Close-ups from far away

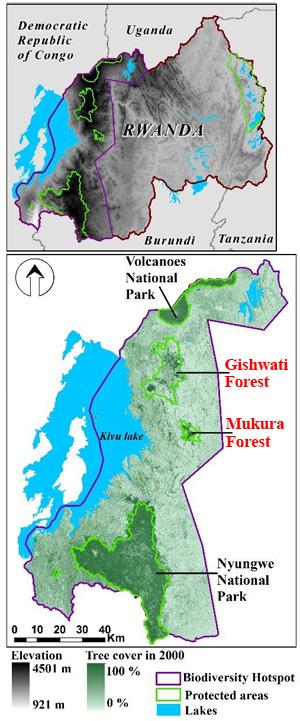

Thanks to high-resolution satellite imagery provided by the DigitalGlobe Foundation, Clark doctoral student Bernadette Arakwiye can now see the forest AND the individual trees (plus trails and village buildings) in her approximately 860-square-mile study area in the Gishwati and Mukura forests of western Rwanda. The detailed imagery lets Arakwiye plot her route through that remote and mountainous region before she arrives, saving her precious money and time.

Arakwiye is conducting a pilot study in these two forests in preparation for her dissertation research, which will focus on monitoring forest degradation in western Rwanda with the aim of assessing opportunities for restoration. Arakwiye, who grew up in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, hopes that her research results will eventually be used to inform her government’s forest-restoration policy. She explains that after the 1994 genocide, forests were degraded or cut down to resettle refugees or grow food. In the process, the eastern chimpanzee’s habitat was broken up, while that of the mountain gorilla was reduced and degraded.

The high-resolution imagery is free for Arakwiye’s use thanks to Clark geography professor John Rogan and his former student Andrew Steele ‘08, now senior product specialist with the Asia-Pacific Division at DigitalGlobe. Their efforts have resulted in a mutually beneficial memorandum of understanding between the DigitalGlobe Foundation and Clark University for an initial period of one year. In return for free imagery, Clark will share with the foundation innovative ways that faculty and students use DigitalGlobe products in research and teaching.

As a geography major at Clark focusing on geographic information science and remote sensing, Steele witnessed first-hand the need for more accessible high-resolution remote-sensing imagery.

“When I was at Clark,” Steele recalls in a recent email, “I painfully felt the bottleneck of projects depending on the availability of imagery data, and I didn’t want the same issue to stifle creative and interesting work done by the students and researchers at Clark. After I arrived at DigitalGlobe in 2009, I felt as though I could give back to Clark by sponsoring several research projects that required high-resolution imagery.”

Associate Provost and Dean of Research Nancy Budwig, says, “This agreement symbolizes the creative ways student learning, faculty research excellence and alumni networks come together synergistically to improve all. The community of practice established here holds immense promise.”

The partnership is a potential boon for Clark researchers both inside and outside the Geography Department. The capture of imagery from satellites is a costly undertaking, and, according to Steele, DigitalGlobe provides the highest-resolution satellite imagery commercially available. Founded in 1992 as WorldView Imaging Corporation, DigitalGlobe now operates four satellites, which between them supply panchromatic and multispectral (including near and shortwave infrared) imagery at a range of resolutions from 30 to 50 centimeters. Their cloud-based library contains more than six billion square kilometers of imagery from the past 15 years.

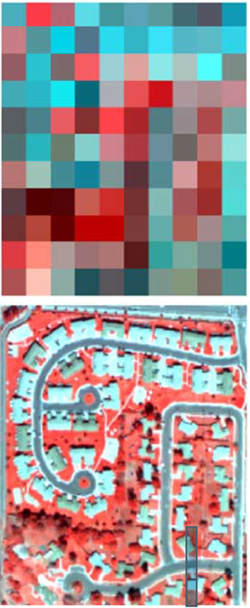

Rogan notes that limited access to high-resolution imagery has always been an impediment to its use in research. “What we’ve done in the remote-sensing/environmental-monitoring community is make do with U.S.-government-sponsored Landsat imagery which, while free, is at much lower resolution. And while Google Earth, which uses DigitalGlobe imagery, has transformed the way a lot of people look at remote sensing, you can’t manipulate data in that format. And even in Google Earth many remote areas are simply not available at the higher resolutions.

“I think the true benefit of this agreement is that it can change the way our faculty and students address their study areas. There’s nothing like high resolution to make you feel good about what you’re doing. Coarser-resolution data are so abstract that you have to be very, very skilled at image interpretation to extract information.”

Rogan also points out another advantage of high-resolution imagery: in a pinch it can substitute for actual trips into the field in regions that are unsafe, whether because of political instability, the presence of illegal activity or dangers to health.

A specialist in landscape and fire ecology, optical remote sensing and GIScience, Rogan recalls that his first opportunity to access DigitalGlobe imagery came about eight years ago, when he was trying to assess the impact of Hurricane Dean on the Yucatan forests of Mexico. Around that time Steele had begun on occasion to furnish his former professor with small images for educational use, and the two remained in touch. Now Clark is one of only three universities, in company with the University of California at San Diego and the University of Minnesota, participating in this type of formal agreement with the DigitalGlobe Foundation. Rogan hopes the relationship eventually might even evolve such that internship opportunities with DigitalGlobe will be available to qualified Clark students.

Rogan anticipates that Clark research proposals featuring the use of this imagery will look especially attractive both to research-funding agencies and to prospective partner/client organizations who could not afford the imagery on their own. He’s especially excited about the positive impact the agreement will likely have beyond the Clark campus.

This story is part of our 7 Continents, 1 Summer series, which highlights the interesting work that Clark students, faculty, alumni and staff are doing all over the world. Have a great story of your own to share? Let us know and we’ll be in touch.

“I feel very fortunate to have this opportunity,” he says. “From a research perspective, we are now in a world—especially with environmental monitoring—where there are many people bidding for contracts. This opportunity gives us a competitive advantage. And given that we are well-connected, implicitly others will benefit.”

For example, Rogan notes that students are encouraged to work with outside organizations, many of whom have no remote-sensing staff. For these clients, low-resolution imagery is a source of frustration.

“But if they can see imagery that looks like what they’re used to seeing on Google Earth, that really helps a lot,” he explains. “The level of communication is much better. And that’s what the DigitalGlobe Foundation wants—to create a level of understanding beyond their traditional users.”

Meanwhile, back in Rwanda…

Bernadette Arakwiye recently headed into the Gishwati and Mukura forests. She is not new to the rigors of on-the-ground research in western Rwanda. While studying conservation biology prior to attending Clark, she spent several years studying mountain gorillas and golden monkeys while a research assistant at the renowned Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International’s Karisoke Research Center. In a 2011 article on the Fossey Fund’s website, the center’s then deputy director, Felix Ndagijimana, was quoted as saying: “Bernadette Arakwiye…is a role model and motivation for other Rwandan university graduates, especially women who wish to pursue careers in science, research and conservation.”

Arakwiye’s access to DigitalGlobe’s imagery left her feeling prepared to take this next important step in her doctoral research.

“The high-resolution images have helped me identify specific, representative sites that I can visit to look at changes in forest cover,” she says. “I’ve also identified villages in those areas where I can ask people questions like ‘what are your perceptions of forest change in the area?’, ‘which areas would you like to see restored?’ and ‘what species would you like to be used in the restoration?’ to inform a solution that will account for social-economic as well as biophysical needs.”

Arakwiye, who is awaiting final confirmation of a NASA Earth Systems Science Fellowship, thinks it’s unlikely that she could have done her pilot study without the high-resolution imagery.

“Without this imagery, the next best thing would have been Landsat images, which are 30-meter resolution. You go from 30-centimeter down to 30-meter resolution—it’s a big difference,” she explains. “With DigitalGlobe I was really able to get ready for fieldwork. It’s a lifesaver.”