Floyd Ramsdell: The ‘Goddard of 3D’

Excerpted from “Changing the World: Clark University’s Pioneering People, 1887–2000” (Chandler House Press, 2005), by former president Richard P. Traina.

Floyd Abner Ramsdell deserves to be more widely known than he is. There is much more to be discovered about him in archives, museums, law offices, and family and acquaintance memories. We do know that, among those who were familiar with the field of film production during his life, he was widely recognized as a pioneer in the development of three-dimensional film. One can only surmise that the reason he is not more widely known and appreciated today was that he lacked the particular ambition or disposition required of him. He was far more caught up in ideas and invention than he was adept in public relations and self-promotion.

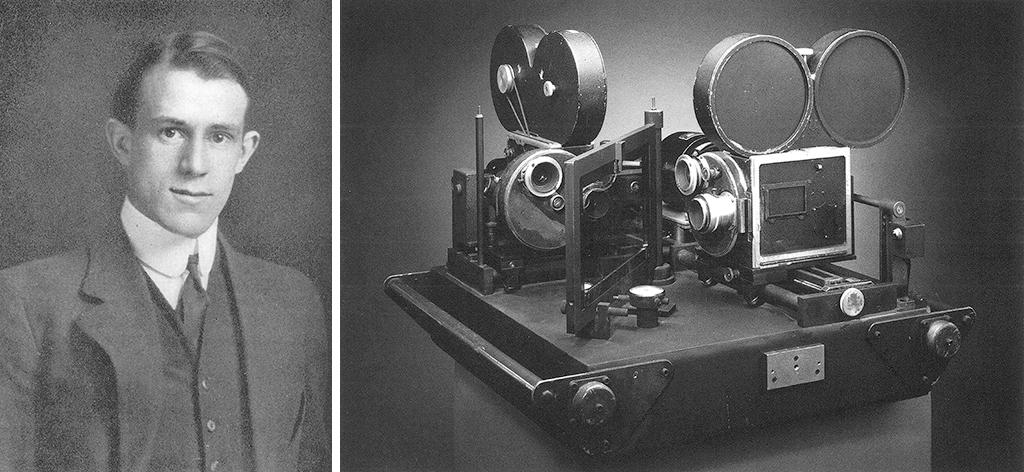

Ramsdell was a Worcester native and attended the undergraduate college at Clark University in its earliest years, when the distinguished Carroll Wright was the undergraduate college’s president. This was the era of the three-year baccalaureate degree at Clark, and Ramsdell received his in 1910 at the age of 19. Indicative of the direction his life would take, he sold stereopticons to earn money for college. The Clark yearbook for his graduating class teasingly reported that he had once petitioned the faculty for a new major in gym and recreation, “so that future students may not be handicapped with lessons while in college.” It also remarked that “Skid” (his nickname signifying “all speed and no control’) “has taken in all sides of college life.” In truth, whatever else he might have been, Ramsdell was a talented gymnast, a wilderness guide, a skilled archer, and an inveterate fisherman. (Later in life, he would be up at 4:30 in the morning to go back and forth between lake and kitchen, catching fish and eating three breakfasts-the last one, a jelly doughnut crowned with still more jelly.) Academics must not have passed him by completely at Clark, as his long career was to be marked by a particular brilliance in physics and mathematics, especially geometry, as applied to moving pictures.

Following some years as a high-school geometry teacher, Ramsdell established in 1918 the Worcester Film Corporation — a rather pioneering act in itself at that time. Local investors Weld Morgan and Linwood Erskine provided the primary start-up funds and named Ramsdell general manager. Out of that company, he made a career of producing medical, industrial, technical and educational films. He also became interested in the potential and the technological challenges of producing three-dimensional films.

Learning of Ramsdell’s interests and competence, Edwin Land invited the Worcester filmmaker during the 1930s to experiment with his Polaroid Corporation’s new prismatic “beam splitter” toward the goal of producing effective three-dimensional film. Ramsdell used Land’s polarizing plastic to separate the right and left eye images recorded by two cameras through the beam splitter. The first known public showing of a Ramsdell 3-D film occurred at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in June 1937, at a meeting of the school’s alumni — each person outfitted with a pair of Polaroid glasses to achieve the three-dimensional effect. While impressive, the film did not please Ramsdell, who was bothered by the distortion in dose-ups. This was a classic problem in geometry.

The geometry of 3-D film posed an incredible challenge. It involved the use of two side-by-side synchronized cameras filming from slightly different angles, all the time affected by the distance from the subject, which, of course, was moving. The depth had to be proportionate to the height and the width, or else distortion would confound viewing. When it came to showing the film, there were the tangled factors of two synchronized projectors, their distance from each other and from the screen, and the size of the screen.

While Ramsdell worked on the mathematics of this complex set of problems, he continued to turn out three-dimensional films, producing one in 1939 that eliminated serious dose-up distortion, and in the following year producing at least two in color. One was a film for the Norton Company, a major producer of abrasives. When Ramsdell filmed the grinding machines at work, it was said that “every piston, bar, cam, or moving part appeared to stand out in space.” The other color film in 1940 was of his daughter piloting a speedboat on Lake Winnipesaukee. One journalist wrote that “watching Barbara pilot this boat [at 30 miles per hour] and viewing the landscape as it passed is an exciting experience. You get the feeling that you can reach out and touch the water…. It’s a new sensation.”

It was not until after World War II that commercial development of 3-D films attracted Hollywood. The diminishing attendance at American movie theatres, partly due to the arrival of television, prompted interest in the “next film revolution,” from silents to “talkies” to three-dimensions. A number of 3-D film inventors tried their particular theories — J.A. Norling, Frank A. Weber, Raymond Spottiswoode, and Semyon Ivanov among them. During the 1950s, films like “Bwana, Devil,” “Man in the Dark,” and “House of Wax” drew large audiences and much controversy. The Christian Science Monitor commented for example: “Watching ‘House of Wax’ is rather like spending an hour and a half on the rack. One comes away feeling physically assaulted and numbed.” But it was not simply the attempt by filmmakers to frighten the audience, with lions landing in viewers’ laps or fires pouring from the screen; it was the effect on many people of the Polaroid lenses they had to wear and widespread complaints of headaches.

Hollywood continued to produce three-dimensional movies; Columbia Pictures, as one example, produced at least ten of them. Ramsdell was called to Hollywood by Metro Goldwyn Mayer, the eventual producer of a couple of 3-D movies, including “Kiss Me, Kate.” The experience disillusioned Ramsdell. The technical people in Hollywood knew nothing, he felt, about the mathematics of three-dimensional filmmaking and projecting — and he was inclined to let them know that. He described them as not even understanding the need to change the location of the cameras or what happens when you preview a film on an eight-foot screen in the studio and then project it onto a 40-foot screen in a movie theatre. Late in his life, he typed a letter to Clark University’s first professor of film studies, Anthony Hodgkinson: “Probably those dummies out in Hollywood didn’t know a thing about geomettry [sic].” And the then-90-year-old added, teasing himself: “There seems to be evidence that I don’t know much about spelling.”

Ramsdell wrote at least two articles on the complex physics and mathematics of “stereo film,” perhaps the better of them being “The Mathematics Involved in Three Dimensional Photography.” Standish Lawder, a Yale film scholar with a special interest in 3-D movies, wrote to Ramsdell about these articles: “They represent the most lucid description of stereo geometry that I have found.” And, “of the many people and sources I have consulted … none have had the depth and detail of understanding which you possess.”

To the end of his long life, Ramsdell remained a remarkable figure. On account of his devil-may-care haste, his hands were a mess — every finger was clipped, scarred, or missing its tip. He just did not take the time to be safe — even climbing a ladder onto a roof in his eighties. His mental acuity stayed with him: In his nineties, he could quickly look through a deck of cards a few times, turn them face down, and recall the order. He combined an uncommon visual memory with mnemonic tricks and, of course, he had always had an astonishingly acute and intuitive mathematical sense.

Throughout his professional career, whatever the project, Ramsdell’s resourcefulness and sense of humor found ways to surface. Once, filming “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” he faced the problem of trying to get a real lamb to follow the costumed Mary. He solved it, with a smile, by concealing the young lamb’s bottle under Mary’s ample skirts.

In 1947, there was an article in Life magazine involving Ramsdell, featuring a remarkable first-time achievement while he was working with a medical scientist from Johns Hopkins University: He filmed the digestive tract of a live dog by inserting a tube and camera he had invented. When subsequently asked about this project, Ramsdell said that they were able to see “a dog belching — from the inside.” With respect to his accomplishments, he typically displayed a calculated “sense of proportion.” Given that he was a 3-D film pioneer and given where the medical world has since gone with filming and exploring the interiors of humans, there is no little irony in his sometimes self-effacing characterizations of his accomplishments.

During his career, Ramsdell produced a wide array of three-dimensional film patents that long ago expired. (One can, however, view his 3-D cameras and lenses at the American Museum of the Moving Image, in Astoria, New York, across the 59th Street Bridge from Manhattan.) Three-dimensional film is only now beginning to have a resurgence, particularly in museum theaters. It has not yet found its marriage between mathematically trained technicians and inspired commercial film artists. The aesthetic potential of three-dimensional dramatic film awaits its artistic developer. When that happens, perhaps Ramsdell will be rediscovered in something like the terms used years ago by a Polaroid executive, as “the Robert H. Goddard of 3-D.”