It began with a knock on the door.

It began with a knock on the door.

Mugrditch Nazarian, a merchant in the city of Mezre, was roused in the middle of the night by Turkish gendarmes who said they wanted to make some immediate purchases at his store. Things quickly turned ugly, and Mugrditch was dragged from his house in his pajamas.

It was the last time his family would see him.

No one ever learned Mugrditch’s fate. Some said he was taken a few miles out of town and shot; others believed he was among those who were imprisoned in Mezre and exposed to inhuman tortures so unbearable that he and the other prisoners poured the kerosene from the jail lamps onto themselves and ended their lives as human pyres.

The year was 1915, and the Ottoman Empire had commenced with the systematic annihilation of Armenians and other Christians who were deemed enemies of the Muslim state. The men were the first victims, beginning with 250 unsuspecting Armenian intellectuals and leaders in Constantinople who were rounded up on April 24, imprisoned, tortured and killed. From there, males over the age of 15 were routinely herded into the streets, marched outside the city limits, and shot to death on lonely roads.

Women, children and the infirm were deported — hundreds of thousands of refugees driven over the mountains and into the desert under the whips of Turkish soldiers.

Women, children and the infirm were deported — hundreds of thousands of refugees driven over the mountains and into the desert under the whips of Turkish soldiers.

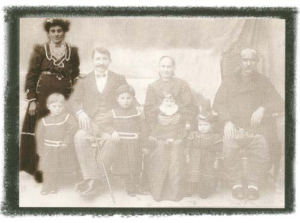

Among the deportees were Mugrditch Nazarian’s pregnant wife, Varter, and their six young children. The family fled Mezre with the hope of reaching safety in Aleppo, Syria.

Only Varter would survive. Her six children died on the journey, some brutally murdered. She gave birth along the trail and the infant perished as well.

Years later Varter found her way out of the storm and to America. Whether she found peace is another story.

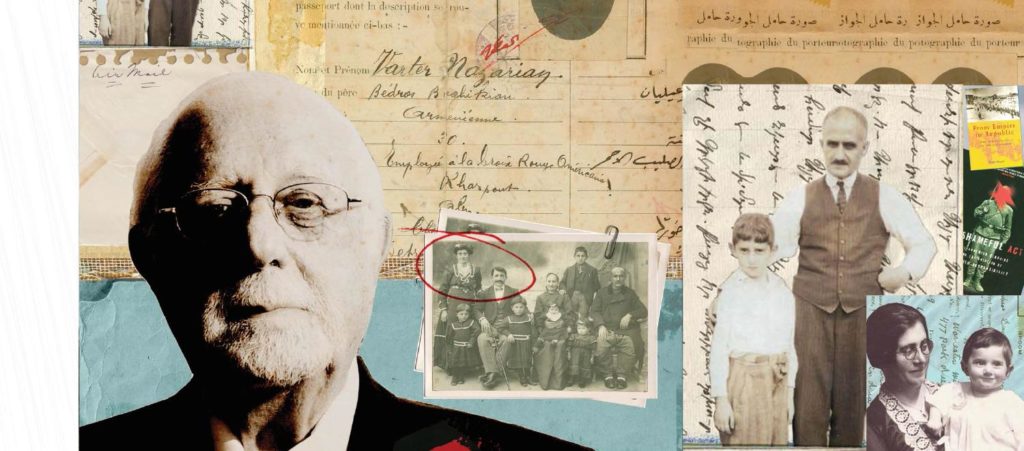

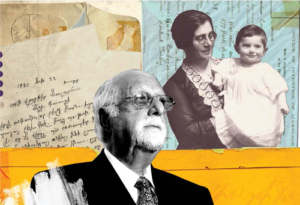

Dr. H. Martin Deranian ’47 sits in his living room in Shrewsbury, Mass., thumbing through a black binder at least six inches thick that chronicles Varter’s life. In faded photographs, some a century old, she looks into the camera lens with a curious half-smile — in one she is clearly pregnant, clasping the hand of the dashing Mugrditch. Carefully placed in the binder’s plastic sleeves are her 1920 passport from Aleppo to the United States, still in one piece but as fragile as late-autumn leaves, and heartfelt letters, meticulously penned in Armenian handwriting, to the Worcester man she would eventually marry.

Varter is Martin’s mother. She died when he was nearly seven years old, never having spoken to him of her past sorrows. Such a thing was unthinkable.

In 1966, Deranian contacted a minister who had served at one of the way-stops in the Turkish city of Urfa during the Armenian deportation, and he convinced the man to interview an elderly woman in Fresno, Calif. She had been good friends with Varter in Turkey and had experienced her share of hardships during the deportation. Through this first-hand account, the minister compiled an intimate history of Varter’s life.

The details of her ordeal were punishing to learn, but necessary. “I had to know the truth,” says her son. Corroborating the friend’s recollections with published accounts of the events in Turkey and the road to Aleppo, Deranian produced an unvarnished biography of his mother titled “The Wailing Well.”

“There is no vocabulary to describe what happened during this genocide; there is no lexicon,” says Dr. Deranian, now 91. “If I captured my mother’s story, traumatic as it was, I felt I should do that. I didn’t want to end my time on earth without addressing this issue.

“And to imagine my alma mater, Clark University, has become the center for the study of the Armenian Genocide is just too much to hope for. It almost seems meant to be.”

The Robert Aram ’52 and Marianne Kaloosdian and Stephen and Marian Mugar Chair in Armenian Genocide Studies at Clark University was the brainchild of the late John O’Connor ’78, a former Clark trustee, and his wife, Carolyn Mugar. Speaking at the 2013 Clark Commencement, Mugar recalled her grandfather’s migration to Worcester in 1890 to work in a wire mill. He returned to Armenia, married, and left for the United States in 1906 with his wife and three children nearly a decade before the carnage began.

“I give my grandfather huge credit not only for having the wisdom as such a young man to see ahead, but also for having the courage to act on that wisdom,” Mugar told the audience. “Had he stayed in Armenia, he and his family might very well have perished along with a million and a half other Armenians in the genocide of 1915. My grandfather took action — took a risk — and came here where his family found safety and a future they could not have imagined in their homeland.”

John O’Connor was very proud of his Irish heritage, Robert Kaloosdian recalls, but “he proudly proclaimed himself an ABC — an Armenian by Choice — who made it his purpose in life to establish a chair for the study of the Armenian Genocide and history at Clark. John was a charismatic leader, very bright, and one who inspired others to act.”

With a lead gift from John and Carolyn, and additional fundraising by Kaloosdian and Tom Dolan ’62, M.A.Ed. ’63, who was then vice president of alumni affairs and development, a total of $2 million was raised, and in 2002 the chair in Armenian Genocide Studies at Clark became a reality.

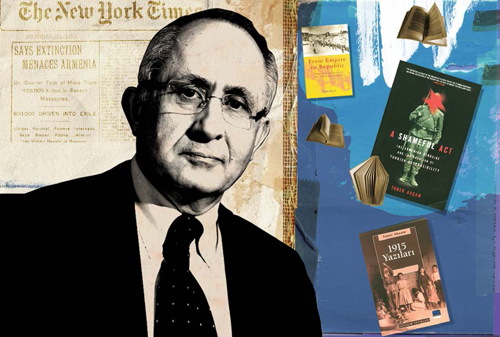

Taner Akçam, Ph.D., is breathing a little easier these days. In early August, the Turkish court sentenced members of a secret cabal of military and political operatives, codenamed Ergenekon, to heavy prison sentences, some of them for life. For years the ultra-nationalist group had conducted a series of assassinations and other terrorist acts as part of a plot to overthrow the Turkish government. Among their targets were scholars, journalists and activists who agitated for democratic ideals and urged Turkey to acknowledge its past human rights abuses, most notably the Armenian Genocide, a savage chapter in its history that Turkey has never officially recognized.

Akçam was on their hit list.

For years he couldn’t travel to his native Turkey for fear of being gunned down in the street, like his good friend Hrant Dink, a journalist who in 2007 was assassinated in Istanbul for his outspoken criticism of Turkey’s institutionalized denial of the genocide and diaspora. Akçam, the holder of Clark’s chair of Armenian Genocide Studies since 2008 (succeeding Simon Payaslian) and the author of 10 books detailing Turkey’s culpability, has never shied from taking hard stands against his home country. By the time he arrived at Clark, the Ergenekon had already left a trail of bodies throughout Turkey, and by 2010 Akçam was seeking protection from the FBI and local police.

His outspokenness always came at a price. At a 2006 lecture and book signing in New York, Akçam was heckled and then attacked by a group of Ergenekon-sponsored nationalists who were apprehended by security. Ergenekon members also waged an online smear campaign against Akçam, vandalizing his Wikipedia page, issuing threats against universities that invited him to lecture, and denouncing him as a terrorist who plotted attacks against American citizens. The latter charge got him stopped and questioned at the Canadian border.

Today, he speaks of two overriding emotions from that time: fear and anger. The fear of death and the anger that began simmering in 1988 when he was a research assistant at the Hamburg Institute for Social Research in Germany and contributed to a report titled “History of Violence in Ottoman Turkish Society.” It was the first time he’d heard of the Armenian massacres, a topic never taught during his school years in Turkey.

“It’s a very bad feeling to learn you were deceived throughout your history,” Akçam says during an interview in his office in the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. “Even more upsetting is how the state reacts to individuals who openly talk about this. As a scholar, as with any individual, you use basic freedom of thought to write on a subject because you know it is important and true. The Turkish state attacks you, tries to strangle your efforts from the very beginning, declares you a traitor. This creates an anger in you. The way the state treated me is what really kept me working in this field.”

Akçam was arrested in the late 1970s in connection with articles he’d written in a student journal urging human rights reforms and an end to the persecution of Kurds in Turkey. He was sentenced to eight years and nine months in prison and served a year in jail in the city of Ankara before he and other political prisoners hatched an escape plan. They were being kept in an old horse stable, and tunneled their way into an adjoining building. Once inside, they tied bed sheets together and dropped down into the street. “Like in a movie,” Akçam grins. He gained political asylum in Germany, but was exiled from Turkey for 16 years.

Emaciated, nearly naked, and so desperately thirsty she was forced to drink urine, Varter Nazarian staggered through the desert with the two of her young children who still lived. At one point, to escape detection from the soldiers, she and the children descended into a dry well and hid for two days without food or water. As Martin Deranian recounts in “The Wailing Well,” a passing Arab called down to them to come out of the well. Varter insisted that he pull the children out, but the man convinced Varter to climb out first so the two of them could assist the children, who were too small to manage the climb alone.

Instead, once Varter emerged from the well, the man forcibly abducted her. “He was totally deaf to her appeals for her children left in the well,” Deranian writes. “Their echoing voices cried after her, ‘Mother, Mother!’ These infants’ cries haunted and tormented her the remaining days and dark nights of her life. The dry hole became Varter’s wailing well.”

Varter would later escape from the man’s home and make her way to Urfa, where she was overtaken by a Turkish soldier and forced into servitude. With the aid of an Armenian clergyman and a Swiss missionary, she fled with a German convoy and found safe passage to Aleppo. There she remained for several years, working on behalf of Near East Relief, the American Consular Service and the American Red Cross to help fellow deportees through their ordeal. Peering into the face of every child who arrived in the city, Varter maintained faith that some of her children had managed to survive. The mix of hope and uncertainty kept her anchored in Aleppo, ever on vigil.

Over time, the notion that she would ever reunite with her children faded. Her immediate family was wiped out, and only three members of her extended family had survived the brutal death march. In the district where she had been born, where there had been 200,000 residents, only 15,000 remained by early 1917. In July 1920, Varter emigrated to America, alone.

Martin Deranian wrote a paper in 1941 during his freshman year at Clark titled “The History of the Armenians in Worcester.” His professor gave him a mediocre grade and insisted he should have done more research.

He eventually did. In 1998 he wrote “Worcester is America,” a hardbound book that chronicles in exhaustive detail the Armenian experience in Central Massachusetts. He includes the story of his own family, including that of his two grandfathers, who came to the U.S. to work in the wire mills in the late 1800s, returned to Armenia, and were killed in the genocide. He also writes about Varter, who married his father, Mardiros Deranian, a Worcester grocery shop owner, on November 12, 1921, in the Church of Our Saviour, the first Armenian church in America. She gave birth to Martin in August a year later.

He grew up within walking distance of Clark University, earned his degree, attended dental school at the University of Pennsylvania, and served as a military dentist during the Korean War. Dr. Deranian then built a thriving practice in Worcester while raising a family. Despite these responsibilities, keeping Varter’s memory alive in the context of the “forgotten genocide” remained a passion.

“My mother was very strong, very spiritual, and she carried her Christian faith with her,” he says. “I believe she would have wanted me to do the things I’m doing. I felt I should speak for those little children — my half-brothers and sisters. I’m 91, and I could walk away, but I don’t choose to. I’m a Clarkie.”

Clark’s connection to the Armenian community dates back to the turn of the last century, when the immigrant mill workers in Worcester and the surrounding towns began sending their children to the University, says Robert Kaloosdian. “These families did not have much, but they always had a love and deep appreciation for education.”

Clark was an accepting place, and the Armenian presence grew strong over the years. Kaloosdian easily recites the names of distinguished alumni of Armenian heritage like Dr. Vernon Ahmadjian ’52, M.A. ’56, who would become a beloved Clark professor and renowned authority on lichens; famed journalist Ben Bagdikian ’41, former editor of The Washington Post; and District Court Judge Sarkis Teshoian ’58.

As a student, Kaloosdian, a retired Watertown, Mass., attorney, launched an Armenian Club at Clark, served as a fraternity president and earned a varsity letter rowing crew. His involvement in helping create and maintain the chair in Armenian Genocide Studies at Clark is bred from his deep love for the University and his desire that it remain in the forefront of keeping this area of study vital and urgent.

There is a personal motivation as well.

Kaloosdian’s own father was orphaned at age 15 during the first year of the genocide, his parents and brother killed along with numerous members of his extended family.

“The genocide was so horrific most parents, including mine, did not disclose the details to their offspring. They were too personal, too horrific for youngsters to know or understand,” he recalls. “Amongst our extended family were survivors: women whose experiences damaged them psychologically for life; women who had children ripped from their arms and killed in front of them. There were others who were taken as concubines or sold to be ‘wives,’ servants or farmhands.

“These were not subjects that could be discussed while dining or in living rooms. Briefly, I knew that horrible things happened, but with virtually little or no specificity until on my own I searched the literature to learn what occurred to the Armenian people and nation from 1914 to 1923. It was not a pleasant journey.”

The first genocide of the 20th century served as a prototype for other mass exterminations, especially the Holocaust of the Jewish people under Hitler, he says. Not only were 1.5 million Armenians killed, but more than 3,000 churches, schools and countless monuments were destroyed. Notes Kaloosdian, “It is the extinction not only of a people, but of its culture.”

Taner Akçam does not back down from a fight.

He has engaged in heated arguments on Turkish television with Armenian Genocide deniers, published open letters to the Turkish prime minister urging recognition of the massacres, and continues to write books and newspaper articles telling the truth about his own country’s crimes against humanity. One columnist dubbed him “the conscience of Turkey.”

In October 2011, the European Court of Human Rights found that Turkey had violated Akçam’s freedom of expression due to a controversial law known as Article 301, which made it a crime to “insult Turkishness” and was used to prosecute writers and other intellectuals. Akçam argued that Article 301 directly led to the assassination of Hrant Dink. “Turkey should learn that facing history and coming to terms with past human rights abuses is not a crime but a prerequisite for peace and reconciliation in the region,” Akçam said at the time. Article 301 has since been defanged to the point where it can’t be invoked without special permission from the Justice Ministry, an unlikely occurrence. He says that Turkey can no longer pursue a legal case against someone for raising the issue of the Armenian Genocide.

Other than the prospect of physical retaliation, one of Akçam’s greatest foes has been apathy. He notes that Dink’s killing sparked demonstrations in the streets, and he believes that public sentiment now tilts in favor of Turkey recognizing the genocide. But he marvels at the “conspiracy of silence” the subject engendered among the people in the preceding years, particularly in the 1990s.

“There’s a fatalism in our society, especially toward history. Nobody cared about it. I even have good friends who told me, ‘It was a hundred years ago. Let it go.’ This bothers me more than the threat of physical attack.”

“There’s a fatalism in our society, especially toward history. Nobody cared about it. I even have good friends who told me, ‘It was a hundred years ago. Let it go.’ This bothers me more than the threat of physical attack.”

Even Turkey’s hardline stance has become more nuanced, he says. “They don’t take the extreme denialist position as in the past. It’s a new form of denialism, by saying there are ‘diverse opinions’ on the subject and room for ‘reasonable doubt.’ It’s just a different approach of presenting the same argument.”

He is hopeful, but not overly optimistic, that the United States will officially acknowledge the genocide, an action the government has been unwilling to take because it could damage its relationship with Turkey, a strategic ally in the Middle East. To do so would be more than symbolic, he says. If the U.S. government recognizes the 1915 genocide, it will likely launch several court cases against the Turkish state and Turkish companies connected to the century-old crimes.

For now, Akçam is focused on shepherding four Ph.D. candidates in Armenian Genocide studies, and lauds Clark as an exemplar for creating the only endowed chair in the Americas in this field.

“The connection between the University and the Armenian community is very important,” he says. “We use and understand their pain for a broader context. Clark has been an unbelievable support. It’s a very serious thing to have a position in an American university to teach human rights and genocide. That’s something that everybody must respect.”

Steven Migridichian, president of the Friends of the Chair in Armenian Genocide Studies at Clark, agrees.

“Awareness is a great tool, and it’s important to promote and foster that knowledge among everyone,” he says. “Darfur. Rwanda. Cambodia. These events need to be brought forward. People say we shouldn’t dwell on the past, but history has a way of repeating itself once we forget.”

On May 4, 1929, while visiting relatives in Providence, Varter Deranian died when a blood vessel in her brain ruptured. She was 44 years old. Her son writes:

“When she briefly regained consciousness, she cried, ‘My children, my children!’ These were her last words. Her thoughts and her being had returned to the waterless well in the barren deserts of Turkey. Mother and children were at last reunited and the wailing forever silenced.”

Penning those words was painful for Martin Deranian, but he never expected anything less. He only wanted the truth to be told for whatever audience it may find.

“The wrath of time is upon us,” he says today. “The survivors of the Armenian Genocide are virtually gone, and my generation, who had direct contact with survivors, is getting old. So there has been the pressure of time to do what I can, and I think I’ve done that.

“Hopefully, I’ve lived a constructive life, but there are moments when I almost feel like I’m walking the route of the deportees through the desert. I’ve learned so much about my mother that she never told me. I suppose she wanted to protect me. That’s what mothers do.”

This story was originally published in CLARK Magazine, fall 2013.