When Malcolm X came to Clark

What happens when you dial Malcolm X’s phone number?

He picks up.

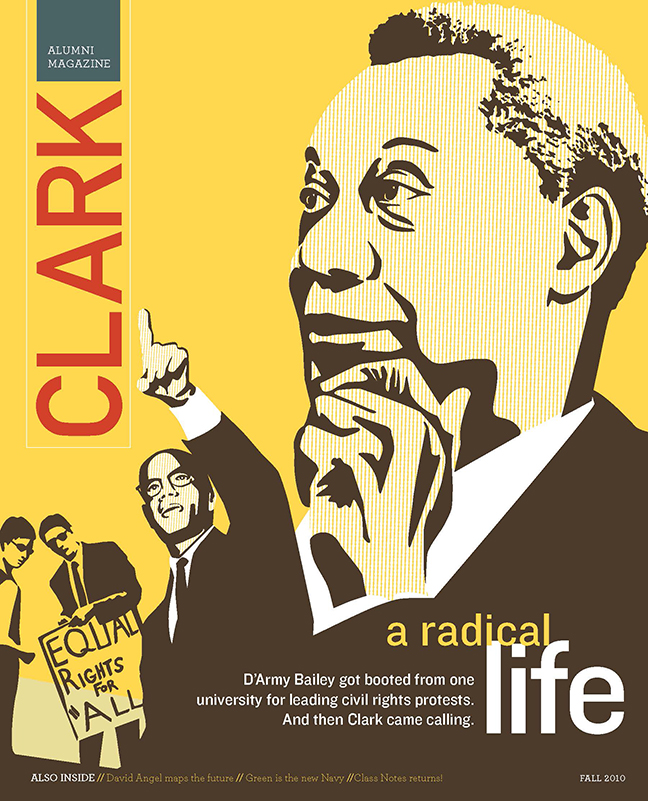

That was the shocking truth for D’Army Bailey, when in the spring of 1963 he called the Black Muslim leader with an offer to speak at Clark. No secretaries, no middlemen, just Malcolm on the other end of the line.

This was no minor request. Malcolm X and his “by any means necessary” philosophy toward achieving racial equality had unsettled much of America, white and black. But Bailey embraced the notion of bringing a healthy dose of controversy to campus and shaking up the status quo in the process.

Not everyone was enamored with the idea of Malcolm X speaking on campus. Members of the Worcester Student Movement board of advisers objected, with the chairman threatening to resign if Bailey didn’t cancel the speech. The board insisted that rather than give Malcolm X his own forum, he instead debate a civil rights leader proposing peaceful resistance.

Malcolm was intrigued by the suggestion, though he insisted he would only participate if his opponent was Martin Luther King.

King’s people declined the offer, but Malcolm agreed to speak anyway. Bailey calmed the board by pledging to bring in a more palatable speaker at a later date. During a recent interview on the Clark campus, Bailey pointed to two trees where he’d hung a banner announcing Malcolm X’s impending arrival. One night the banner was torn down. Bailey got a tip that some students had removed it and carried it to their apartment. He and some friends confronted the students, advising them to turn over the banner or there would be trouble. It was returned, and re-hung.

King’s people declined the offer, but Malcolm agreed to speak anyway. Bailey calmed the board by pledging to bring in a more palatable speaker at a later date. During a recent interview on the Clark campus, Bailey pointed to two trees where he’d hung a banner announcing Malcolm X’s impending arrival. One night the banner was torn down. Bailey got a tip that some students had removed it and carried it to their apartment. He and some friends confronted the students, advising them to turn over the banner or there would be trouble. It was returned, and re-hung.

On April 11, Bailey ushered Malcolm X to appointments with the Worcester Telegram editorial board and a radio interview.

“He savored the experience,” Bailey recalls. “He was like a cat preying on a mouse. The editors thought they could trap him, but Malcolm was so self-confident in his beliefs. He wasn’t mad, wasn’t hostile, he was just firm with what he was saying. He could smile sitting at that table.”

The crush of people in Atwood Hall that evening seemed to shrink the room — there were students and members of the public, a strong representation of black audience members who’d traveled from as far as New Haven, Black Muslims selling copies of the newspaper Muhammad Speaks, and security guards and police officers patrolling in response to threats of violent retaliation against the Muslims.

“It was an electric atmosphere,” Bailey remembers. “Malcolm was energized by this young, receptive audience. It doesn’t mean that they believed what he believed in, but they were fascinated to have this man here to talk to us … and he wore them out. He was incisive, he was unforgiving, he didn’t back down.”

Clearly. In his closing statements, as Bailey records them in his memoir “The Education of a Black Radical,” Malcolm X threw down the gauntlet:

“The time is up for the oppressor, the end of time has come for whitism and colonialism. The white man is on the way out. … We have reached the stage where we no longer think you are capable of treating us right. You do not have it in your hearts. We are turning to God.”

Malcolm later attended a reception in a student lounge, where he quietly answered the students’ questions. In this intimate setting, Bailey was struck by the man’s controlled demeanor so soon after issuing his fiery pronouncements from the Atwood Hall stage.

The evening concluded at Bailey’s apartment, where he and Malcolm X chatted about the day’s events.

“At about midnight, he charged me $75 for his expenses and I paid him,” Bailey recalls. “And then he disappeared into the night and back out of Worcester.”