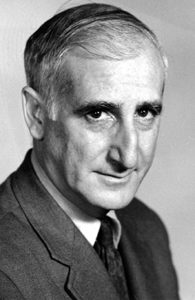

Ben Bagdikian ’41, who died March 11 at the age of 96, enjoyed a storied career in journalism. He won the Pulitzer Prize, reported on prisons, poverty and civil rights, and defied the federal government by helping publish the Pentagon Papers, thus securing one of history’s greatest victories for freedom of the press.

Later he became an influential media critic — The New York Times described him as “a celebrated voice of conscience for his profession” — particularly in his seminal book, “The Media Monopoly.” In it he examined the role a handful of corporate media giants play in shaping and controlling the news for a mass audience.

Bagdikian’s journalistic legacy, not to mention his penchant for challenging authority, was rooted at Clark University. While editor of the student newspaper, then called The Clark News, he hit on the idea of changing the name to The Scarlet, in honor of the school color. As recalled by his longtime friend, Albert Southwick ’41, M.A. ’49, who was the newspaper’s managing editor, President Wallace Atwood objected to the change, believing the word “scarlet” would be too closely associated with the “red menace” of Communism.

“Atwood was suspicious, but Ben went ahead and did it anyway,” Southwick says. The first issue of The Scarlet was published on Nov. 3, 1939. (The run-ins with Atwood never dimmed Badgikian’s affection for the place. He was awarded an honorary degree in 1963 and served as a Clark trustee from 1964 to 1976.)

Bagdikian’s family fled the Armenian Genocide in Ottoman Turkey when he was a baby, settling in Massachusetts. According to Southwick, Bagdikian studied science at Clark, thinking he might pursue a career in biology. Shortly after graduation he was visiting a friend at the Springfield (Mass.) Morning Union newspaper when the editor informed him that the paper needed a reporter. He offered the job to Bagdikian, who accepted. The world had lost a biologist but gained a crusader.

After serving as an Air Force navigator in World War II, Bagdikian took a job with The Providence Journal,where he was part of a team that earned a Pulitzer for coverage of a bank robbery. He also traveled throughout the Deep South in the early 1960s for a series detailing the civil rights movement through the eyes of oppressed families. In later years he chronicled the ravages of poverty in the United States and investigated prison conditions by going undercover as a convicted murderer in a Pennsylvania maximum-security penitentiary.

His most celebrated work occurred during his tenure as national editor at The Washington Post. In his obituary, the Post recounts Bagdikian being summoned to Boston for a clandestine meeting with Daniel Ellsburg, the onetime defense analyst who was willing to hand over the so-called Pentagon Papers, a secret history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam (The New York Times already had published excerpts but had been ordered to cease by a federal judge for national security reasons).

Bagdikian retrieved the documents from Ellsburg and delivered them to Editor Ben Bradlee. He was then among the editors and reporters who reviewed more than 4,000 pages and debated the consequences of publishing their sensitive contents.

“Mr. Bagdikian was one of the strongest voices in favor of publication,” the Post wrote, “arguing that the government could not use the cloak of ‘national security’ to limit what newspapers could print. He uttered a line that neatly summed up the principle involved: ‘The only way to assert the right to publish is to publish.'” The Post printed the documents, a decision that withstood a Supreme Court challenge.

Bagdikian often trained his reporter’s eye on the media, writing several books that were fiercely critical of the trends that he saw eroding best journalistic practices and ethics. He concluded his long career as dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley. The New York Times recalled a lesson he would impart to his students at the outset of each course: “Never forget that your obligation is to the people. It is not, at heart, to those who pay you, or to your editor, or to your sources, or to your friends, or to the advancement of your career. It is to the public.”

His old friend Al Southwick puts it another way. “He always had a feel for the underdog.”