Ron Shaich ’76, the founder, chairman and co-CEO of Panera Bread, is a contrarian. Rather than follow the pack, Shaich is a true entrepreneur who spends his life creating unique solutions for problems he sees in the world. Take Panera Cares, an initiative Shaich launched out of the Panera Bread Foundation in 2010. These nonprofit community cafés seek to address the growing problem of food insecurity in the United States by committing to feed with dignity each and every person who walks through the doors regardless of their means. Creating the first national chain of “pay-what-you-can” cafés is most certainly a contrarian approach … and Shaich would have it no other way.

Read more about Ron Shaich in a recent Washington Post article.

Each year, through various charitable programs, Panera gives away $50 to $100 million worth of product and cash to various nonprofits across the country. These are big numbers. And yet, despite the fact that these contributions are not insignificant, I have long found this type of giving to be inauthentic. Why? Because we’re disconnected from it. The product goes out the back door in a black plastic bag to a food pantry or soup kitchen. We don’t serve it. We don’t interact with the people on the other end who are eating it. Same goes for the money. We write a check to an organization and then hand it off, allowing them to decide how to use the funds.

A few years ago, I challenged myself to figure out another way Panera could do it. How do we do something that’s more connected with our own arms and legs, our own bodies? In other words, how do we use our core competencies and our own people to make a direct and real difference in the communities in which we operate?

When we first embarked on this social experiment we now call Panera Cares, it was all about learning. We didn’t know what it would look like. We knew that we wanted our experience to enhance, to uplift, to offer dignity, and we worked out the details along the way. I originally thought we would open places that offered baked goods and some coffee at discounted rates. Soon, however, we began to realize that, if we were going to put the Panera name on this and attract customers by creating environments that brought them together, we had to put the full Panera menu out there — the full-bore Panera experience. It was going to be Panera without price tags and cash registers. Instead, we would have suggested donation amounts and donation bins.

There is always a moment of truth and, in any adventure, you don’t know what’s going to happen until you do it. We jumped off that high diving board on May 16, 2010, with the opening of the first Panera Cares Community Café in Clayton, Missouri.

So many people think that the hard work is done once you open your doors. That’s exactly wrong. Our grand opening was only the beginning. We were playing with a prototype. We had a hypothesis. We had to see how the concept actually took form and then create solutions as we went along. So I did what every entrepreneur does — I got in there and tried to figure it out myself. What works? What doesn’t? I spent three weeks in that café, working 100 hours a week to see what it was and how it danced — and I loved it. Many of our team members were scared about what would happen if this experience didn’t work. Would they lose their jobs? Where would people struggling with food insecurity eat? Some of our own associates had dealt with hunger before and were able to relate to many of our customers in a tangible way. They looked at us and said, “We’ve got to make this work.”

I remember my biggest battle in those first couple of weeks was getting our associates to relinquish their judgments. You’d have a customer walk in and say, “I’ll take forty dollars’ worth of sandwiches — and put three dollars on daddy’s Bank of America card.” If I was working behind the counter when that happened, I’d want to jump across and kill the kid. How do you think our associates felt? The real challenge to us was to try and tone them down; to protect the concept and be free.

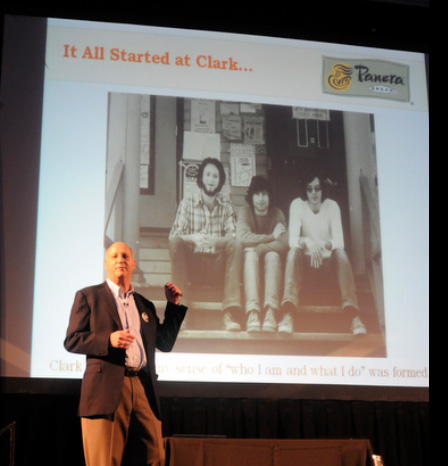

Ron Shaich at Reunion 2011: It all started with Clark’s General Store

There was a 75-year-old woman named Miss Beth, who has worked at Panera for many years. On opening day, she said to me, “Ron, I just want you to know something. I’ve experienced pain in my life, I’ve been there; I know we need this very badly. I went to church this morning and prayed for this place.” I understood how much these folks needed this to work for themselves as well, and I didn’t want to let them down.

So, two-plus years later, is it working? The answer is “yes.” One of every five people leaves more than the suggested donation amount, with no pressure on them. Three of five leave the suggested donation, and one in five leaves less, usually significantly less or nothing because they have real need. What’s most amazing to me is how the concept has really caught on. People get it. They talk about it, they feel it, they support it. In addition to our original Clayton site, we now operate three additional community cafés in Dearborn, Mich., Portland, Ore., and Chicago.

Panera Cares Community Cafés are committed to providing a dignified experience for all. This is about sharing, about community, about shared responsibility. This is not about treating those in need as separate from us. It’s about stepping up and committing to help one another based on the understanding that, at one time or another, all of us will need a hand up of some sort.

Many people often ask me if this is “a business model.” My answer is a quick “no.” This is a model based on shared responsibility that we actively try to encourage within our communities. The fundamental reason this can work is people trust us. They trust us because we are completely transparent — there are no games being played, there is no alternative motive other than literally trying to do what we say we’re going to do.

For me, Panera Cares has been proof positive that humanity is fundamentally good. Give people the chance and most will do the right thing. Not everybody — there are bad people out there who will take advantage. But the key to building community and building our society is to focus our concept on the people who are good, who do step up, and not be driven down by those who don’t.

We in corporate America have a responsibility that’s broader than our profit and our earnings next quarter. We have a responsibility to use our core competencies to make a real difference in the communities that have enabled our business success in the first place. We have that responsibility because we share this society and carry a collective burden to leave it better than we found it. This is about all of us.

(From CLARK Magazine, fall 2012)

Read Ron’s speech at Commencement 2014