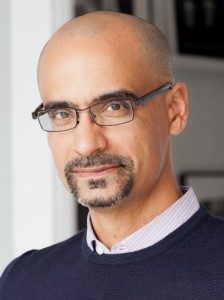

He came to Clark University on Sept. 30 to deliver the President’s Lecture, but novelist Junot Diaz quickly disabused the audience of any notion that his lecture would be like any other delivered within the walls of venerable Atwood Hall.

Eschewing the podium to roam the stage, Diaz launched into a dialogue-driven presentation in which he used audience questions to issue thoughtful, wry and salty observations on his life, his art, and the political and social forces that have shaped his identity. He also read passages from two of his books, the short story collection “Drown” and the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.”

The first questioner asked Diaz his feelings about “living on the hyphen” as a Dominican-American. “One of the strange things is that as an immigrant everyone’s always trying to put frames on what your experience is,” he said, pointing to the fallacy that immigrants are more “conflicted” than other people. “This of course isn’t true. As someone who grew up with a ton of non-immigrants, I can tell you non-immigrants are equally [bleeped] up as immigrants,” he noted, drawing a big laugh.

People of mixed heritage, Diaz said, are led to believe that they “only get one shot at the buffet” in American society and must align with a single ethnicity rather than embrace the “simultaneity” of one’s identity, which can include multiple facets that are contradictory. “Instead of being a ‘half’ of something, one might be considered a ‘double’ of something,” he said.

“It’s only a country that wants to diminish the contributions of immigrants that comes up with this stuff — that would be every country,” Diaz continued.

“I don’t know any country that’s really hyped to remind the world that they’re so not perfect that they need immigrants.”

When a student asked how he deals with writer’s block, he turned the question around and queried the student about her own difficulties with getting words on the page. Diaz urged students not to put “this incredible weight on yourself, like you’re supposed to do everything you want at beck and call.” As an MIT professor, he sees students who can be very hard on themselves. “Most of us do not learn how to drive ourselves through compassion; most of us learn how to drive ourselves through cruelty. … Have compassion for yourself,” he advised.

Diaz spoke at length about the legacy of the male-dominated society, explaining that men of color are unfairly “pathologized” over questions of patriarchy/masculinity when in fact repressive patterns are replicated worldwide. “Show me a society where the women in that society are really happy with the men’s behavior,” he said. “It’s almost like [patriarchy] has a diplomatic passport.”

On the flip side, he said, the First World “does not hold a monopoly on feminism.”

“Feminism that arises in places like the Dominican Republic — grassroots feminism, community feminism — is a very powerful, and sustained, and well-organized source of resistance, solace and rebellion against patriarchy.” Societies in general are “toxically anti-female so that every day, women have to reconstitute themselves as human.”

Diaz frankly addressed a wide range of subjects from the questions posed to him, including his use of the N-word in his books and his support of Palestine, which he acknowledged have earned him criticism. But the topic of immigration arose most frequently, with Diaz noting that the U.S. makes a concerted effort to diminish and ultimately erase the immigrant experience from its annals.

“If tomorrow we all died and all that was left of us was our television and our movies, aliens of the future would never know immigrants existed,” he said.

“In a country that despises immigrants, in a country that creates nonstop legislation to make immigrants feel not only stigmatized but also hunted; even if an individual wants to sit there and say, ‘I’ve never felt the lash of stigma,’ I can find a quorum of people in their community who would report the opposite.”

Diaz grew up in New Jersey after emigrating from the Dominican Republic, and compared the two places as being on the “margin”: the Dominican Republic, 60 miles away from the United States, and New Jersey, “one foot” from New York City — “yet they might as well be a million miles away.”

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with feeling pride about being from a margin,” he said, adding that we too often become fixated on trying to “sympathize and align ourselves with the winners.”

“What I discovered is that if you spend your time sympathizing and aligning yourself with winners, you lose solidarity with 99.9 percent of the planet.”

He described the theory of New Jersey-born artist Robert Smithson that while art is bought, sold and otherwise commodified in places like New York, London, Los Angeles and Tokyo — the “somewheres,” he called them — great art is created in the “elsewheres.”

“Only people with the marginal knowledge on the outside looking in produce the kind of art we need versus kind of art we think we need,” Diaz said. “New Jersey is the ultimate elsewhere.”