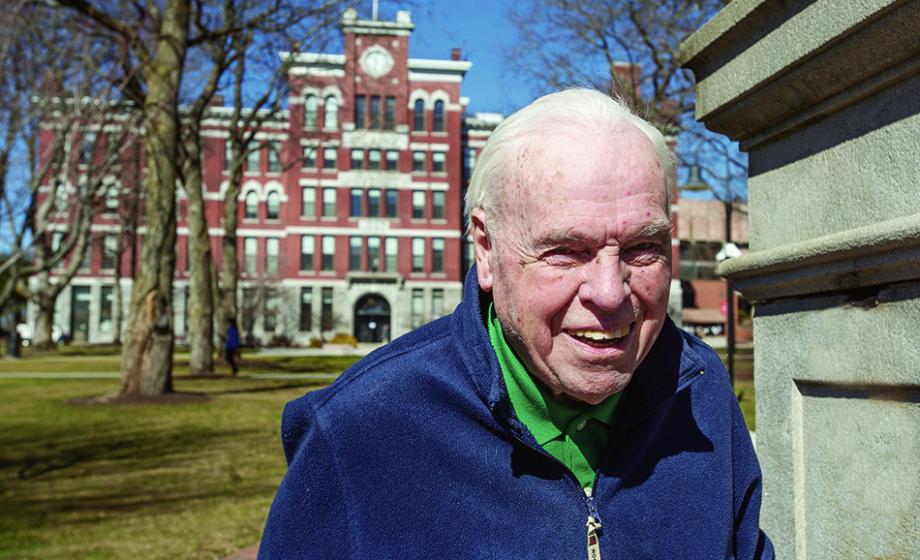

Jonas Clark Hall was then, as now, the center of things — first floor, offices; second floor, classrooms; third floor, biology labs; fourth floor, assembly hall; and gymnasium in the basement, where we did daily calisthenics under the supervision of Ernest Whitman. The big building had been designed by my grandfather, Stephen C. Earle, a well-known architect in Worcester in the 19th century. But he didn’t boast about it. He once told his daughter, my mother, “I wasn’t the architect, I was the draftsman,” which suggests that old Jonas Clark was not the easiest of clients. For years the rumor had it that Mr. Clark was prepared to turn it into a factory if the college idea didn’t work out.

One thing that the Clark of yesteryear shares with the Clark of today is that it was a lively, stimulating place. Here I was, a Yankee farm boy from the country suddenly a part of a cross-section of America. Clark had nearly everyone — Irish, Italian, Greek, Swedish, Jewish students, and others. I learned much from them outside the classroom. My best friend turned out to be Ben Bagdikian ’41, born in Turkey. His family had been part of the Armenian diaspora, and it was from him that I learned about the ghastly Armenian genocide in 1915-1918.

I still have a clear image in my mind of the various faculty members — Ames, Brackett, Blakeslee, Hoagland, Potter, Melville, Bosshard, Lucas, Maxwell, Churchman and others. We respected them in a way that perhaps is different today. I think we would have been astonished at the current escapades at some college campuses where student protests have led to cancellations of speakers and programs not considered politically correct. The only example of thought censorship at Clark had nothing to do with the students. That was the notorious Scott Nearing case, when President Atwood turned out the lights during a talk being given by Nearing, a radical Socialist. It got national headlines and earned Clark some unenviable publicity. Clark’s motto is “Fiat Lux” which made the episode doubly ironic. Atwood never wholly recovered his reputation.

As time went on, we learned more about the Clark story, particularly the famed visit of Sigmund Freud in 1909. Another noted figure was Robert Goddard. Those of us who had grown up in or near Worcester remembered how he used to startle the neighborhood night times with his fiery rocket experiments on Newton Hill. That was before he moved to Auburn with his paraphernalia. We met him once — when he was brought into our geology class and introduced by Dean Little. He was visiting from New Mexico, where he was continuing his rocket experiments.

It was during our years on campus that Dr. Hudson Hoagland and his colleague, Gregory Pincus, began their mysterious experiments in an old carriage house on Downing Street. Pincus was noted for his “fatherless rabbit” experiments at Harvard. President Atwood, suspicious of the whole thing, gave them no encouragement, so they went to Shrewsbury and founded the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology, famed for developing the first birth control pill.

We competed in several sports — soccer, baseball, tennis and basketball. I was four years on the tennis team, the last as co-captain. Our basketball fortune got a big boost when the new gym was opened in 1940. (It’s now the cafeteria.)

Our routine was rudely interrupted one day in September 1938, when New England was devastated by the worst hurricane in memory. More than 500 died, mostly in Providence. The Clark campus was a clutter of fallen trees and debris. Woodland and Maywood streets were impassable. Dean Little mobilized us into working groups and we gradually cleaned things up. Classes resumed a couple of days later.

Our college years were tinged with an ominous shadow — the war in Europe. We had grown up in the aftermath of World War I, hearing grim tales of the Argonne and Belleau Wood, and we wanted no part of war. I think that we were all isolationists in 1937. The Battle of Britain stirred our sympathies and we were thrilled by Winston Churchill’s speeches, but we still hoped against hope that we would never have to go.

We graduated in 1941. Commencement speaker was Lowell Thomas, the newsman who had made Lawrence of Arabia a household name. The baccalaureate sermon was given by Paul Tillich, a famed German theologian. His English was so heavily accented as to be incomprehensible.

So out we went into that sunny June morning, eager to start the journey of life. Six months later the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. I think that every one of us went into the military. I spent four years in the Navy.

Surviving members of the Class of 1941 — all three of us — let’s pause for a moment and indulge our memories. Here we are 75 years after, on the final lap, and Clarkies to the end.

— By Albert B. Southwick ’41, M.A. ’49

Albert B. Southwick is the retired editorial page editor of the Worcester Telegram & Gazette. He continues to write a regular column about Worcester history for the newspaper and has authored several books. This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of CLARK Alumni Magazine.