Clark Magazine

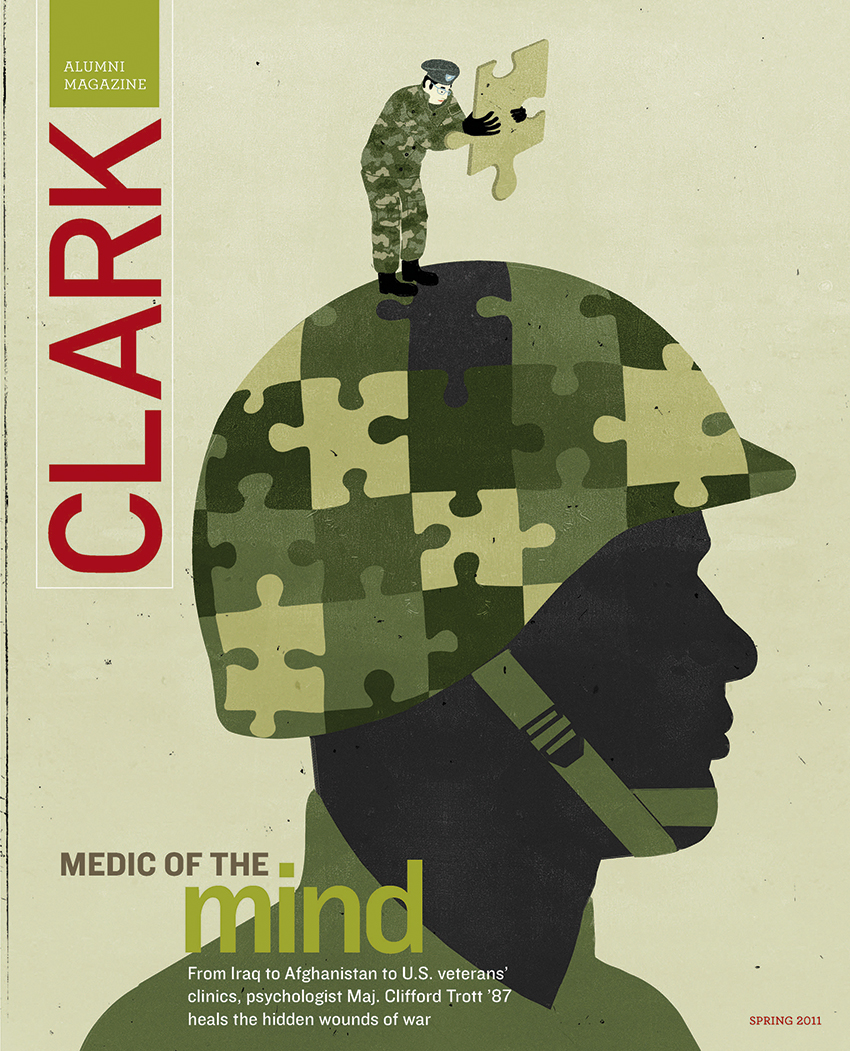

Medic of the mind

When you’re a soldier serving in Iraq or Afghanistan, danger is a constant companion.

Mortar fire and roadside bombs, landmines and sniper fire can inflict anything from a light wound to life-changing devastation. You may worry that you’ll give in to the fear that nags at you, that you’ll inadvertently let your buddies down in a crisis.

In the quieter hours when you want to sleep but can’t, other concerns that hover in the back of your mind can creep to the fore — your kid’s troubling report card, your spouse’s job security, the leaking roof at home.

Then there’s the shock of being in an alien culture and climate, of not knowing whom you can trust among the local population. Anxiety is compounded by physical discomforts — the weight of equipment you tote in the heat, the irregular eating and sleeping hours, the lack of privacy. It all adds up to a lot of stress, and readily available psychological support may be the key to ensuring that you have the resilience to stay in the fray, and to transition successfully back to civilian life.

Enter Dr. Clifford Trott ’87, a thoughtful, soft-spoken man who has chosen to spend time in some of the most perilous places on earth. In 2002, this self-described “Clarkie liberal,” who had had no previous military aspirations, enlisted as a clinical psychologist with the U.S. Army Reserve. Since then, he has been deployed to both Iraq and Afghanistan, and now retains his commission as a major with the Vermont National Guard. He has come to learn the workings of the soldier’s mind and has devoted his career to treating men and women for whom, even after the shooting has stopped, the battle still rages.

Time to give back

On a bleak November day, over coffee and chili in a Burlington, Vt., café, Trott reveals what prompted him to turn his almost too-good-to-be-true life on end and head into harm’s way. “I had a pretty nice life,” he admits.

“I grew up on a beautiful island, I went to this great school, I loved what I was doing for work. I had a great group of friends, a wonderful, supportive family and a thriving private practice. And I thought, ‘There’s going to be time to give back.'”

Trott, a native of Nantucket who could be a convincing model for the L.L. Bean catalogue, wanted to use his professional skills to do something “bigger and more global” than volunteer in his local community. And, as a new homeowner, he was looking for a way to make a difference and still pay the mortgage. Then an opportunity presented itself in an unexpected place.

As Trott was exploring his options, he chanced on a profile in a magazine about the typical armed forces member. The article noted that many recruits were economically disadvantaged and often came from rural areas. They weren’t joining to kill people, but rather to take advantage of the vocational and educational opportunities that serving their country would provide. That characterization struck a chord.

“This was a disenfranchised population,” he says. “I wanted to bring my craft to people who needed that kind of help. I thought about it for a while and decided to raise my right hand, take the oath and join [the Army Reserve].”

Trott describes his entry into the Reserve as “a cultural education.” He readily admits that his stereotypes of military life clashed with many of his personal values. Nor did he have any idea what a military psychologist actually did. But he decided to take a chance on serving a group of people who resonated with him.

“It was a huge leap of faith to join this organization,” he explains. “The political infrastructure I’d either deal with or not, and I wouldn’t have to stay if it was a bad fit. I could always get out in a couple of years. That was my game plan.”

Boundaries blurred

Engaging with out-of-the-mainstream and economically marginalized populations was nothing new for Trott. In addition to growing up in a family embedded for generations on a small island, the Clark psychology grad had spent time in rural areas while completing his Ph.D. at the University of South Dakota, and later served two years as a clinical psychologist in the town of Canaan, located near the Canadian border in Vermont’s remote Northeast Kingdom. Officially he was employed as the child and adolescent psychologist at the K-12 public school, but as the only mental health professional in the entire county, Trott soon realized that — unofficially anyway — his clients would not be limited to the school-aged population.

Engaging with out-of-the-mainstream and economically marginalized populations was nothing new for Trott. In addition to growing up in a family embedded for generations on a small island, the Clark psychology grad had spent time in rural areas while completing his Ph.D. at the University of South Dakota, and later served two years as a clinical psychologist in the town of Canaan, located near the Canadian border in Vermont’s remote Northeast Kingdom. Officially he was employed as the child and adolescent psychologist at the K-12 public school, but as the only mental health professional in the entire county, Trott soon realized that — unofficially anyway — his clients would not be limited to the school-aged population.

“In addition to children,” he recalls, “I was working with their families, and essentially anyone the town needed me to see. There were random situations, like the transient man whom nobody knew who was clearly having a psychotic episode. There was no mental health support out there at all.”

Having previously enjoyed a stint working at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., and volunteering at the American Psychological Association, moving to Canaan took some adjustment, in part because of the dearth of professional colleagues. Nonetheless, there were compensations.

“To be in a place where you’re the only one in your field — it was a big transition,” he says. “But after a while I settled in and started to appreciate the beauty and nature, the humbleness and authenticity of the people who lived there. There were a lot of farm families that I worked with. They were living in poverty and were too proud to let [the farm] go. It was painful to see.”

And in a community where self-sufficiency is prized, many were uncomfortable asking for help with mental health issues. That was an obstacle Trott would later encounter in his military service.

Another challenge Trott grappled with in Canaan was the almost unavoidable blurring of personal and professional boundaries. As a psychologist, he must remain objective in order to be therapeutically effective with his clients. Those clients need to trust that the problems they confide will remain confidential. But chance encounters with patients outside the office made boundary-setting difficult, one of the reasons why, despite his roots in Nantucket, he has resisted offers to practice there.

“I’d love it, but because it’s an island, interaction happens very intensely,” he says. “You run into everyone at the libraries, store, school. Having grown up there and knowing all kinds of stuff, I think it would be a little challenging to be the psychologist who’s the ‘keeper of secrets.’ It was very challenging in Canaan. I’m all about boundaries.”

‘The wizard’ of war

The nature of the job demands that soldiers be physically and mentally tough in the most adverse conditions. Only recently has the very real psychological damage that can result from serving in a war zone been publicly acknowledged. Combat Stress Control Detachments staffed by psychology professionals and technicians are now positioned with the soldiers close to the action, within reach of officers and enlisted men and women who might need help navigating the potential emotional hazards that accompany war. Once known as shell shock or battle fatigue, combat stress reaction is now officially recognized as a normal response to an abnormal situation, and detachment members provide education about and evaluation of related symptoms.

As one of these medics of the mind, Trott deployed first to Iraq in 2004 with the 1908th Combat Stress Control Detachment, and later to Afghanistan. The detachment consisted of approximately fifty psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, mental health technicians, occupational therapists and assistants who served soldiers in Iraq’s Ramadi area. Trott, accompanied by several mental health technicians, would travel to wherever he was needed.

As part of the detachment, Trott found himself serving yet another isolated and tightly knit population. Lessons learned in Canaan stood him in good stead.

Although the services Trott provided were officially sanctioned, the stigma attached to requesting mental health support had not been eradicated. Many service members worried that such a request would jeopardize their careers.

Trott believes that a military unit’s commanding officer is key to creating a culture where soldiers feel it’s okay to ask for help, and cites the example of a commander who openly and regularly stopped by another psychologist’s office for a cup of coffee. The commander explained it to Trott this way: “My soldiers watch everything I do. If they see I’m coming in here and closing the door a couple times a week, they’re going to have decreased negative perception about coming in here [themselves]. I want them to feel comfortable to come in and talk to you.”

But Trott found other officers, notably those in aviation units, were less receptive, in part because a psychologist has the authority to ground an air crew. Trott, who completed training in aviation psychology between his Iraq and Afghanistan deployments, describes one such lieutenant, and his later change of heart.

But Trott found other officers, notably those in aviation units, were less receptive, in part because a psychologist has the authority to ground an air crew. Trott, who completed training in aviation psychology between his Iraq and Afghanistan deployments, describes one such lieutenant, and his later change of heart.

“I would stop over every day, just kind of check on him,” Trott recalls, noting that the lieutenant was initially unreceptive to his outreach efforts. “One morning at about 3 a.m the lieutenant came rapping on my door, and said, ‘I need you, I need you right now.’ One of the airmen had had a really rough mission. I stayed with the soldier for about two and a half hours, just helping him sort it all out. From that point on, that lieutenant flew me wherever I wanted to go.”

Reaction to Trott’s role could be mixed. At one point he learned that some Marines were referring to him as “The Wizard.” Although puzzled, he decided to take it as a compliment, assuming the nickname was a tribute to his professional skills.

But then a corpsman provided a more ominous explanation.

“Cause you can make people disappear, sir,” the man told Trott. “Sometimes soldiers go to the psychologist and then they magically disappear.”

‘A rare breed of psychologist’

As a member of the detachment, Trott partook of the same eating, sleeping, and recreational arrangements as his clients. He also shared the danger, whether it was riding in a convoy or being on a base that was under attack. He was never “off the clock,” because the call for his services could come at any time or place. At the gym or the chow hall, soldiers would approach him, wanting to talk. As a result, just like in Canaan, boundaries were difficult to maintain.

Trott’s habit is to engage in self-comfort practices throughout the day, such as listening to music, yoga and meditation, techniques that he says “quiet your soul and recharge your batteries.” The challenge came when circumstances didn’t accommodate those niceties, and soldiers expected Trott to set an example of how to stay cool under fire.

“They’d ask quite pointed questions like, ‘How are you dealing with it?'” he recalls. “Sometimes that’s nice, because it shares a level of personal connection and authenticity. But you also don’t have that nice little bubble that can be needed for objectivity. It’s a nice compliment that they feel comfortable about coming up and talking about whatever is going on, but you don’t have a break.”

Trott and his team were proactive, reaching out to the units in their care on a daily basis and checking in with commanders to see how things were going. That kind of rapport-building is critical if soldiers in a crisis situation need help fast. Trott’s team would learn from the commanders what a unit had been experiencing over the past couple of days. In return, his team educated commanders about how to spot the signs and symptoms of serious psychological distress.

For two months psychologist Col. Kathy Platoni worked closely with Trott at Camp Phoenix in Kabul, Afghanistan. She characterizes him as “a rare breed of psychologist — the best of the best, both clinically and ethically. In some of the most austere and limiting conditions, he was able to create a full-fledged clinic for the 22,000 soldiers in his area. [He was] loved, admired and respected by everyone.”

Lt. Denis Consolver, an infantry veteran of the first Gulf War, served in 2004 as a mental health technician with Trott’s team in Iraq. His task, as he describes it, was “to get these clinicians ready for the harshness of military life in a war zone.” As the non-commissioned officer-in-charge, Consolver was impressed with Trott’s honesty and willingness to take direction from someone he outranked.

“Trott had no problem letting me tell him what needed to be done and how to do it, based on my 16 years’ experience,” Consolver writes via e-mail. “Many other officers would rather drive into a mine field than listen to an enlisted soldier.”

Consolver describes Trott as someone “who will go way beyond expectations to see that someone is taken care of.” (He also appreciated Trott’s generosity in sharing the Vermont coffee he received periodically in the mail.)

Bombs and breakfast

Between stints in Iraq and Afghanistan, Trott returned to D.C. to work at National Guard Bureau Headquarters, and also provided some outreach through the Colchester, Vt., Veterans Administration clinic just north of Burlington. As of January, Trott has returned to work there fulltime. He can still be deployed, but because of a troubling ethical situation that arose when he was in Afghanistan, he’s not sure whether he wants to stay in the Guard.

A superior officer pressured him to divulge patient information, the confidentiality of which is protected under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Trott refused, and tried contacting the medical Judge Advocate General, but the situation only worsened. He came away disillusioned.

“It really surprised me that folks would practice unethically and not be respectful of laws and regulations,” he says. “I know that sounds terribly naïve, but I thought medical folks were different, particularly when it came to patient rights and privacy. That was an eye-opening experience, to say the least.”

Trott explains that HIPAA protection applies to military personnel as well as civilians. “However, sometimes commanders try to get around it, use their rank. If you don’t give them what they want, they can get nasty.”

Trott seems more troubled by that experience than any of the physical danger he was exposed to during his deployments. When asked whether he ever feared for his life, he understates the risks.

“Did I feel my life was in danger?” He thinks for a minute. “No. But Iraq was a bit hairier than Afghanistan. In Afghanistan bases would get bombed every now and then, but it wasn’t a big deal. In Iraq the bases were smaller and people were getting killed.”

Trott describes the emotional transition he underwent during deployment, and how something that was first perceived as life-threatening becomes relegated to the status of irritant.

“One morning I was in the chow hall having breakfast. I’d just gotten my food, and then the whole building shook. But I’m thinking, ‘I just want to frickin’ eat!’ The first couple times [it happens] you’re like ‘God, I could be killed.’ Then it becomes, ‘I’ve got my Raisin Bran here, let me eat it.’ The gal in the bunker with me was kind of freaking out, and so I was doing some relaxation training with her, and we got laughing about the inconvenience. Then I wondered, how did I get to a point of ‘Here we go again,’ and disconnecting from this event that could take my life? It’s habituation. ”

On one base we would get mortar fire quite a bit. Occasionally someone would drop their weapon — it happens sometimes and makes quite a racket. Just that noise [would occur] and several folks would hit the deck. And then they’d laugh about it. So the initial startle is still there, but it’s followed by, ‘Oh, okay, it’s just a weapon.'”

Transitioning to civilian life

The hyperawareness that can save a soldier’s life in a war zone can become a handicap in civilian life.

For some vets, a loud bang at a Fourth of July celebration can result in a flashback-like reaction. While such a response will eventually diminish for most, for others the process may require treatment to help them gain control of their responses, Trott says.

Even Trott, whose job is to educate soldiers about what to expect when re-acclimating to civilian life, was not immune to the emotional roller coaster.

“The transition from war zone back to civilian life is necessarily difficult. When I got back from Iraq in 2005, I was not prepared. I thought, ‘I’m a psychologist, I’ve got it covered.’ But I got back, and I struggled. I struggled.”

When friends noticed he seemed to be having problems adjusting, Trott got himself some therapy. ”

After I returned from Afghanistan I went to an ashram in Quebec for a week. You know how infants are colicky and fussy and nothing will calm them? I sort of felt like that for the first two days. I didn’t want to be there, and it brought up stuff that had to be dealt with, and I didn’t want to deal with it. Many times I thought about just hopping in my car and driving back to Burlington.”

Assimilating to the civilian world can be especially difficult for National Guard and Reserve personnel because those soldiers are more integrated into a civilian area than are active duty soldiers living on bases. Returning soldiers often carry unresolved emotional issues that can have a big impact on a small community. The ripple effect reaches into many aspects of life.

“When service members come back and they’re struggling, the community hasn’t received a lot of education about what to expect,” Trott says. “All they know is they were gone for a series of months or a year, and now they’re different. They’re left with a lot of questions, and not a lot of answers. That’s a shortcoming that the Guard and Reserve are really trying to fix — some would argue not too well.”

The Clark fit

Trott credits Clark with playing a critical role in his development from a “very shy and introverted” teenager to feeling that he could be himself and be accepted.

“When I got to Clark, I just shed that skin — left it on Nantucket. I became more social, comfortable in my own skin. I think the Clark community afforded that development in a nice way. I started to realize that I can fit wherever I want. There was so much support and encouragement — more ‘can do’ than ‘can’t do.’ That’s a really important lesson for a kid from a very sheltered island.”

He’s also full of praise for the academic nurturing he received as a budding psychologist. In fact, it was his early interest in psychology, combined with Clark’s reputation in that field, that led him to apply. He started doing research in developmental psychology during his sophomore year under the guidance of the late Dr. Ina Uzgiris.

“She was a great adviser for me to have,” he says. “She had worked with Piaget! I’m in developmental psychology class, watching old black and white videos of Jean Piaget, and there’s Dr. Uzgiris setting up the blocks! To have an adviser who’d worked with The Man; just to have that kind of support and individualized attention. If I had gone somewhere like UMass, I doubt I would have gone on to grad school.”

Hope for healing

The media are full of stories about the psychological damage many soldiers are sustaining during deployment, serious conditions such as severe depression, traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder. Trott reports that progress is being made in helping soldiers heal from combat-induced psychological injury. He has seen the research first hand, both when he worked in Washington, D.C., overseeing and coordinating all of the state National Guard psychological services, and when he headed up the post-traumatic stress disorder treatment program at the Veterans Administration clinic in Cleveland, Ohio.

Trott is proud of his eight years of military service.

“It’s inherently rewarding to be a psychologist; working with a population that can be in such dire need makes it that much more rewarding,” he says. “Many times in Afghanistan and Iraq, people would pull me aside and say, ‘Your job must be so stressful.’ It is stressful, but it also has that level of reward that other professions don’t have.

“I think I don’t take things for granted as much. I’m more grateful for what I have, for friends and family, and more keenly aware of how good my life is and what my blind spots are. I don’t get broadsided as quickly by life.”

Editor’s note: This story was originally published in Clark Alumni Magazine, spring 2011.