John M. Johansen considered the audience seated before him inside the Robert Hutchings Goddard Library’s Rare Book Room, and offered a humble assessment of the building he designed 43 years ago. “Architects think of their most recent work as being their best,” he said. “But they can come back to earlier work and they say, ‘Not bad.’”

Johansen, 96, returned to Clark University on March 14 to help launch the exhibition, “The Life of a Campus: Clark Buildings Then & Now, 1887-2012,” created by the students of Kristina Wilson, associate professor of art history. The exhibition traces the evolution of Clark architecture from its first building, Jonas Clark Hall, through the campus’ gothic and modernist periods, and concludes with the University’s “green construction” exemplified by the Lasry Center for Bioscience and Blackstone Hall. But this day, the standing-room-only crowd of about 75 people had come to hear about the Goddard Library from the lips of the man who gave it form.

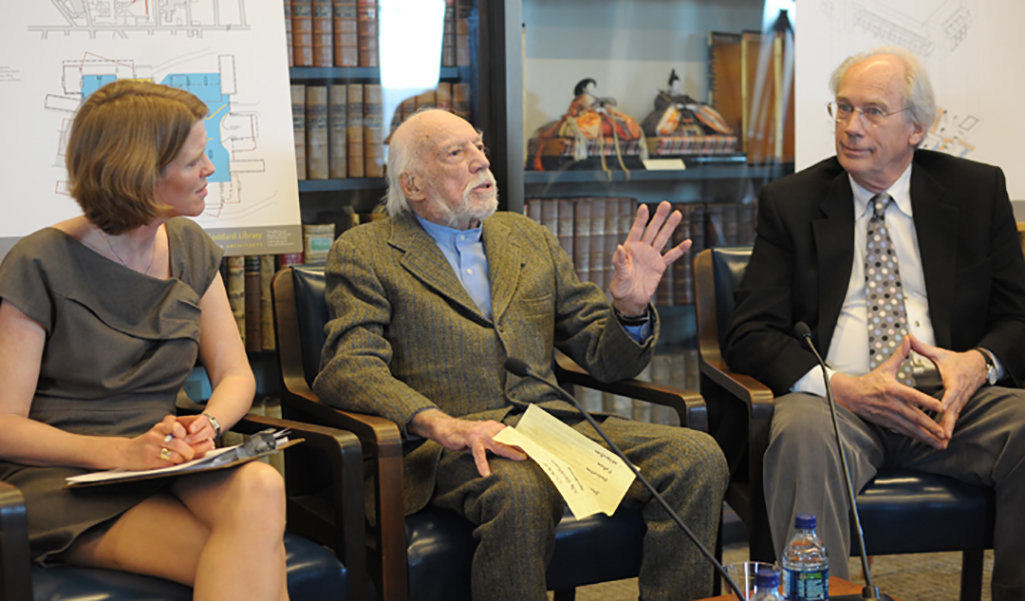

The building remains an enduring example of “brutalist” architecture, an innovative, forward-thinking style that perhaps reflects Johansen’s recollection of “being full of ideas — possible and impossible.” Johansen was joined by architects Steven Foote and Mark Freeman, who in 2009 augmented the original building by creating the Academic Commons. Wilson moderated the discussion.

Johansen began the presentation by insisting he doesn’t know why Clark selected him to design the new library — among others under early consideration were architectural luminaries I.M. Pei and Louis Kahn — but recalled that when he was being interviewed by the selection committee he spied on the wall a portrait of a former Clark president that had been painted by his father. “That did me no harm,” he quipped.

To arrive at the library’s ultimate design, Johansen said he served as a combination architect and psychoanalyst, listening intensely to the suggestions of Clark’s trustees and administrators, then helping them shape the “cluster of ideas” and incorporate them into his vision for the building. “No building has ever been considered important without considering the client,” he said. “It takes a good client to do a good building.”

Any edifice, Johansen noted, is the culmination of the site, the client, the budget and the materials, but he cautioned “don’t make too much or too little of the creative process … in short, I would call it orchestrating.” For an architect, the process of adding a building to the landscape truly begins “when you cut the connection to your ego.”

Johansen ascribed living characteristics to the library, comparing it to an organism that breathes and grows, and is equipped with its own unique DNA. Though it was highly planned, the building carries with it a sense of the chaotic, the eccentric, or as Johansen termed it: anti-composition. “[It’s] an assemblage, an accretion of functions; not a building, not fine art, no pretensions. Let it happen.”

He illustrated his philosophy by quoting an old friend, also an architect, who told him, “Buildings develop a will of their own and tell you how they want to be finished.”

If Jonas Clark Hall is Clark’s iconic building, the library is its most whimsical. Johansen peppered his descriptions of the Goddard space with phrases like “a little bit of poetry,” and “space playing.” “It should be fun,” he said. “So many architects are too serious — I was a wild man at that time, and still believe I am.”

Johansen noted that one of his goals had been to preserve the site’s “confluence of paths” that were once trodden by the Mohegan tribe more than a century before Clark students walked that same ground, so the library was elevated one level to allow passage below the building. “

Foote said the form and function of the Academic Commons were inevitable — designed to accommodate new modes of learning, which are more collaborative and more social in nature than they were in the days when librarians shushed students among the stacks. Libraries, he said, have evolved “from places where knowledge is stored to places where knowledge is created.”

The Academic Commons is essentially the “college living room,” Foote said, a comfortable, casual space with plenty of sofas on which to sprawl and coffee just a short walk away across a carpeted floor.

Initially, the AC was to be located on the first floor of the library, but was relocated to the plaza level, where the “crossroads” — the network of paths — was eventually enclosed, creating 11,000 square feet of new space. Freeman said the “sculptural quality” of Johansen’s building offered a wide range of possibilities for the commons. He noted that library’s ceilings are particularly distinctive because they have no continuous flat planes, which allows for a stylish interior space that’s just as “exciting” as the exterior.

“There was a conversation about how we [could] mess with this building, which is a very strong standalone statement,” Freeman said. The key was not to try and create the new space as a clone of Johansen’s structure, yet to be sure that it remained “sympathetic” with the original building’s bold look that was so revolutionary for its time it attracted national scrutiny and brought out astronaut Buzz Aldrin to cut the ribbon at the May 19, 1969 opening.

Foote recalled that the trustees were concerned when they heard about “these new architects who were going to tinker with the masterwork.” A smiling Johansen then piped up, “You wouldn’t dare,” drawing laughter from the audience.

Johansen, who was seeing the Academic Commons for the first time since its construction, praised the space as a “wonderful” alteration, and noted that, while he respects history, it’s the promise of the future that sustains him. “This building is 43 years old,” he said. “That’s young, isn’t it? I hope it’s here some time longer.”