Auschwitz survivor Elie Wiesel died last week at 87 years old, but not before working unflaggingly to keep the memory of those lost during the Holocaust alive and to encourage the world to remember and understand what both victims and survivors endured. “Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices,” he said when he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1986.

Ten years later, Wiesel came to Clark University to attend the installation of Debórah Dwork as Rose Professor of Holocaust History. Dwork recalls Wiesel’s encouragement in founding the first doctoral program in Holocaust History and Genocide Studies at the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, which opened in 1998.

“Elie Wiesel honored Clark, and honored me, with his participation in my installation as Rose Professor,” she says. “He believed in the importance of education, and he championed my view that a doctoral program in Holocaust history is essential to ensure future engagement with that dark past.”

“Later, when we had secured the Kaloosdian/Mugar Professorship in Armenian Genocide Studies, which expanded the mandate of Center scholarship and teaching, he wrote me a one-word note. ‘Bravo!’”

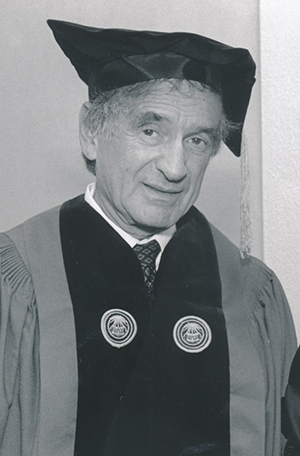

Wiesel, Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University, also reviewed Dwork’s book “Children With A Star,” which held special meaning for him, as it’s a history of his generation. Clark awarded him an honorary degree, doctor of humane letters, in 1996.

There is one place where all aspects of this extraordinary tragedy are explored: Clark University.

“Without Elie Wiesel our thinking about the Holocaust would not be what it is,” says Strassler Center Director Thomas Kuehne, Strassler Family Chair in the Study of Holocaust History. “Deeply saddened at his death, we may draw comfort from keeping alive his powerful stance against indifference in the face of hatred and cruelty.”

Shortly after accepting the Nobel Peace Prize, Wiesel and his wife, Marion, established The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity to fight indifference, intolerance and injustice, according to its mission statement. The organization’s goals echo one of the final sentences of his Nobel speech: “Our lives no longer belong to us alone; they belong to all those who need us desperately.”