Archivist Fordyce Williams receives periodic requests from people inquiring about a family member’s time at Clark University.

“Can you send me the yearbook photo of my grandfather?” they may ask. Or, “Did The Scarlet review the student play my mother directed?”

Last October, Williams took a call from a colleague at a Boston-area college asking her to locate the dissertation of a man who had earned his Ph.D. in chemistry from Clark in the early 1960s. The request came from the man’s son, with a somber advisory. His father was dying. The dissertation involved a detailed study of ragweed pollen, and one last time the ailing author wanted to hear the scholarly words he’d written more than 50 years earlier. His son would read them to him. While the specifics of the query were uncommon, the spirit driving it was not.

“People are very curious to know the footprint their family members left here,” Williams says.

Those who think of a university archive as a dusty repository of the past with little relevance to the present need only stop by the Clark University Department of Archives and Special Collections, housed in the Goddard Library. Yes, these rooms are anchored in the long ago, their foundation built upon the astounding collections of the institution’s founder, Jonas Clark, and his wife Susan. But they are also an ark inside which is preserved much more than dry fact — here reside generations of connection, lore and legacy.

This year, the 200th anniversary of founder Jonas Clark’s birth, is perhaps the most appropriate time to consider and celebrate the hidden treasures at the heart of the Clark campus, the collections that help reveal the soul of this place. This place of footprints.

History in a butcher’s wrapper

Williams, since 2009 coordinator of Clark’s Archives and Special Collections, takes a professional’s care to distinguish between these two entities.

Archives, she explains, contains official materials generated by the University over the course of its existence, like minutes of trustee and committee meetings; student applications, transcripts, master’s and dissertation theses; personnel records, and the personal papers of Jonas and Susan Clark, where one can read an entry from abolitionist Frederick Douglass in Susan’s autograph book.

Special Collections is a repository for donated material— which may or may not have a prior connection to the University — dating all the way back to a 4,000-yearold Babylonian clay tablet. It was established in 1969 with a dedicated curator, Paul Clarkson ’25, in the newly built Goddard Library. University Archives was established three years later on the urging of professor of history and geography William Koelsch, M.A. ’59, who was determined to write a history of Clark.

“You couldn’t do an adequate history without there being an adequate archive, of which there was practically nothing,” he notes.

In 1972 Koelsch was appointed Clark’s first official archivist. Forty-plus years later, he vividly remembers the effort it took to scour the campus for relevant materials and relocate them to the Goddard Library.

“It was a scramble,” says Koelsch, now a professor emeritus. “You’re suddenly going into closets and basements, and finding all kinds of stuff.”

Records from a University treasurer who had died in 1924 were found unopened on a shelf, still wrapped in the original butcher’s paper. Decades of student records were stored in the unfinished basement of the Downing Street administrative building, where, Koelsch says, many of the staff refused to venture because it was infested with mice and paper-loving bugs. An exterminator had to be called in before the documents could be transferred to their new home in Goddard. The basement was treated on a Saturday, and the smell that lingered the following Monday was too intense for the Dean of Students office to be occupied that day. Koelsch catalogued and shepherded the collection for a decade. In 1982 he passed the baton to his assistant archivist, Stuart Campbell. With an archive now at his disposal, Koelsch was able to pen “Clark University, 1887-1987” in time for the University’s centennial celebration.

Jonas, Susan, and Thomas Jefferson

When Goddard Library was completed in 1969, Jonas and Susan Clark’s art collection, books and papers were relocated from the third floor of the old library in Jefferson Hall to an area in Goddard where they became the kernel of Special Collections. Moving rarely goes smoothly, and Tom Dolan ’62, M.A.Ed. ’63, then senior vice president, recalls walking along Downing Street behind Jefferson Hall where workers were using a chute to channel discarded material from the old library down into a dumpster. Dolan noticed a large painting next in line for disposal. He called a temporary halt to the proceedings and rescued a beautiful landscape titled “Snowing” by local painter Joseph H. Greenwood. The painting, now safely displayed in Harrington House, had been acquired in 1913 using funds Jonas Clark had left to the University.

“It was just a lucky day for me and for Clark,” he says.

Some paintings were displayed around campus, including at Anderson House, home to the English Department. Unfortunately, at a time when security was more lax, several of these were stolen. Koelsch recalls that, some years later, President Mortimer Appley received an anonymous note from the (possibly remorseful) thief with a key to a bus station locker where one of the missing paintings was recovered.

During her time at Clark University, former art history professor Bonnie Grad made an intensive study of the Clarks’ painting collection, which resulted in a 1987 Worcester Art Museum exhibition of many of the works. The paintings of landscapes and genre scenes are representative of Victorian taste in the 1860s-70s, she says. Grad says her research into the collection gave her a tremendous appreciation for Jonas and Susan.

“I fell in love with the Clarks. I really got to know them as people and came to feel they were very special,” she says, noting their humility, lack of pretension and exemplary social values.

Grad, who in the course of her career served as a research assistant during the renovation of the rotunda at the University of Virginia, compared the couple to the founder of that institution. “During my 40 years of research in the art world, it was the Clarks and Thomas Jefferson whom I came to respect most as human beings.”

Dear Dr. Freud …

Archives accrues materials on an annual basis, creating a narrative thread of Clark history. Academic catalogs reveal evolving sensibilities in course curricula over the decades. Yearbooks prior to World War II document an all-male undergraduate student body, and several large ledgers record the details from the once-required physical examinations of those student bodies. Issues of the Clark News (predecessor to The Scarlet) make frequent mention of a now-defunct social event known as a Boheme. Black and white photographs capture other lost Clark traditions like the annual steeplechase, rope pull and greased pig race, and reveal the University’s state-of-the-art scientific laboratories from the turn of the last century. Architectural renderings of early campus buildings occupy slots in flat files. Grainy film footage from the 1950s provides a window on campus life. The Archives also holds realia (non-paper materials) like men’s and women’s freshman beanies, letter sweaters, athletic uniforms, fencing foils, even wooden dumbbells once used in calisthenics classes.

The letters of Clark’s first president, G. Stanley Hall, to Sigmund Freud are of particular interest to historians of psychology, and have been consulted by researchers from as far away as Japan. Special Collections, more eclectic but no less intriguing, shelters a number of important works.

Preeminent are the 194 boxes constituting the Robert Goddard Collection, including the rocket pioneer’s notebooks, patents, correspondence, his wife’s papers, and paraphernalia like his gyroscope and rocket bits and pieces (among them, a nose cone).

A leather-bound, 20-volume set of “The North American Indian” by early 20th-century photographer and ethnographer Edward Curtis, with a forward by Theodore Roosevelt, is one of only 500 printed. The set features detailed observations, in words and oversized sepia photographs, of Native American tribes then living west of the Mississippi, and speaks heart-wrenchingly of cultures in the twilight of their existence.

Another uncommon collection is a set of approximately 1,200 miniature books (no larger than three inches). The smallest, one half-inch square in size, comes equipped with its own tiny magnifying glass. Another, an autobiography of Robert Goddard’s early life published by Achille St. Onge of Worcester, accompanied astronaut Buzz Aldrin to the moon and back.

Former Archives and Special Collections coordinator Mott Linn, M.P.A. ’03, now head of Collections Management, is particularly enthusiastic about two other sets of materials. One is a series of books chronicling geographical explorations, notably to the Arctic and Antarctic, spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The books, many of them first editions, feature first-person narratives like the harrowing “Worst Journey in the World: Antarctic, 1910-1913,” about Robert Scott’s fatal attempt to reach the South Pole, written by expedition survivor Apsley Cherry-Garrard.

“If you want to study explorations,” says Linn, “you could do a really good job starting here.”

Linn also is partial to the World War I Collection. In 1914, then-University librarian Louis Napoleon Wilson proposed that Clark begin collecting material about The Great War. An immense effort was put into gathering printed materials published in a variety of languages: fiction and nonfiction, newspapers and posters, even comic books. Because of the dire economic conditions at that time, many were printed on cheap, high-acid paper,now brown and brittle with age.

Among other treasures are papers related to three well known authors with ties to Worcester. One-time Worcester resident Esther Forbes earned fame for her Newbery Award-winning novel “Johnny Tremain,” and her Pulitzer Prize-winning “Paul Revere and the World He Lived In,” both published in the early 1940s. Worcester-native Olive Higgins Prouty caught the attention of Hollywood with her novels “Stella Dallas” and “Now, Voyager,” both of which were made into films starring, respectively, Barbara Stanwyck and Bette Davis. Correspondence between Poet Laureate Stanley Kunitz and the Stockmal family, who purchased the Worcester house he grew up in, is also available for study.

Family ties

Dorothy Mosakowski, the first person appointed to head the combined Archives and Special Collections, says she loved every minute of her time there. She describes it as a bustling place.

“People think that places containing archives and rare books are quiet,” she says. “But it was not quiet. Ever.”

That hasn’t changed. Williams fields all manner of requests from Clark employees, students and alumni, outside scholars and members of the general public. Typically she’ll disappear into the climate-controlled storage room and reemerge with the sought-after artifact.

“I really enjoy the variety to my days,” she says.” Everyone who comes in or emails is looking for different things. Finding those items for them continually teaches me more about the collection.”

As with the man who sought out his father’s dissertation, many of those visiting or sending queries are researching a family member. A university archive might seem like an odd place to conduct genealogical research, but it contains many kinds of documents that provide relevant information. Yearbooks, publications by student clubs and organizations, student newspapers and literary magazines, master’s theses and doctoral dissertations are all sources, not just for University history, but for the lives of those who once made up the Clark community.

A daughter of a Clark alumnus who had died when she was young came to Archives to learn more about the place her father had talked of so often. Another time, a man from China sought information about his grandfather, the famous poet Hsu Chimo, who studied at Clark during the University’s early years.

Battered, beautiful books

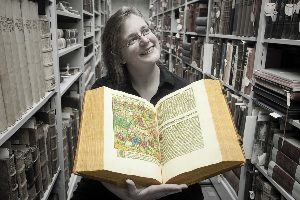

Meredith Neuman, professor of English, clearly qualifies as a power user among the faculty who integrate Archives and Special Collections into their teaching. Jonas Clark’s book collection features heavily in her archival research course, the first half of which traces book history and the development of print culture in Europe and the United States. Neuman describes the collection, whose earliest item is a Bible from 1275, as “a wonderful hodge-podge.”

“In it you can identify certain collecting trends, but you also get the sense Jonas Clark was collecting everything he could,” she says. “Because it’s such an eclectic, and in some cases a very battered, collection, it’s ideal for studying book history. We talk about bindings, we talk about clasps, about how people stored books. We talk about the book as a physical object that leaves clues about how it has been used historically.”

Neuman, who has trained at the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia, includes as part of her course weekly, hands-on lab sessions where each student analyzes the physical structure of different books in the collection.

In part to protect the Jonas Clark books from unnecessary wear and tear, Neuman is gradually assembling a separate, dedicated teaching collection of 17th-, 18th- and 19th-century books. The endeavor is being supported with funding from the Friends of the Goddard Library.

“It’s wonderful to collaborate with library staff on projects like this,” she enthuses. “It’s really been a partnership.”

Junior Nick Cotoulas found his passion in the Archives and Special Collections, completing a LEEP research project that drew on Clark’s World War I collection. He focused on the corps of approximately 18 Clark University students who manned a volunteer ambulance unit in France, a story he unearthed in the boxes containing the letters, dog tags, and uniform patches and stripes of one-time Clark student Oliver Cook. Cotoulas eventually expanded the scope of his research, which culminated in the exhibit “Clark University’s WWI Collection: Reflections on the Past,” on display in Goddard Library.

“What draws me most to this work is the physical connection to the material; working hands-on,” he says. “When you read letters from people long ago about issues that are very similar to what you’re experiencing, it makes you realize the closeness that we have to the history. “The Archives has a certain serendipity to it. There’s a mysterious quality where the Archives determines the project and what the researcher gets out of it.”

Cotoulas, who is assisting on a project to catalogue Jonas Clark’s books, recently spoke at the Hubbardston (Mass.) Library as part of its bicentennial celebration of Clark’s birth. A native of Hubbardston, Jonas Clark founded and designed the library and donated many books for its shelves. Cotoulas is excited to be exploring Jonas Clark’s volumes.

“I know I’m going to find things that I’ve never seen before,” he says. Fordyce Williams and all the gatekeepers of Clark’s history offer assurance that anyone planning to visit the Archives and Special Collections can make the same claim.

Photography by Steve King

This story appeared in CLARK Magazine, spring 2015