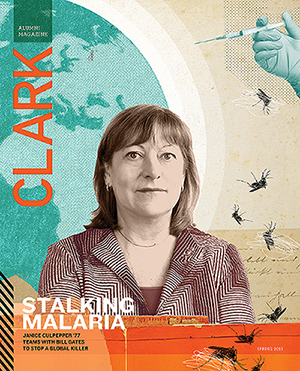

Clark Magazine

The Entrepreneur’s Journey

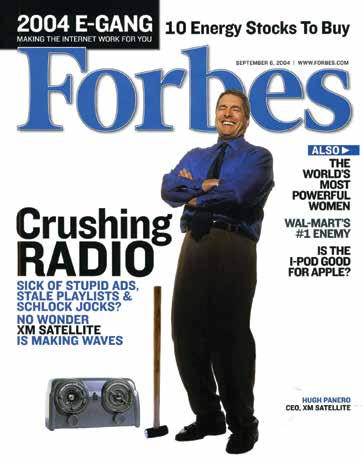

The headline on the Sept. 6, 2004, cover of Forbes magazine was hardly subtle.

“CRUSHING RADIO” it declaimed. Then the subhead: “Sick of stupid ads, stale playlists & schlock jocks? No wonder XM Satellite is making waves.”

Three images illustrated the sentiment. A boom box, a sledgehammer, and Hugh Panero ’78, then chief executive officer and co-founder of XM, rearing back and laughing … hard.

With good reason. Panero had ignited a radio revolution built on an innovative technology allowing a satellite to send a signal to a tiny antenna atop a car traveling at 70 mph and pump that car full of music, sports, and talk of boundless genres, stripes, and persuasions. He and his team not only had executed a brilliant business strategy — they’d changed the game.

Flash forward to August 2014. Forbes has assembled a list of the United States’ most entrepreneurial colleges and universities based on the number of alumni and students who have identified themselves as founders and business owners on LinkedIn. Several of the Ivys and other well-known schools are represented — the usual suspects. But nestled at number 13 among the likes of Stanford, Yale, Princeton and MIT is Clark University.”

I was pleased to see Clark on the Forbes list,” says Panero. “Look at the impressive people who have come out of the school and what they’ve done. I think it comes from a heritage of social entrepreneurship that leads to business entrepreneurship. Clarkies feel they can do a lot of things, but they also have the humanity to take into account the community they live in and the people around them.”

∞∞∞∞

As he stapled egg cartons to a wall to soundproof the studio at a Worcester public-access cable station, Clark student Hugh Panero couldn’t have envisioned his eventual path in the media world. But as the son of an architect who rehabbed neglected buildings throughout New York City, he did possess a lasting regard for the possibilities of transformation.

His internship at the station, at a time when cable television was in its infancy, opened Panero’s eyes to an evolving medium. After graduation, he did a short stint as a paralegal in Manhattan before enrolling in a series of courses about the cable television industry taught by an executive from a then-fledgling pay TV service called HBO. One of the speakers, the editor of a cable trade magazine, announced she was looking to hire reporters.

“I raised my hand, ran up, knocked a couple of people out of the way, and gave her résumé,” Panero recalls. “Then I went home and wrote an article about the class, had it typeset, and sent it to her as a follow-up. She rewarded me with a $9,000-a-year job as a reporter.”

He was in. Panero found a niche writing about the aggressive tactics major media companies were using to compete for big-city cable franchises. Soon his reporting was being quoted in The New York Times and his expertise on the topic was making him a player in the high-stakes tumult of the nation’s burgeoning cable industry. Time Warner took notice and offered him a job to help secure cable franchises around the country and especially in New York City, his hometown. He worked at the company for 10 years in a variety of positions, including vice president of marketing for the New York cable operation.

He was in. Panero found a niche writing about the aggressive tactics major media companies were using to compete for big-city cable franchises. Soon his reporting was being quoted in The New York Times and his expertise on the topic was making him a player in the high-stakes tumult of the nation’s burgeoning cable industry. Time Warner took notice and offered him a job to help secure cable franchises around the country and especially in New York City, his hometown. He worked at the company for 10 years in a variety of positions, including vice president of marketing for the New York cable operation.

“Even within an established company there are entrepreneurs,” he says. “When riskier opportunities would prevent themselves, like starting up the outer-borough cable systems, or if a new business like pay-per-view was surfacing, some people would avoid taking those risks. This was actually great for me because it would open up an opportunity for me to step in and say, ‘I have a couple of ideas on how to do that. Give it to me and let me run with it.'”

Panero eventually was lured to Denver, where he spent five years as the president and CEO of Request Television, a national pay-per-view network. With the challenge of Direct TV threatening the cable industry, he helped orchestrate the merger of Request with its competitor, Viewer’s Choice.

In 1998 he got a call from a headhunter with an intriguing question: Had Hugh ever considered the infinite potential of satellite radio?

∞∞∞∞

On Sept. 25, 2001, Hugh Panero sat in a replica of Capt. James T. Kirk’s command seat on the Starship Enterprise from “Star Trek” and pushed the button that launched XM Satellite Radio service.

The details leading to that seminal moment could fill every page of this magazine, and the next one.

Panero had joined a group that wanted to make satellite radio a reality. They just needed someone to tell them how to do it.

“I asked what the big criticisms of this endeavor are, and someone said, ‘We don’t think people will pay for radio.’ I didn’t believe that was valid. I’d basically grown up in cable, where people said nobody would pay for television. Considering the state of radio at the time, which was horrific, I believed someone would pay for a great radio service offering a number of channels and the kind of music they really wanted to hear. There was a market.”

Panero not only had to raise the billions in capital to make XM viable, he had to be satisfied that the science — which existed but was untested — would support the venture. He hit the road to get investors excited about a product that sounded vaguely space-age and even downright radical.

Sometime after XM debuted, Panero was named Satellite Executive of the Year. “In my speech I joked about the irony of me getting this award having come from the school with a library named after the father of modern rocketry,” he says, adding with a laugh, “And it was a library I tried to avoid.”

A critical stop on the road to taking XM public was talking with Wall Street’s best-known satellite analysts, and one who happened to be a fellow Clark alumnus, Vijay Jayant ’92.

“When you want to go public these satellite analysts are a very important constituency,” Panero says. “There was nothing better in our first conversation with the leading satellite analyst than to have him ask me about Spree Day.”

On another financial roadshow in Los Angeles, for a bond offering, Panero was pitching XM when he was approached during a break by a familiar-looking man. “Hugh,” the man grinned, “It’s Peter.”

“It was Peter McMillan [’79]. Here I was in total selling mode, and here was Peter stopping to say hello. We played a lot of basketball together at Clark.”

Asked to describe the process of getting XM off the ground, Panero quickly tosses out two adjectives: harrowing and exhilarating. As he and his colleagues pieced together the financing with five or six different investors, there was any number of times then and over the years when the company could have crumbled.

“One of the great joys of doing entrepreneurial company-building is starting off in a basement with six or seven people, really grunging it out, and turning it into something that’s a lasting part of the media landscape,” he says. “There were plenty of near-death experiences where the company seemed to have nine lives. As my father would say, these things build character.”

∞∞∞∞

When he was looking to find permanent headquarters for XM, Panero remembered the lessons his father — and his university — had taught him about being an agent of change in the community. During his student days at Clark, he did nonprofit community work in the neighborhoods: for Summers world, a federal program that provided services in low-income housing projects, facilities for senior citizens and other institutions; as a paralegal with Legal Aid; and with Mass Fair Share, a citizens group that worked with low-income residents.

The sum of these experiences helped inform his decision to settle in a rundown former printer’s building in an impoverished Washington,D.C. neighborhood known as NOMA, short for “north of Massachusetts Avenue.” The move was greeted with skepticism from those who knew the area’s reputation for violence, addiction and prostitution. But the federal and local governments had targeted the neighborhood for renewal with the hope that a private company like XM would step in and be the linchpin for redevelopment efforts.

Once XM set up shop, neighborhood progress followed, with the help of the construction of a new headquarters for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms and the opening of the New York Avenue Metro Station, a key component of the revitalization effort and a channel connecting NOMA to other points in the city.

“The area is unrecognizable today; it’s totally transformed,” Panero says. “It’s one of things I’m proudest of.”

“Clarkies feel they can do a lot of things, but they also have the humanity to take into account the people around them.”

The opening of XM’s headquarters was celebrated with a party featuring a performance by Aretha Franklin and tours of the company’s 50 studios. Among the guests were old Clark friends like John O’Connor ’78, a Clark trustee, who had stressed to Hugh the importance of community involvement, and former roommate Leland Stein ’78, who worked at radio station WCUW and would scold Hugh for forgetting to put his records back in their sleeves.

“I can honestly say the Clark contingent was more impressed with me putting XM in a tough neighborhood than with what I was trying to do with the company in satellite radio,” Panero says.

The launch of XM was scheduled for September 12, 2001, with a national ad campaign ready to roll.

September 11, 2001, would change all that.

“In our tech headquarters, we had an enormous television screen, and we watched the planes hit the World Trade Center. Then we looked out the window and could see smoke billowing from the area of the Pentagon located only six miles away. We were left trying to figure out how to deal with what was happening from a business standpoint while at the same time calling home to check on our families.”

Panero postponed the kick-off and scrapped the company’s “Falling Stars” ad campaign, which featured celebrities like B.B. King and David Bowie plummeting from the sky. The imagery, once comedic, was now all wrong.

Otherwise, Panero remained undaunted. A few weeks later XM was launched from the Star Trek-inspired control room and took off like one of Goddard’s rockets. News accounts from the time detail extraordinary growth as XM added millions of subscribers and struck deals with automakers like GM, Honda and Toyota to install XM radios in their cars. The company went to war against its competitor, Sirius Satellite Radio, to land high-profile content deals with Major League Baseball, the National Hockey League and Oprah Winfrey (Sirius countered with the National Football League and Howard Stern).

“It had elements of a boxing match,” Panero acknowledges. “Sirius was our direct competitor, but we were also trying to differentiate ourselves in an environment that included FM radio and the newly launched Apple iPod.”

XM and Sirius, after almost a decade of competing head-to-head, eventually decided to merge companies due to market conditions and the fact that by combining their duplicate infrastructures they could create a much stronger company to compete against free traditional radio and new digital music offerings. The companies began discussing a merger in 2006, and in July 2008, after a lengthy regulatory process, the deal to create SiriusXM was finally completed. Today, the combined company has more than 27 million subscribers and is built into most new cars sold in the United States.

∞∞∞∞

Panero left XM in 2007 and joined New Enterprise Associates, a top venture capital firm specializing in technology, where he helped them find, manage and strategize around newly hatched companies like Buzzfeed, among others.

Today he concentrates his efforts on a swath of business and philanthropic endeavors. Panero owns Yellow Brick Road Ventures, which consults and invests in a variety of new media companies like HopOn, whose app offers a simplified and social way to book travel arrangements, similar to what Spotify has done for music. Another company, Alarm.com, connects a person’s alarm system and video surveillance to his or her smartphone. Panero also sits on the board of Philo, which provides broadband entertainment services to college campuses.

Close to his heart is his work with CollegeTracks, a Maryland nonprofit that helps low-income minority high school students get into and succeed in college.

Then there’s the organization he chairs, Hope for Henry, which finds ways to improve the lives of children undergoing cancer treatment in two Washington, D.C., hospitals. Hope for Henry routinely brings in professional athletes and costumed superheroes to meet young patients in the pediatric cancer care units. Panero’s commitment to the cause is grounded in the ordeal his own family endured in 2001 when his wife, Mary Beth Durkin, was diagnosed with an aggressive form of leukemia that required a lifesaving stem cell transplant. (She is in good health today.)

“We spent a lot of time in hospitals and saw very young children going through the same challenging procedures my wife was going through,” he remembers. “We’d be stunned by what they had to deal with at such a young age, and we wanted to be part of an organization like Hope for Henry that did something to help make their lives a little bit easier. There’s nothing more gratifying than going into a hospital where a child is getting chemotherapy and watch him light up when Batman walks into the room.”

When considering his career, Panero is not shy about crediting the influence of Clark University. He cites the legacy of creativity and independence that helped land him on the cover of Forbes, and which gets his alma mater mentioned in the same breath as the Stanfords of the world.

“It’s fascinating to see the entrepreneurs who have come out of this place — people like Ron Shaich [’76] and Matt Goldman [’83, MBA ’84],” he says. “And look at the variety of companies — a satellite radio company, Panera Bread, Blue Man Group.

“Clark’s culture has always been one of entrepreneurship. If you have a good idea and the risk tolerance to go out and try it, your effort should be reflected in the civic things that get done and in the business things that get done. I find that very cool.”