Character builder

Leslie (Goldman) Margolis ’96 came to Clark knowing she wanted to be a writer. But her doubts led her down a different path, and into a double major of government and sociology with a minor in women’s studies.

“I couldn’t conceptualize how anyone could survive and support themselves writing fiction so I tried to find something more practical,” she recalls. “Clark is so amazing for social sciences, and I loved all my classes, but then I graduated and all I truly wanted to be was a novelist.”

So, after graduating, she did what every self-respecting prospective author does: move to New York City to work in publishing, be around books and learn how to be a writer. Seven long months later, toiling in the contracts department at Bantam Doubleday (“It was horrible, but it got me to New York!”), she connected with a fellow Clarkie, Valerie Garfield ’92, who was at that time a senior editor at Golden Books.

Garfield helped Margolis secure an interview, and soon she found herself working at Golden Books as an editorial assistant, where she stayed for two and a half years. She did some ghostwriting (contributing to the Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys canons), but there came a day when she wondered if the job was worth it.

“I had plenty of freelance work — ghostwriting mysteries and novelizing movies while also editing at Golden — but I still had my doubts, so I looked for a backup plan and came up with ‘college professor,'” Margolis explains. “I love school and reading and writing so it seemed like a good choice.” She attended the London School of Economics to pursue a master’s degree in social anthropology.

“I studied Latin American revolutions, and it was fascinating. But I quickly realized that being an academic is really challenging, at every single level. If you want to be an academic, you need to dedicate your whole life to that pursuit, which means you should truly be passionate about it. It’s not a good second choice or ‘backup career.’ In fact, it’s a lot like being a novelist and since writing fiction was my true passion, I realized I had to stop avoiding the issue and swallow my fear and really go for it.”

She left London with a master’s degree but no Ph.D. and returned to New York, doing more freelance ghostwriting while working on her own fiction. She finished a novel, which helped her get an agent right away, but it wasn’t until she completed her fourth book, four years later, that she caught the eye of a mainstream publisher — Simon and Schuster — and secured a two-book contract. The resulting works were “Fix” (2006) and “Price of Admission” (2007).

“Since then,” she says, “I’ve been able to sell my original stuff.”

That “stuff” includes two book series for Bloomsbury, a boutique publishing house (and also Harry Potter’s publisher in the U.K.), and a contract with Farrar, Straus and Giroux (a division of Macmillan). The Bloomsbury series are Annabelle Unleashed and The Maggie Brooklyn Mysteries, with books geared toward middle-schoolers (ages 8 to 12).

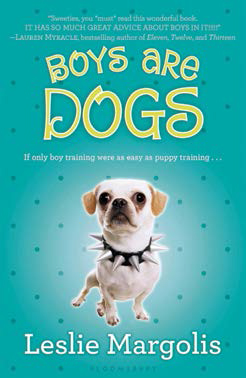

Margolis did not make a conscious decision to write for the ‘tween set, but she had an idea that took off. She thought of a girl who has a hard time dealing with the boys in her life — until she gets a puppy. Training the puppy lets her find her voice and stand up for herself, and she learns “to tame the troublesome boys,” she says.

The resulting book was “Boys Are Dogs,” the first of her Annabelle Unleashed stories, and she thought it fit the middle school age group. The main character, Annabelle, is facing much change in her life — new school, new home — and needs to find a way to deal with it all.

The resulting book was “Boys Are Dogs,” the first of her Annabelle Unleashed stories, and she thought it fit the middle school age group. The main character, Annabelle, is facing much change in her life — new school, new home — and needs to find a way to deal with it all.

When the book was released in 2008, Publisher’s Weekly gave it a starred review and noted that the novel’s premise “has been seen before … but rarely has it been so well grounded and developed.” School Library Journal added more praise: “This clever and humorous premise is deftly handled to create a believable and enjoyable tale with a likable and resourceful heroine whose trials, tribulations, and triumphs will have others wanting a training manual of their own.”

Readers agreed. They loved Annabelle, and Margolis is now working on the fifth book in the series — “Monkey Business.”

She’s also thrilled that “Boys Are Dogs” is being made into a TV movie by The Disney Channel. It will star Zendaya Coleman, one of the channel’s top stars (and a finalist on “Dancing with the Stars”), and is slated to air in 2014. The story has been altered a bit for Hollywood. The main character is named Zoey instead of Annabelle, and the movie is called “Zapped,” but it’s still based on Margolis’ book.

Her other series of novels, the Maggie Brooklyn Mysteries, features a plucky 12-year-old dog walker who solves mysteries around her Brooklyn neighborhood when she’s not dealing with the everyday ups and downs of middle school. Critics lauded the debut of the series, “Girl’s Best Friend,” with Children’s Literature noting that “Maggie is by no means a perfect person, so readers can relate to her and her problems.”

Reader reviews on Barnes & Noble’s website are even more enthusiastic, with several citing “Girl’s Best Friend” as the “best book ever” (punctuated by multiple exclamation points).

“I just love that age group,” Margolis says. Until a year ago, she lived in Brooklyn (in the neighborhood where the Maggie Brooklyn books are set), and she had a focus group of sorts — middle school girls — in her building.

“I would send them drafts of my books, and then I would take them out for pizza and they would critique the stories so I could do a round of rewrites before I sent them to my editor,” she remembers. “These kids always gave me great feedback.”

Sometimes, before writing a story, Margolis will sit with middle-schoolers and ask them questions about their lives. “I guess that’s where my anthropology background comes in,” she laughs.

“I found middle school very traumatic — and fascinating,” she says. “I just think there’s so much drama and emotion, and everything is heightened there.” Margolis acknowledges that her own experiences can seep into her stories. “You’re drawing from real emotions, and that’s what makes your characters authentic and honest.”

The process of writing a book begins with a single concept. “Usually, I come up with an idea and talk to my agent about it,” Margolis says. “If she thinks it’s a good idea, I write up a proposal — about 50 pages, sample chapters — that she sends out to publishers. From there, I get a book contract — or I don’t get a book contract.”

She’ll take between six months to a year to write a draft before shipping it off to her editors. “They’ll say, ‘This is wonderful, I love it — but here are ten pages of notes on how you can make it better.'”

Multiple rounds of rewrites are followed by copyediting and “typeset passes” when Margolis gets to look at the galley proofs. She might make more changes, and there might be additional rounds of edits. “Hopefully, while I’m editing, the publisher is working on a marketing plan, trying to get bloggers and newspapers to write about the book; and my agent is shopping it around, trying to generate interest from Hollywood,” she says. Margolis adds that her 5-year-old son is her best publicist; he makes a point of handing out her books to every older kid he meets. Her 3-year-old daughter isn’t on the marketing team yet.

Once the book is published, Margolis hits the road. “I’ve been on book tours, which are amazing and fun. And I do school visits all over the country — bookstore appearances, too.” Connecting with her readers is her favorite part of the process. “Writing is lonely and isolating, but meeting readers is energizing. The kids are always enthusiastic and they come with great questions: Did this really happen to you? Are you Annabelle? Are you Maggie? Are you famous?”

Margolis also gets a lot of fan mail — mostly email, these days, but some actual letters. “For the most part, I try to answer,” she says. “I think it’s important [to respond] if a kid reaches out to you.”

Margolis was a voracious reader herself in her middle school years. “I really, truly feel that I would not have survived adolescence without fiction. Books saved me. I loved Paula Danzinger, Judy Blume, Beverly Cleary.

“I had to read; I always had a book. I wasn’t always reading great literature, either. I read the Sweet Valley High books too.”

She’s still a reader, but knows that most adults don’t read as much as children. “Right now, I read a novel every week or two, but I was reading twice as many five years ago. I don’t know if it’s because I have little kids now, or that we live in L.A. and I don’t take the subway anymore. There are more things competing for time.”

That’s one reason Margolis doesn’t write for adults. “Luckily, kids still read, and people still think books are good for kids. Children need books, and they need to see other ways of living and being.”

She acknowledges that the publishing industry is suffering, particularly in the realm of adult fiction. “When I graduated in ’96 and went to work in publishing, the industry was in a crisis then,” she says. “People weren’t reading.”

Children’s literature has faced fewer threats, she says, partly because of periodic blasts of energy from sensations like Harry Potter or the Hunger Games trilogy. “Every year there’s something else that comes along; you can never predict it. Following a trend is never what you want to do.”

When she started in publishing, she says, “Everyone had the fear of the looming audiobook. Now it’s the e-book.”

Margolis comes down on the side of the old-fashioned paper book, but insists she’s no activist with this issue. “I try to write the best work I can write, and not get involved in the e-book debate because it’s distracting. I still feel that a good story will find its audience. I just want to focus on being the best writer I can be, and tell the best story I can, and support independent bookstores in every way that I can. That’s challenging enough.”

She adds: “I don’t care how they read it. I just want them to read my book.”

Margolis has fond memories of her days as a Clark undergraduate. She recalls “the friendships and the freedom, and the amazing professors.” She cites professors Cynthia Enloe, Patricia Ewick, and Richard Peet as three of her favorites.

“There was a sense that you could really do anything, study anything,” she says.

When not in class, she wrote for The Scarlet, and was a counselor at the Rape Crisis Center of Central Massachusetts. “I was kind of nerdy and studious, and just really into school, and excited about what I was learning,” she says.

What would she say to Clark students who might harbor a dream to make it as a writer? “It’s hard, but it’s not impossible — a lot of it is about endurance. Don’t give up. It took me four years — and at any point, I could have said, ‘This isn’t working, I’m going to do something else.’ But I didn’t. And here I am.

“If you have a story to tell you will get there.”