DAVID ANGEL CAN TICK OFF a slew of statistics demonstrating that Clark has made advancements as a college and university in the past decade.

But as the veteran Clark professor and administrator takes on the biggest job of his life — the University’s presidency — he is also keenly aware that the school faces some significant challenges.

As the 52-year-old British-born geographer sees it, the highest priority of his term is to make Clark both a better-known and more respected institution in the United States and throughout the world.

“I sense that the Clark community feels good about what we stand for as an institution,” says Angel, during an interview in New York City. “What alumni and students are looking for is the leadership to increase the visibility and the reputation of the school.

“That’s my charge and I have some ideas on how to do that,” he adds.

Central to Angel’s effort is the establishment on campus of “Liberal Education and Effective Practice,” or LEEP. The program couples a liberal-arts curriculum with additional training and experiences outside the classroom designed to make Clarkies better equipped to deal with the challenges of professional life once they graduate.

Elements of the program “will be rolled out like a carpet,” starting with this fall’s first-year class, he says.

As the soft-spoken Angel sees it, “Clark has the opportunity to be a thought leader around the future of liberal education in this country.”

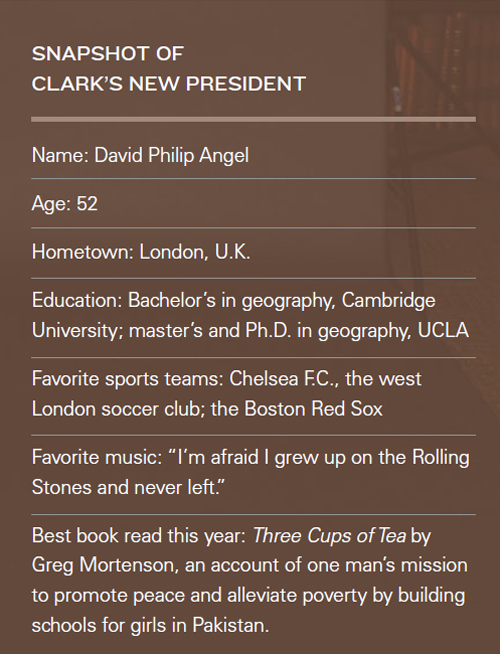

A London native, David Philip Angel brings an interesting mix of attributes to his new job. He is Clark’s first president to come from another country. But at the same time, he has been a long-time fixture on the Clark campus.

Angel arrived at Clark in 1987 as a young geography professor fresh out of UCLA’s geography Ph.D. program. And except for a few visiting professorships, he really has never left Worcester. Along the way, he became Clark’s dean of graduate studies, and then the University’s provost before taking on the presidency in July. A decade ago, he became a U.S. citizen.

Along with his wife, Jocelyne Bauduy, Angel raised his two sons on the city’s West Side during the past two decades.

That Angel possesses both the qualities of an outsider from another land and Clark insider made him particularly appealing to Bill Mosakowski ’76, the chair of Clark’s Board of Trustees and the man who led the effort to find a replacement for outgoing president John Bassett.

Though many universities engage in elaborate external searches to drum up presidential candidates from across the country, “we realized that we had an internal candidate who understood the University really well and had strong support from the faculty and board,” Mosakowski says.

The search for a new president was over soon after it had begun.

As Mosakowski puts it, “David has really distinguished himself in the role of provost. He can articulate the things that Clark needs to do to distinguish ourselves both in the region and nationally, and he has some good thoughts how we can continue to improve our brand internationally.”

Ifrad Islam, a recent Clark graduate who served as president of the undergraduate student body during the last school year, has a similar take on Angel.

“David Angel is a real leader,” says Islam, who was consulted during the presidential selection process. “He’s very well known and liked among the faculty and staff members. He also gets down on the student’s level.”

Clark’s new president started life in Orpington, a town on the southeastern edge of London. His father was a statistician with the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Agriculture. His mother was a homemaker.

Angel has a twin sister and an older sister and brother, all who still reside in England.

A product of Great Britain’s state schooling system, Angel went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in geography from Cambridge in 1980.

“I was interested in issues related to the environment and the natural world and geography provided an interdisciplinary window,” he says.

Upon graduation, he moved to Los Angeles to study for a master’s degree in geography at UCLA. He then went on to receive his Ph.D. in geography. While at UCLA, he met his future wife, who was a graduate student in anthropology.

Angel’s doctoral dissertation, written during the emergence of the high-technology boom in California, focused on the way in which labor markets for Silicon Valley engineers promoted innovation.

Building on this work in the sub-discipline of economic geography, he then studied how innovation in the U.S. semiconductor industry compared with the approaches being pursued by the Japanese and Korean firms.

Once at Clark, Angel decided to take what he had learned about innovation in technologically dynamic industries, such as semiconductors, and apply this knowledge to the issue of greening the economy.

“That is, what types of policies could we use to promote a parallel dynamism around issues of environmental performance improvement and energy efficiency,” he says.

“I became particularly interested in the opportunities for greening in rapidly industrializing economies in Asia and elsewhere. I was an ‘early adopter’ in this work on the greening of industry.”

Reflecting on his early years at the University, Angel lauds the “lively interdisciplinary culture at Clark that had me working with toxicologists, economists, philosophers, and area specialists in a way that is more difficult at larger institutions.”

Angel attributes his ability to make the transition from being a professor to running a university in part to the interdisciplinary mindset that the study of geography fosters.

“My scholarly work has brought me into contact with faculty from across the University,” he says.

As provost, Angel worked to strengthen Clark’s undergraduate programs and to raise the University’s research and graduate profile. His scholarly interest in industrial environmentalism led him to initiate and oversee the university’s Climate Action Plan, which commits Clark to eliminate all campus greenhouse gas emissions over the next 20 years.

urban geography course in the late 1980s.

But Angel knows that in his new job, he will have to win over a far wider audience than students and faculty.

In addition to persuading foundations and corporations to underwrite research initiatives at the University, Clark’s president needs to constantly beat the bushes for additional funds from a 30,000-person alumni network that Angel admits hasn’t been nearly as enthusiastic as it needs to be for Clark to thrive.

A big part of convincing alumni to give more money and support the school with their time is to get them to better understand recent improvements on campus.

“When I talk to most alumni, most of their associations to the school are historic,” he says. “It’s not tied to what we are doing at Clark now.’’

Currently, Angel says, only 18 percent of Clark’s alumni make donations on an annual basis. “If we were to push that number up to 24 percent, that would be a significant accomplishment.”

Moreover, Angel is now entrusted with raising Clark’s profile with college-bound students, so that more students apply to Clark and a greater percentage of those accepted decide to enroll.

On that front, he must contend with Clark’s visibility problem. It doesn’t help, for example, that Clark University doesn’t score well in popular rankings of colleges and universities that are used by high-school students when applying to schools.

According to the latest U.S. News & World Report report ranking of U.S. colleges and universities, Clark ranked 86th among “national universities,” trailing a number of schools that arguably lack Clark’s level of intellectual vitality and academic quality.

In addition, dozens of additional colleges (which lack graduate offerings) are ranked on U.S. News’ separate liberal-arts college list. Thus, it’s easy to understand how a small university like Clark might not appear on the radar of many would-be college and graduate students.

Angel would like to see Clark rise in the rankings, arguing that the school needs to move the needle on several key measures of success that rankers employ, such as the percentage of students graduating from the University within six years, the percentage of accepted applicants attending the university, and even the percentage of alumni contributing money to the school every year.

“We are not going to game the rankings, but if something makes sense for us to do and it helps to make Clark a stronger institution, our rankings will rise in the process,” he says.

Angel wants more students from the U.S. and abroad to apply to Clark, “but more importantly, we would love to see a greater percentage of people who get accepted actually enrolling. We call that ‘yield.’”

Currently, the college’s yield is 20 percent. “If it were 23 percent, it would make an enormous difference. If we get more people accepting us this year, we can afford to be more selective next year.”

Angel seems particularly fixated on the issue of Clark’s graduation rate, which, despite improving sharply under the administration of President John Bassett over the past decade, could be higher. A quality school retains most of its incoming freshman, keeping them from transferring or dropping out.

Under Bassett, says Angel, Clark has improved its graduation rate from 72 percent to 79 percent in the last five or six years. Tufts University, by contrast, is over 90 percent and is ranked 28th on the U.S. News list.

Angel would like to further improve Clark’s graduation rate in the coming years and he thinks he knows how to do it.

“One of the most important contributors to retention and graduation is ensuring students make connections early in their time at college,” Angel says. “These connections can be with a faculty adviser, with a coach, with peer students in clubs and organizations, and with other mentors.”

The goal of retaining more Clark students is also tied to Angel’s boldest initiative in the coming years — the rolling out of “Liberal Education and Effective Practice.”

“In addition to giving a classic liberal arts education, we need to graduate students who have a broader set of capabilities,” says Angel. “I have spoken to folks who have been out of college for three or four years and they hit a roadblock and it knocked them off that path.

“We want to cultivate in our students creativity and resilience” so that they can deal with the challenges of the working world or with graduate or professional education, he says. That’s the “Effective Practice” part of the program.

“If we want juniors and seniors ready to go out into the world, what do we need to do for them in the first year of college to give them a fast start?” he asks. Angel says that Clark will create a short course study-abroad program between freshman and sophomore year as part of LEEP. That experience early in the students’ college education might influence the course of their remaining years at Clark. “If we can empower students to think more broadly about what they are passionate about, and do it early at Clark, then we empower them to take full advantage of the University,” he says.

As Angel markets Clark accomplishments on campus to a wider audience off campus in the coming years, he knows that he will have to deliver a forceful message.

“We spent a lot of time studying institutions that have elevated their reputations,” he says. “One key is that you have to be bold. Higher education is a very noisy marketplace. It’s full of claims. It’s easy to say that you are going to get the very best education by going to College X or University Y, and it’s very challenging for an institution to break through that noise and demonstrate real differential value relative to other institutions.”

David Angel insists he’s prepared to meet that challenge, and maybe even make some noise of his own.

This story was originally published in CLARK Magazine, fall 2010.