‘A great cultural export from Asia to the rest of the world’

Over the past decade, specialty mushrooms, especially shiitake, have won over Americans. Renowned food writer and Clark University alumnus Mark Bittman ’71 hailed the increased availability of shiitake for American cooks. Meanwhile, a Boston chef-turned-wholesaler recalled that in the 1990s, “nobody knew what a shiitake mushroom was. … Today, even Domino’s is advertising shiitake pizza, so we’ve reached a tipping point.”

First cultivated in China between 1000 and 1100 A.D., the shiitake is revered in Asia for its culinary and reputed medicinal qualities. It’s the second most cultivated mushroom in the world, and in the United States, shiitake mushroom farming has jumped almost 20 percent in two years. It’s now a $33 million market nationwide, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Northeast boasts a number of shiitake growers who are turning a tidy profit.

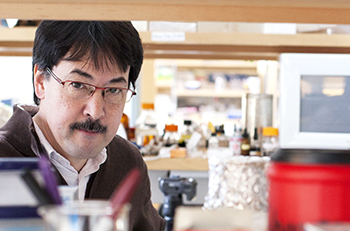

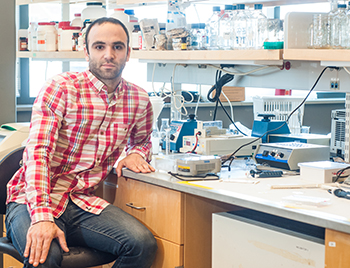

But to Clark University biologists and co-principal investigators David Hibbett and John Gibbons and their international research partners, the shiitake is more than a key ingredient in Japanese nabe soup or a Bittman recipe. The shiitake, with the scientific name of Lentinula eddodes, also presents researchers with a way to understand the genetic diversity, evolution and global spread of a species – and the naming process that has helped humans grasp the complexity of life around them.

Furthermore, their research into shiitake “could inform biofuel production,” Hibbett says. Shiitake break down lignin, the cellular material forming the tough, fibrous parts of wood, and “lignin is the major barrier to … producing bioethanol from coarse plant material.”

The researchers, therefore, won Community Science Program support from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Joint Genome Institute, which will provide “invaluable” services — DNA and RNA sequencing, bioinformatics and other analytical work to unlock the information encoded in shiitake genomes, according to Hibbett. The DNA molecule stores a cell’s genetic information; the RNA transmits this information when a cell produces proteins.

The biologists want to understand how and when the shiitake — whether wild or cultivated — spread throughout the world, how wild shiitake are related to cultivated versions and how genetically diverse the species is. To better grasp this evolutionary and biogeographic history, they will study the whole genomes — containing the complete DNA and genes of each organism — in shiitake and other closely related species of Lentinula.

“We are going to generate high-quality reference genomes, and with those in hand, we will screen many cultivars [shiitake samples cultivated and selected for desired characteristics] to find out what the genetic diversity is,” Hibbett explains.

“We’ll use the Lentinula genomes to study the genetics of decay … and try to understand how the ability to decay wood varies and evolves,” he adds. “And some of our partners will study shitake mushrooms as they grow, so they will isolate the RNA from the developing mushrooms to try to understand the developmental genetics.”

An international effort

According to the project’s proposal, “this will be the first in-depth genomic survey of any genus of wood-decaying Agaricomycetes,” which includes most of the world’s mushrooms.

The more than 200 strains of shiitake and its relatives that will be analyzed in the project come from across the globe. The cultivated shiitake occurs in Asia, but species of Lentinula can be found everywhere except Europe, Africa and the polar regions — “as far as we know, that is,” Hibbett notes. “It’s one of the organisms that we humans have domesticated and brought all over the world.”

The project’s 24 researchers likewise hail from across the globe: Japan, Brazil, China, Spain, France, Hungary, the Netherlands and the United States.

“This is truly an international collaboration,” Hibbett says. “This project and others at Clark rely on these international networks of faculty working together.”

The research partners also are traveling overseas for the project.

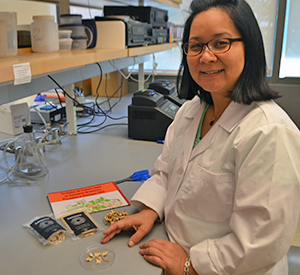

Hibbett will head to Kyoto this fall to connect with collaborators at a meeting of the Mycological Society of Japan. Meanwhile, his lab hosted Kazuhisa Terashima, a research associate from Japan’s Tottori Mycological Institute (TMI), the world’s leading center for shiitake research; his visit was sponsored, in part, by Clark’s Office of Sponsored Programs and Research. And in early June, Noemia Kazue Ishikawa, a visiting researcher at Clark for the past six months, traveled to TMI on a research exchange; she just returned to her work at the National Institute of Amazonian Research in Manaus, Brazil.

As part of her research for the Center for Integrated Studies of Amazon Biodiversity, Ishikawa is involved in a sustainable agriculture effort with the Yanomami Indians of the Amazon. To support their communities, they are harvesting a native species of shiitake —Lentinula raphanica — and selling the mushrooms and mushroom powder to high-end restaurants. Samples of these shiitake are being used in the research project.

“These international collaborations are critical to research innovation and a testament to Professor Hibbett’s stature as a leading scholar in this area,” says Nancy Budwig, associate provost and dean of research at Clark.

The Japan connection

Hibbett’s interest in shiitake stems from his doctoral research, as well as his post-doctoral study at TMI in 1991-92. He published several articles on shiitake, but after 2001 he moved on to other subjects. For him, this more recent shiitake project is a return to familiar territory.

But Hibbett’s ties to Japan go even deeper. His maternal grandparents are from Okinawa, the southernmost archipelago of Japan, and this fall he will return to the islands with his mother, now 91, for a special festival on the Okinawan diaspora. His father, born in the United States and of European descent, is an expert in Japanese literature and an emeritus faculty member for Harvard University’s Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies.

This story is part of our 7 Continents, 1 Summer series, which highlights the interesting work that Clark students, faculty, alumni and staff are doing all over the world. Have a great story of your own to share? Let us know and we’ll be in touch.

Before and during World War II, Hibbett’s mother and her parents lived in California, but they left just in time to escape the U.S. government’s incarceration of Japanese-Americans in internment camps. Meanwhile, his father studied Japanese at Harvard and joined the Army.

He “was recruited by the U.S. government to translate intercepted Japanese messages, so it’s kind of funny that later I found myself being paid by the U.S. government to study Japanese,” thanks to a National Science Foundation grant during graduate school, “but for completely different reasons — economic and scientific competition, not military,” Hibbett says.

Over the years, Hibbett has continued to receive support from the federal government, including the Joint Genome Institute, for his basic research on fungal genetics and evolution. He studies white-rot fungi, which break down lignin. By helping decay rotting wood, white-rot fungi have played an important role in the cycling of carbon between living things and the environment for some 290 million years, according to his research. Shiitake are a white-rot fungi, but scientists have not yet pinpointed when they first emerged.

In Japan, shiitake prefer the shii tree (a kind of oak); hence, the name: shii plus the Japanese word for mushroom, take. The farmers committed to quality use “log cultivation methods to grow superb mushrooms” by inserting shiitake spawn into holes drilled in logs, Hibbett explains. But large-scale, industrial farms, mostly in China, use cheaper, quicker methods, growing shiitake on bags filled with sawdust and wheat or rice bran.

In the United States, many small-scale farmers have adopted the more traditional approach, using logs from oak, maple and other hardwood trees to grow shiitake.

The shiitake: revered worldwide

When Terashima visited Clark recently, he accompanied Hibbett and Ishikawa to shiitake farms in Massachusetts and saw how Americans have adopted the Japanese methods of growing shiitake.

Because shiitake cultivation is a multibillion-dollar global market, there could be a lot of interest in the researchers’ findings.

“I’m interested in the international movement of cultivars to cause problems,” Hibbett says. “When people move cultivars around, they do so using a very high density of spores, so you have the potential to have escapes of cultivars. That may have already happened in Asia, where people have been growing shiitake for a long time.”

Biologists are concerned that escaped cultivars could “replace or interbreed with the native populations,” ultimately reducing the diversity of wild shiitake, he explains. “That should be a concern for the people in the shiitake industry because the wild shiitake are sources of genetic diversity” that might benefit commercial cultivation or lead to disease resistance.

It’s easiest to explain in terms of people. We’re fascinated to understand where we came from. Biologists want to answer the same questions about other species and about whole biotas [animals and plants of particular regions or habitats].

The researchers also are interested in the taxonomy — the classification and naming — of the shiitake. Hibbett already has explored the shiitake’s taxonomy as part of his dissertation on mushrooms falling under the genus Lentinus. Shiitake mushrooms have a long, involved history of evolving names and classifications reaching back to the late 19th century; in 1976, a biologist switched the shiitake from the genus Lentinus to a new genus he called Lentinula, based on morphology and anatomy; Hibbett’s doctoral research, using molecular methods, supported that taxonomic transfer.

But why are biologists so interested in the historical naming of a species?

“It’s easiest to explain in terms of people,” Hibbett says. “We’re fascinated to understand where we came from. Biologists want to answer the same questions about other species and about whole biotas [animals and plants of particular regions or habitats]. Why do the forests in northeast Asia resemble those of eastern North America? It really has to do with understanding why the natural world has the distribution it does” and whether “the historical patterns tell us anything about historical barriers to movement and how that might affect the movement of organisms today.”

Because of the shiitake’s significance in Asian culture and cuisine, immigrants transported spores from their homelands to grow mushrooms in their adopted countries. For example, Hibbett says, “Noemia told me that her grandfather brought shiitake when he immigrated to Brazil.”

Hibbett has firsthand experience with Asians’ adoration of shiitake. In 1994, while researching shiitake mushrooms, he traveled to China’s Zhejiang Province, where the first shiitake are said to have been cultivated by Wu San Kwung during the Sung Dynasty (960-1127 AD). The Chinese deified Wu long ago and opened a temple in his honor.

When Hibbett and other researchers attended a shiitake conference in Wu’s village, home to his temple, the Chinese asked them to assemble in the lobby of the Mushroom Town Hotel.

“We step out into the bright sun, and the townspeople all are lined up along the sides of the road, and the high school band is playing, and all along the parade route are children dressed up as mushrooms,” Hibbett recalls. “We get the gymnasium, and there’s this two-hour ceremony. It was like the opening of the Olympics.”

He keeps a ceramic Wu figurine in his lab as a whimsical reminder of the mushroom’s significance. “The shiitake is a great cultural export from Asia to the rest of the world.”