Antarctica or bust: Clark’s southernmost research

Though nearly 10,000 miles from Worcester, Massachusetts, Antarctica holds a significant place in the history and lore of Clark University.

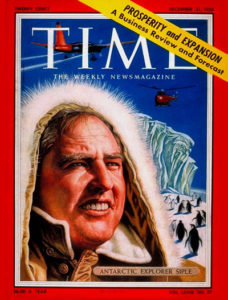

Today, ongoing scientific research by Clark-affiliated researchers is again focused on Antarctica. They want to more clearly define the true threat of global warming – and how quickly human-induced climate change may lead to destabilization of the continent’s ice.By the middle of the 20th century, geographer and polar explorer Paul Siple, Ph.D. ’39, had traveled seven times to the southernmost continent — more journeys to the South Pole than anyone. On several of those expeditions, he accompanied the renowned polar explorer Adm. Richard E. Byrd, who described Siple as “a born scientist and the best-equipped man there is for this kind of work.”

As part of a three-year project by Clark geographer Karen Frey and others to understand surface changes in the cryosphere — the frozen ocean water — of West Antarctica, Luke Trusel, Ph.D. ’14 (pictured at top), traveled to the continent in 2010-2011. Their research resulted in a Nature Geoscience article last October that the online magazine Slate called “the first to comprehensively study the sensitivity of warming air temperature on the stability of ice shelves in Antarctica.”

Siple’s Clark Mountains

77 degrees 16 minutes south and 142 degrees 0 minutes west.

77 degrees 16 minutes south and 142 degrees 0 minutes west.

Those are the coordinates for the Clark Mountains of Antarctica, named by Siple for his alma mater. He also mapped and named the peaks for his Clark geography professors: Mount Wallace Atwood, a double peak for the University’s geographer-president and his son, also on the geography faculty; Mount Burnham; Mount Ekblaw; Mount Clarence Jones; and Mount Van Valkenburg. He named Mount Ruth Siple after his wife.

Siple’s dissertation for Clark explored “Adaptations of the Explorer to the Climate of Antarctica.” His publication became famous because of 12 pages where he developed the theory and coined the phrase “wind chill factor,” a favorite topic of discussion for North American meteorologists and weather watchers everywhere.

Wind chill — the scientific calculation of air temperature plus wind speed that determines how cold people really might feel — was a phenomenon with which Siple had become intimately familiar as a scientist conducting pioneering research at the South Pole in the mid-’30s.

His first exploration was in 1928-31 as a 19-year-old Eagle Scout from Erie, Pennsylvania; he was selected by Byrd from 60,000 Boy Scouts competing for a spot on the trip.

“When he came to the Antarctic, not even its outline was complete on the map, and when he left it, the exploration was almost finished,” wrote B.B. Roberts in The Geographic Journal just after Siple’s death in 1968.

It was during his and Byrd’s third expedition, from 1939 to 1941, that Siple named the Clark Mountains and tested the wind chill theory, according to the late Clark President Richard P. Traina’s 2005 book Changing the World: Clark University’s Pioneering People: 1887-2000.

“Life during these expeditions was beyond harsh,” Traina writes. “In 1957, for example, Siple and 17 others spent an entire winter together at the South Pole — which is dark from September 22 through March 22. During that stay, the temperature sometimes dropped to more than 100 degrees below zero.”

On a prior expedition from 1933 to 1935, Siple had served as Byrd’s scientific leader and chief biologist at the United States’ first permanent station at the South Pole.

Siple wrote of the prolonged dark: “We were like men who had been fired off in rockets to take up life on another planet. We were in a lifeless, and almost featureless, world. However snug and comfortable we might make ourselves, we could not escape from our isolation. We were now face-to-face with raw nature so grim and stark that our lives could be snuffed out in a matter of minutes.”

Trusel, Frey and climate change

Since Siple’s expeditions, many explorers and researchers not only have passed by the Clark Mountains but also have become familiar with the features named for the Clark graduate: the Siple Coast, Siple Island, Mount Siple, Siple Ridge and Siple Station.

Trusel is one of them. Beginning in December 2010, he participated in a six-week research expedition based out of a large ice core drilling site on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. His flight to the research camp carried him past the Clark Mountains and over the Siple Coast and Siple Dome, both named for the renowned explorer.

He considered his research trip to Antarctica “both personally and academically rewarding.”

“I had an incredible time and would love to go back,” said Trusel, who has been working as a postdoctoral scholar at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). “We’ve been trying to get down there again to collect ice cores in order to develop climate records that predate our satellite observations.” However, he added, “it’s very difficult to get to certain areas of Antarctica, particularly the Amundsen sector of West Antarctica, because there’s so little infrastructure. Unfortunately, this is one of the most rapidly changing areas in Antarctica.”

Trusel’s research on the Antarctic ice sheet has made waves worldwide due to the Nature Geoscience article, for which he was lead author and Frey, co-author, along with several others. Their study projects a doubling of surface melting of Antarctic ice shelves by 2050 if greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel consumption continue at the present rate.

“We concluded that surface melting can intensify very quickly as the climate warms and potentially threaten the stability of parts of Antarctica in this century,” said Trusel, who will continue his research as a professor for Rowan University next fall. “This has already occurred in places like the Antarctic Peninsula where we’ve observed warming and abrupt ice shelf collapses in the last few decades. Our model projections show that similar levels of melt may occur across coastal Antarctica near the end of this century, raising concerns about future ice shelf stability.”

More recently, a study published in Nature in March 2016 by Robert M. DeConto of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and David Pollard of Pennsylvania State University confirmed that melting on the ice surface “would be the leading mechanism of change to Antarctica’s ice over this century and beyond. Their sea level rise projection for this century (from Antarctica alone) was about 1 meter if greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated,” Trusel explained.

Together, the two publications “go against the mainstream scientific focus right now, which is on how the ocean is melting Antarctica from below,” he added.

“Scientifically,” Trusel said, “it was good to have our work essentially corroborated by an independent study [in Nature], but the projections of change for Antarctica are certainly alarming.”

Yet, as Trusel told Slate, he is still hopeful that the effects of climate change can be somewhat mitigated. “We see our clear human influence,” he noted, “and that means we can change.”

Siple, who spent six years total in Antarctica from 1928 to 1957, might never have imagined the ice shelf slipping away. But like Trusel, he understood the pull of Antarctica – and its impact on those who had traveled there.

“Once you’ve been here, there’s something a little special about you – everyone feels it, and so do you,” he said. “I think this may be what draws people down here, and even though they hate it, they feel it’s worth it. It will last them a lifetime.”