All the world’s a classroom to Jude Fernando

Sitting on the edge of the bed of a pickup truck with a driver “maniacally navigating” the chaotic streets of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Associate Professor Jude Fernando is relaxed and smiling, with his hair and long beard blowing in the wind. He’s explaining what connections the five Clark University graduate students accompanying him should be making en route from one fieldwork location to the next.

“He was talking about economic development, the disparity between social classes, political instability … relating it to what we saw that day and also what we need to pay attention to wherever we were headed next,” relates Christopher Owens, M.A. ’17, who described the journey from earlier this year. “He was teaching amidst the chaos.”

It’s that kind of teaching — and emphasis on learning from others — in difficult situations where Fernando and his students excel.

Fernando’s research in the International Development, Community and Environment department focuses on post-disaster response and humanitarian assistance in relation to livelihoods and governance. In addition to studying the after effects in Haiti of the 7.0-magnitude earthquake in January 2010 and Hurricane Sandy’s impact in October 2012, he has traveled with students to Nepal, which suffered a devastating 7.8-magnitude earthquake in April 2015. This summer, he’s working with two students in Sri Lanka, his native country, to study the effects of gender inequality in tea production.

It’s his goal for every student to learn about themselves in addition to what they’re researching while doing fieldwork: To learn if they don’t like being in the field, if they like it enough to pursue it — or if they love it enough to make it their life’s work.

This story is part of our 7 Continents, 1 Summer series, which highlights the interesting work that Clark students, faculty, alumni and staff are doing all over the world. Have a great story of your own to share? Let us know and we’ll be in touch.

Fieldwork — which includes collecting data and interviewing individuals, among other tasks — often forces students to adapt to unfamiliar and changing situations and collaborate with people from a variety of disciplines.

For example, Fernando has for years taken both undergraduate and graduate students pursuing degrees in International Development and Social Change, Community Development and Planning and Geographic Information Sciences for Development and Environment to Haiti. While there, the groups work with Clark alumni — whom Fernando credits for helping the field school work — employed by programs funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and other nonprofits.

“The students think it’s an opportunity, opening possibilities for acquiring knowledge and making connections between what they study and what they want to do in the future,” Fernando says. “The common thread is to give them the experience of combining theory and practice.”

There are meetings to prepare the students for what they’ll encounter prior to traveling, but not everything can be planned. Fernando said upon arriving in Haitian refugee displacement camps, for example, some students started questioning their own education while others felt guilty and upset at what they saw. One camp to which Fernando took his students had an estimated 100,000 people living there.

“They’ll say ‘we shouldn’t be here’ or ‘this isn’t what we planned,'” he says. “I tell them it’s a learning experience.”

Despite the difficult conditions, Fernando says, most students adjust and no one has left before a scheduled departure date. Once they get comfortable, the students take care of one another and, each night, the group reflects on its work and engages in interesting discussions.

The students “see there are two narratives — frustration, but also happiness and pride in the country,” he says.

Owens, who’s pursuing a degree in International Development and Social Change, said he couldn’t “overstate how important” the nightly group meetings were.

“It was subtle some days and very overt on other days, but this time allowed us to process our thoughts and emotions with him,” he said. “He guided us through our individual mental processes so we could create our own meaning of what we witnessed. He is exceptionally patient and always providing his insight.”

Out of the dozens of students from a variety of disciplines he has brought to difficult areas, many have decided to pursue careers that will change the lives of countless others.

“Some of the most scared are the ones who want to go back again,” he says. “One scared student is now applying for the Peace Corps.”

Another student, Lelani Williams, M.B.A./M.A. (CDP) ’16, created her own company, Sun Top Solar Cookers, after doing field work in Haiti in May 2015 and seeing the enthusiastic response from residents when Fernando used one to cook a meal. After additional business development, she plans to take her company back to Haiti to help “empower Haitians to build a better country,” she said.

Biology major Maya Hodgson-Dottin ’17, is traveling with Fernando to Sri Lanka this summer to study the socioeconomic impact of tea production. She’ll return to Clark with a LEEP project and further spread her knowledge and first-hand experience to the community.

Owens, who already completed a career in the Coast Guard, came to Clark “to connect previous humanitarian and overseas experiences with academic perspectives and research.” He said the Haiti trip provided experience he can build on in the future.

Fernando’s students aren’t the only ones learning on these trips. Like any good teacher, he learns alongside them.

“It’s a good learning experience for me,” Fernando explains. “It makes me aware of the gap between what we teach and the skills demanded by the job market.”

But it means more to his students.

“He’s always teaching,” Owens says. “He’s great in the classroom and he’s brilliant at it in the field.”

Here’s a glimpse of Fernando and his students’ life-changing fieldwork from the most recent trips to Haiti (an 11-day trip in March 2016 and a 12-day trip in May 2015).

Haiti March 2016

During his most recent trip to Haiti, his ninth, Fernando took his students to a refugee camp in Port-au-Prince, one of three locations in the country where he does fieldwork and research. The group talked with residents of the camp, displaced from the 7.0-magnitude earthquake on Jan. 12, 2010, about their experiences as well as their livelihoods since the disaster. “While visiting the camps, we worked to understand how terms like ‘prolonged displacement,’ ‘sustainable agriculture’ and ‘humanitarian aid’ really look in the field. We met with people in camps who gave us their personal narrative of how they struggle with clean water, security, land ownership, access to jobs and education all combine to create a new and ongoing daily reality,” IDSC graduate student Christopher Owens says. (All photos below courtesy of Jude Fernando)

Fernando’s students Christopher Owens, Isabella Kaganowski, Kelly Eaton, Kelsey Hopkins and Sweta Shrestha, along with their guide Keneril, walk through a displacement camp in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Fernando discussed being uncomfortable with the students prior to their arrival in the camp, but encouraged them to learn to work through cultural differences as well as the information they would hear from the residents there.

Fernando’s students prepare for a meeting while inside the refugee camp in Port-au-Prince, Haiti in March 2016. Owens said this was the first time any students in the group worked as researchers or academics in a developing nation. “This meant that we had to work as a team with goals that didn’t leave some tangible change, but rather to gain understanding of what we experienced,” he says.

Fernando’s students had to establish trust with people they spoke with inside the displacement camps. In this photo, Fernando says the conversation became tense while residents spoke about their frustrations. He guided his students ahead of time to “accept the frustration, deal with it” while finding strategies to work with the camp residents. “We learned that even in these communities, poverty is not equal. We learned that generalized statements about homelessness, development and recovery do not tell the complete story,” Owens says.

The students’ fieldwork also involved speaking with farmers and agricultural groups created to train local farmers in sustainable practices. Here, the group walks back from a protected area near Port-au-Prince, Haiti. “In the agricultural visits, we heard first-hand accounts about how farmers struggle to learn new techniques, but also how implementation of these new techniques is challenging,” Owens says.

The students discovered a group of artisans in a craft village who made these intricate metal works out of pieces of scrap metal found throughout the country.

The group on one of the hikes into the mountains to learn about how agriculture and cultural practices have led to deforestation and erosion over the course of Haiti’s long history. Owens says being in this small group, which was based out of the Haitian Foundation for Sustainable Agricultural Development’s (FONHDAD) compound in Bas Boen, meant Fernando could give each person focused mentoring each day. “Also, because we didn’t have some larger programmatic goals, we were able to focus on being observers, students and colleagues,” he says.

Haiti May 2015

During this May 2015 trip to Haiti, Clark students conducted fieldwork in displacement camps as well as interviewed farmers and local stakeholders to learn about the impact of the energy crisis on agriculture-based livelihoods, poverty, climate change and conflict in the villages of Merceron, Tri Marche and Bas Boen, according to Lelani Williams M.B.A./M.A. (CDP) ‘16. Some of the fieldwork was done to satisfy educational requirements, but also benefitted nonprofits like World Vision and FONHDAD. (All photos below courtesy of Jude Fernando)

When on trips like this one, the students — and the instructors — all get involved. In this photo, Fernando takes the lead in the kitchen preparing a meal for the group.

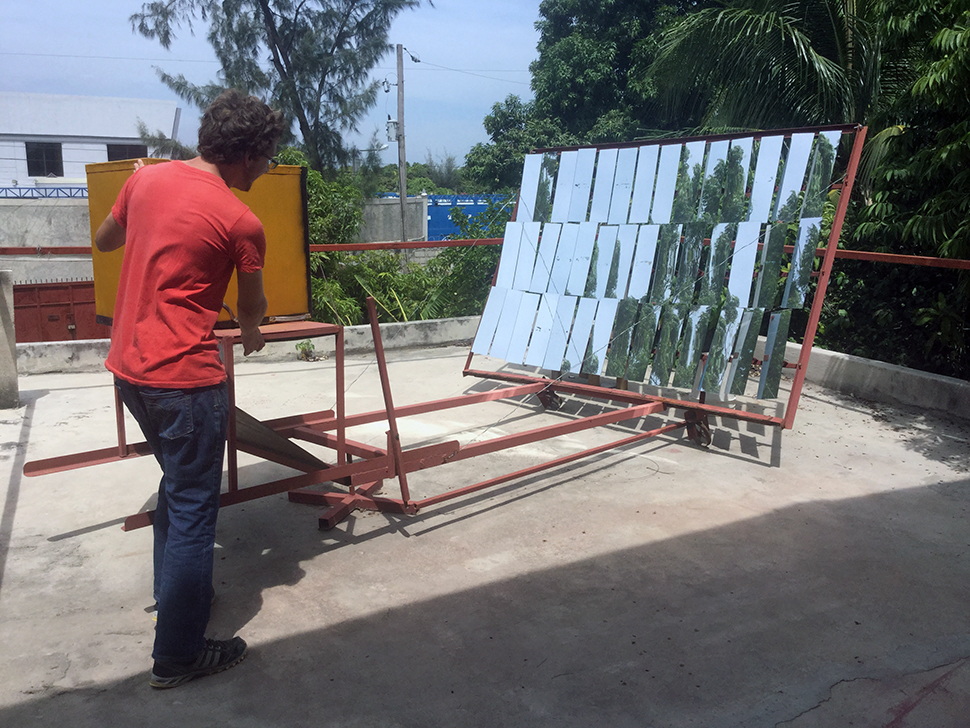

Despite its location in the Caribbean and hot, sunny climate, solar power isn’t widely used in Haiti. In this photo, a student examines an array of solar panels.

Seeing Fernando cook a meal with solar power drew great interest from those gathered for the demonstration. Solar power, which isn’t widely used in the country despite its location and climate, could help contribute to new solutions for poverty. Lelani Williams’ company, Sun Top Solar Cookers, evolved after Williams took this trip to Haiti and saw Fernando’s demonstration. “People went crazy,” she says. Using solar power to cook can have a far-reaching impact on reversing deforestation and increasing women’s economic impact in Haiti.

In this photo, students view an alternative solution to housing. Following the disasters there, The Love & Haiti Project, a nonprofit, challenged people to develop sustainable housing. The example above shows a Superadobe made with mud and plastic drink bottles.

The group met daily to talk about their fieldwork. Fernando says the discussions were a valuable part of the trip and that the group, which included students in International Development and Social Change, Community Development and Planning and Geographic Information Sciences for Development and Environment programs, worked through living and learning together.